Polluters go to Mi’kmaq or African Nova Scotian communities not only for their inexpensive land, but also because these communities don’t have the political power to resist polluting industries.

This was one of the many things discussed at The Canadian Centre for Ethics in Public Affairs’ (CCEPA) Sept. 10 lecture focusing on how Nova Scotia’s environmental racism fits into broader issues of capitalism and colonialism.

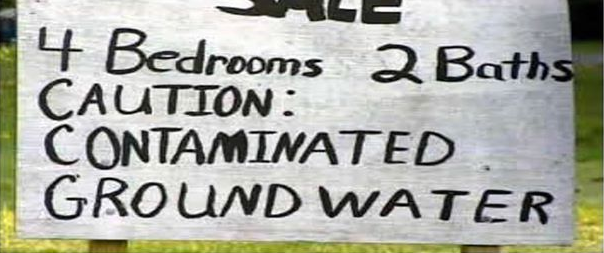

Environmental racism is defined as the “placement of low-income or minority communities in proximity to environmentally hazardous or degraded environments.”

Ingrid Waldron, an assistant professor at Dalhousie’s School of Nursing, made the point about Nova Scotian polluters. She has researched environmental racism in Nova Scotia since 2012. Most of her research involves listening to people from communities that directly face environmental racism.

“What I like about this project is that there’s a community activism piece, where you’re actually doing something real in the communities,” Waldron said, “and an intellectual piece where, for the first time, I’ve really been able to explore tonight [at the lecture].”

Nova Scotia has a history of environmental racism and Waldron believes that, for social and economic reasons, racism is written into environmental policy.

Dumps have been located in African Nova Scotian communities for decades, including Africville and Lincolnville.

When a pulp mill was built near the Pictou Landing First Nation reserve, a waste treatment lagoon was located there. The toxic waste in Boat Harbour, now scheduled to be cleaned up by 2020, destroyed hunting and fishing for the people of Pictou Landing.

In Waldron’s research, communities have shared the prevalent health concerns that they feel are caused by industry, such as rare cancers, asthma, heart disease and diabetes.

Though Nova Scotia’s government acknowledges environmental justice, it has yet to acknowledge environmental racism.

Waldron said that the first step to ending environmental racism is acknowledging the differing interests of various communities and allowing marginalized groups to become involved in environmental policy.

This spring, Waldron collaborated with MLA Lenore Zann and introduced Bill 111, An Act to Address Environmental Racism, to the province’s legislature in April. The bill was not supported by the Liberal party, but will be revisited in the coming months.

“That bill would be the first step in engaging with communities on a serious level: talking to communities and getting them to share their concerns, then eventually being able to address their concerns,” Waldron said.

The bill would not only be important in terms of symbolism, Waldron added, but in terms of the practicality of cleaning waste sites and avoiding harm to the “health and well being of community members.”

Waldron wants the government and all Nova Scotians to understand the importance of race in environmental issues and to be more accountable for the environmental harm being done.

Recent Comments