Every year thousands fill downtown Halifax for one Saturday night to celebrate local artists. This year Nocturne: Art at Night still held in-person events, but people from across the world could also tune in from Oct. 12 to 17 for a week of virtual performances.

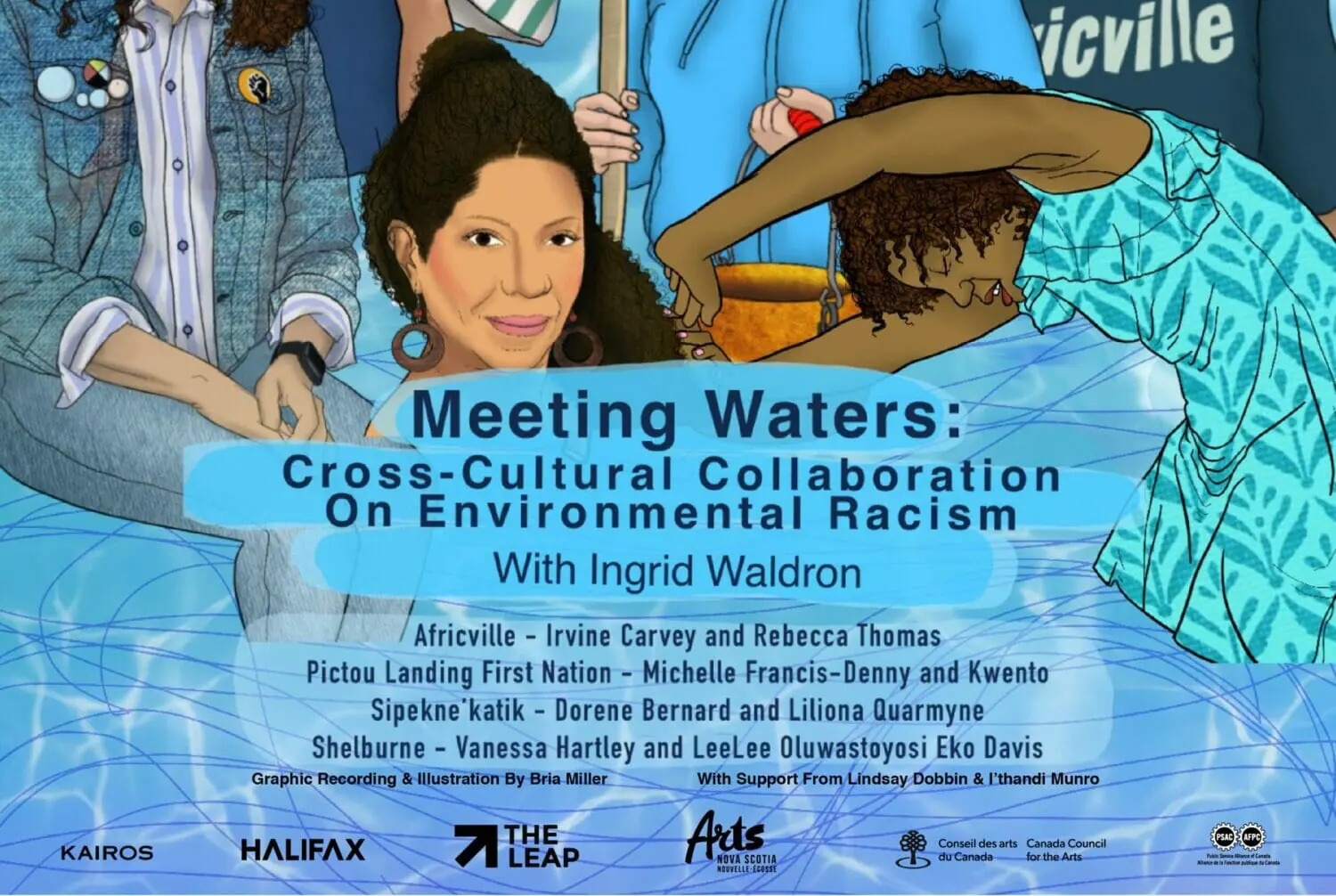

One of those performances was Meeting Waters: Cross-Cultural Collaborations on Environmental Racism, a project by Ingrid Waldron, an associate professor in the faculty of health at Dalhousie University, and Nocturne curator Lindsay Dobbin. The performance was live-streamed via Zoom on Oct. 14.

The project brought together local Black and Indigenous activists and artists to share stories of environmental racism from four communities in Nova Scotia: Africville, Pictou Landing First Nation, Sipekne’katik First Nation and Shelburne.

The idea behind the project

“We wanted to give the artists and speakers free reign to produce something that was interesting, innovative and told a story of the community,” said Waldron. “It was about the artist responding to the community speaker to determine what needed to be shared about that particular community.”

Waldron evolved Meeting Waters from her Environmental Noxiousness, Racial Inequities and Community Health Project (the ENRICH project). According to its website, the ENRICH project is “a collaborative community-based research and engagement project on environmental racism in Mi’kmaq and African Nova Scotian communities.”

Waldron works on the ENRICH project through her employment at Dal. Her book There’s Something in the Water: Environmental Racism in Indigenous and Black Communities inspired a documentary directed by Halifax-born actress Ellen Page.

Meeting Waters differs from Waldron’s other projects with its focus on collaboration.

“It’s not just people sitting side by side on a panel,” Waldron said. “It’s a real collaboration because the product is intersectional.”

In April, Waldron began the project alongside Dobbin. Waldron’s goal was to bring Black and Indigenous communities together. She asked herself, “What does building bridges look like between African Nova Scotian and Mi’kmaq communities, and how can people who are not Black or Indigenous build solidarity with both communities?”

Collaboration between speakers and artists

Vanessa Hartley is an eighth-generation Black loyalist descendent from Shelburne.

“Historically, there has always been solidarity between Indigenous people and Black Loyalists,” Hartley said. “Of course, it has to be strengthened, but we are fighting these battles together.”

Hartley shared the multilayered story of her community with artist Leelee Oluwatoyosi Eko Davis.

“The process with Leelee allowed me to unlock the potential to be artistic,” said Hartley. “It brought a whole new perspective to Shelburne’s history.”

Artist Kirsten Taylor, whose performance name is Kwento, worked with Michelle Francis-Denny to tell the story of Pictou Landing First Nation. Taylor performed an original song entitled “Purple Tides.” Taylor’s song recounts the pollution caused by the Northern Pulp Mill in Pictou Landing, N.S. Wastewater was dumped by the mill into Boat Harbour contaminating the water from 1967 to January of this year.

Born and raised in Preston, N.S., Taylor got her start singing in church. When writing “Purple Tides,” it was important for her to just listen. Taylor internalized Francis-Denny’s experience and wrote from that perspective.

Taylor spoke to Francis-Denny several times, noting what Francis-Denny repeated while sharing the story, hoping to capture what was most important in the song.

“It’s close to Michelle’s heart, so I didn’t want to minimize it,” Taylor said. “Choosing the right words was a challenge.”

Virtual Nocturne still inspires

At the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, Taylor found it hard to be creative. But hearing the stories shared by artists and community members during Meeting Waters relit a spark for her.

“I have been overwhelmed by everything going on today, whether it’s about race or the pandemic. I checked out to protect my own energy,” she said. But Meeting Waters reminded her of the importance of staying aware. “It didn’t feel overwhelming because it was such a loving energy.”

Lindsay Ann Cory, executive director of Nocturne, saw the virtual festival as an opportunity instead of a loss.

“We tried to lead by the artists’ example, highlighting artists that need to be heard right now and should be heard all the time,” Cory said.

Managing virtual spaces meant Cory had to navigate challenging conversations with all the artists about putting their work online.

“We all know the internet and social media are traumatizing places for a lot of people,” said Cory.

Despite patrons watching the performance from their homes, positive feedback still reached the artists, speakers and organizers during Meeting Waters. The Zoom chat room was filled with messages of support and appreciation.

Recent Comments