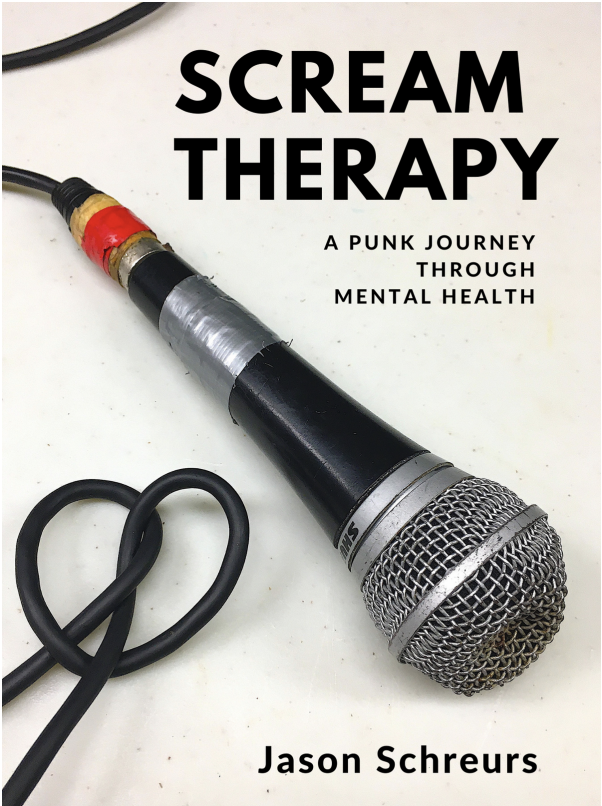

Jason Schruer’s 2023 memoir Scream Therapy: A Punk Journey Through Mental Health examines the punk rock community in relation to mental health.

I know, bizarre right? Who would’ve thought the studded leather “weirdos” would give a damn about mental health?

While they haven’t always been direct, discussions about mental health have been going on for a long time. Screaming into the mic about institutionalization (Suicidal Tendencies, 1983), feelings of atomization (The Clash, 1979) and substance abuse (Sorority Noise, 2015) are all punk rock rallying cries.

Schruer delves deep into the psyche that brings someone to continuously play shows where they may inexplicably end up with shards of glass embedded in their bleeding wounds. This iexact situation happened to Schruer, as described in his book.

Stage diving into therapy

Through recollections of a long punk career, Scream Therapy brings the uninitiated the (relatively) controlled mania of the punk rock community. All those times you’ve found yourself developing nervous ticks, or unable to think past deadlines and readings, maybe the meditation you needed was screaming it out in a mosh pit.

The perception of punk rock can be pretty narrow: loud, fast and chaotic. While this is certainly the basis for a portion of the genre, it comes nowhere close to covering the whole.

Punk includes the good, the bad and the weird. The attitude is often “Go eff yourself, I’m writing my own damn weird song”. Song topics include counting down the seconds until you can be sedated (Ramones, 1978) or even just wanting to watch TV with your friends (Black Flag, 1981).

Schruer sheds light on this community’s knack for screaming in just the right way.

I was lucky enough to attend a reading that Schruer gave at the Halifax Central Library. He spoke about a change in the language regarding mental health. Often we hear about “recovery language”, wherein people will use language that encourages hope, optimism and support that the person suffering can get better or be “cured” in regards to mental health.

Schruer argues for “transformative language”. Rather than talking about how he might be able to “get better,” he focuses on how he might control or utilize his unique mental state to develop himself.

The tortured artist is an old joke at this point. The idea is that artists might pull from the depths of their suffering to create art with real substance. This way of thinking runs the risk of romanticizing mental illness, and the punk rock community rides that line.

Unleash the anguish

Punk rock is often a very raw expression of anguish, acting as a method to unleash that anguish in a way that doesn’t hurt anybody or anything (except perhaps your eardrums).

It’s not all roses in the mosh pit. During the Q&A, after his reading, Schruer commented on some of the uglier sides of punk rock.

He focused on the straight edge movement, which advocates against alcohol and other drugs and encourages its followers to live the boy scout life. In contrast to Black Flag’s song “Six Pack” which humorously criticizes people who overindulge in liquor, some straight edge followers take an almost militant stance.

Schruer compares them to high school jocks. He thinks the similarities lie in the exclusionary attitude, jaded criticisms and elitism that permeate the straight edge community. There are still douchebag punks.

Through punk rock, musicians and fans alike can transform their pain and struggles into a community of misfits. Of lil jack asses who say eff you to everybody, they say eff you to each other, but it’s with love.

Punk and similar communities may appear hostile to some newcomers, but once you make it through that initial hazing and find your inner circle, you’ll be in on the joke.

Recent Comments