At first glance, the geniuses of history and present deserve the pedestals that society places them on. For some, their favourite contemporary greats such as Beyoncé or Taylor Swift can do no wrong.

However, greatness is closely intertwined with dysfunctionality. Take Vincent Van Gogh, one of the most famous and influential painters in artistic history, who was plagued by psychotic episodes and delusions which led to him infamously severing part of his left ear. Or Steve Jobs, the entrepreneur who revolutionized Apple, but also denied paternity of his daughter until it was confirmed by a state-mandated DNA test.

Obviously, greatness and dysfunctionality mean very different things. But what if the two are intertwined, with dysfunction being either a cause or a symptom of greatness?

Dysfunction as a cause of greatness

Often, dysfunction can be the cause of genius. Being truly great, by definition, requires abnormality.

For instance, Nikola Tesla’s obsessive-compulsive disorder might have caused him to invent the Tesla coil and provide the basis for radar, the electron microscope and microwave ovens. But it also could have led to Tesla’s obsession with pigeons and aversion to women wearing earrings.

Pablo Picasso, the founder of the Cubist movement as well as one of the most influential artists of the 20th century, was dyslexic. Picasso’s abstract style was more than likely inspired by his dyslexia, with his paintings being depictions of what Picasso saw.

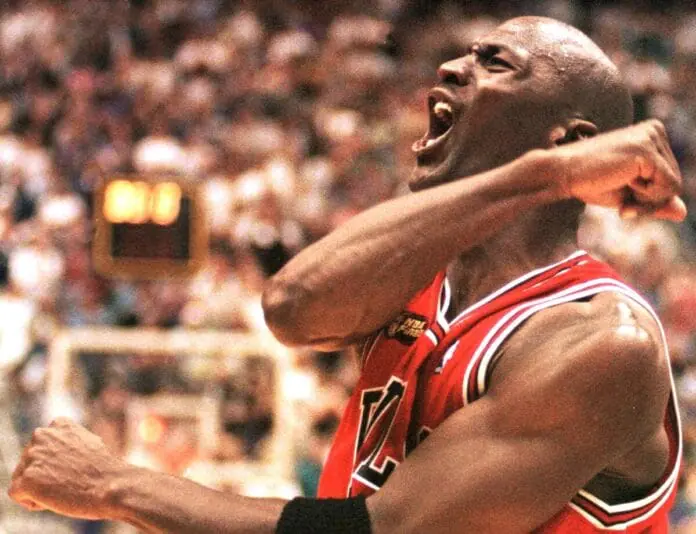

Revolutionary athletes such as Cristiano Ronaldo and Lebron James, both worldwide icons of their sport, are oftentimes regarded as having an inhuman obsession and discipline in their work.

The abnormal and unparalleled drive to achieve greatness and perfection is not uncommon in the world of the “greats”—so much so, that one could argue dysfunction is the very cause of their greatness.

The dysfunctionality necessary to accomplish true greatness can also be a result of one’s surroundings.

Tiger Woods, one of the biggest names in professional golf, was often pushed to a breaking point by his dad during practice rounds from an early age; a parenting technique that would be surely considered dysfunctional by most. However, Tiger Woods went on to reflect on his “psychological training” as being integral to his success.

Tough love also played a major role in World Cup winner Thierry Henry’s astronomical rise to soccer stardom. Widely regarded as one of the best French strikers to touch a football, Henry said that the hardest thing he’s had to do in his sporting career was “to put a smile on [his] dad’s face”. It was likely motivation like this that caused in part Henry to be named Arsenal Football Club’s greatest-ever player among other generation-defining achievements.

Dysfunction as a symptom of greatness

Dysfunctionality is also a direct byproduct of being great. Competing against others who are part of the highest echelon of a field comes with many challenges that can, and do, lead to dysfunction.

Dealing with intense competition in addition to expectations from fans, media and sometimes even yourself, the pressure is bound to be extremely high.

Micheal Phelps, the most successful and decorated swimmer of all time, considered suicide after winning two silver and four gold medals at the 2012 Olympics. Phelps’ post-Olympic depression that he faced after the 2004, 2008 and 2012 Olympics, perhaps stems from a lack of identity when not competing on a global stage.

Another set of challenges brought about by greatness is figuring out how to cope with pressure. Diego Maradona, widely regarded as one of the greatest soccer players in history, was addicted to cocaine, amongst other drugs, throughout his career.

Dysfunctionality also weaves its webs through how society views greatness. We tend to immortalize and elevate who we consider to be “the best” or “great” to a godlike status. This, in turn, rewards dysfunctional behaviour by classifying people as “great” and forming a positive reinforcement cycle.

The rewards offered to society’s elite sometimes go beyond money and fame and include the reward of status. Take French footballer Kylian Mbappé, for example. One of the best and most promising soccer players in the world, he was visited by both the French President and the Emir of Qatar in an attempt to convince him to stay at the footballing club Paris Saint Germain.

With prestige and reputation, in conjunction with massive amounts of money and praise from society, it is no secret that greatness can both be bred by and breed dysfunction.

When looking at society’s greats, it is important to take off the rose-tinted lenses and view them as what they are—humans. Seeing these people as people and observing their dysfunctions can help accentuate their legacy rather than serve to smear it.

Recent Comments