When Russia started the invasion of her country, Dalhousie University student Dali Kapanadze woke up every day shaking. In early March, her family made it from Kyiv to Poland. She is now working to try to get them to Canada.

Kapanadze is a fourth-year student from Kyiv studying microbiology and immunology. She moved to the United States six years ago for high school and moved to Canada three years ago to attend Dal. She hasn’t been back to Ukraine since December 2019.

Hundreds of thousands of refugees have tried to flee the country into Poland for safety. Kapanadze’s family, her mother and grandmother, arrived in Poland shortly before the invasion started.

“Now I’m working on getting them here, and sending money to the funds that go to humanitarian support and military support there,” said Kapanadze.

Kapanadze said she’s also working out her own finances in order to help support her family, “there will be little to no refugee support in Canada once they arrive.”

As of March 10, Canada is in discussions with Poland to welcome Ukranian refugees to the country, but nothing has been implemented yet.

“I don’t have the means to bring in two more people and have them taken care of. Neither does my partner. It’s a big ask,” said Kapanadze.

When the attack on Ukraine began, she watched the news non-stop. Her professors helped her where they could, but she feels that there is only so much help she can take right now.

“I took a little less than a two-week pause, and even now that I’m physically in class, I’m still incredibly behind, so no, it’s not good. I will pull through it,” said Kapanadze. “The best help for my family right now is for me to graduate and be able to support them.”

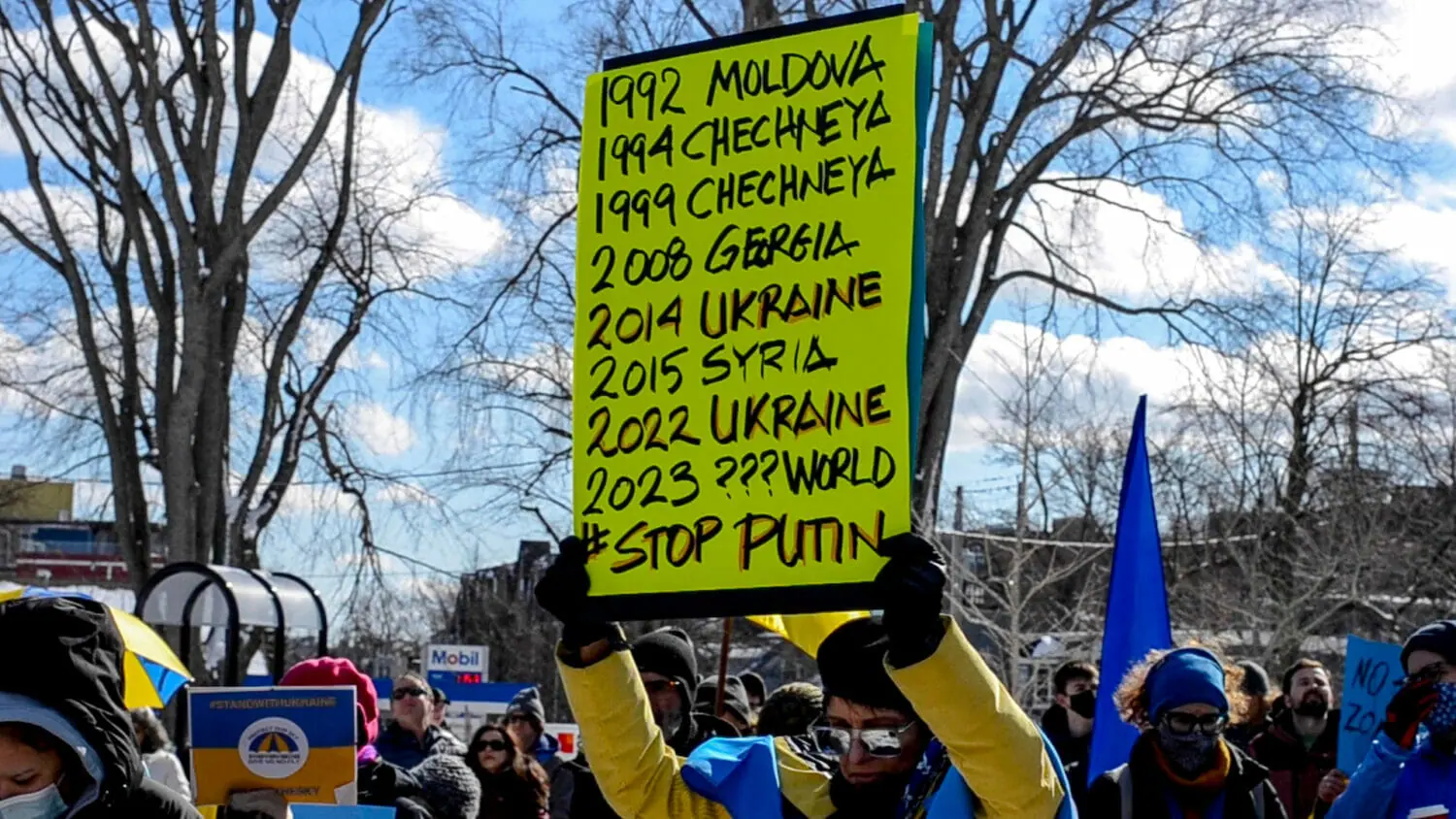

She said she isn’t surprised this is happening. She grew up watching Russian aggression, she just didn’t expect it now.

“I’m half Georgian … Our relatives in Georgia, they have suffered from Russian aggression in 2008,” said Kapanadze.

In August 2008, Russia invaded Georgia in support of breakaway provinces. Putin justified his war by claiming that Georgia was committing an “ethnic cleansing” of Ossetians and that his support of the self-proclaimed republic of South Ossetia was to prevent this. The war lasted 12 days and would result in hundreds of deaths of soldiers and civilians.

In 2014, Russia launched an invasion into the southern Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea. Russia has continued to occupy the area and stoked further tensions in the eastern Ukrainian region of Donbas.

“The Western world basically gaslights the shit out of them. And they gaslit the shit out of us with the occupation of Crimea in 2014. And with the bloody war that they started eight years ago, this is not a new war.”

Emilie Quinn is a fourth-year political science and history student doing her thesis on the cost of the Crimean war. She said that the dissolution of the U.S.S.R., Ukraine has been fighting for their place. Comparing her work to today’s war, she is unsure of the impact that actions of the West will have.

“From a political science point of view, [sanctions] work on people who are thinking rationally, but I think that what Putin is thinking is more complex than that. He really wants to test the world and NATO’s capacity.”

On March 10, the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences hosted a forum with experts from Dal, Saint Mary’s University and Mount Saint Vincent University.

“The road will be long and the cost will be heavy,” said Denis Kozlov, associate professor in the Department of History, at the event.

Ruben Zaiotti is the director of the Jean Monnet European Union Centre of Excellence at Dal. He hosted the event. In an interview with the Gazette, Zaiotti said he believes this war will continue for months or more. “It depends what Putin’s ultimate objective is … If it’s control Ukraine, then that could last a very long time.”

He said that the situation is evolving quickly, but this is the start. “It’s the next phase, that’s going to be the most difficult one, it’s about controlling the country, a.k.a., basically occupying the country after that, you know, Russia might be able to put somebody friendly in power in Kyiv.”

When thinking of her home, Kapanadze said that the West needs to do everything they can to help. She said that although sanctions will predominately impact Russian citizens, that may be what it takes to make an impact.

“The people who understand that this is not right, they’re not willing to do something actively to change it. And the people who are doing something actively to change it, they’re using wrong approaches,” said Kapanadze.

”[it’s a] privilege of other European countries where you can go to the peaceful protests and have an impact on the decision making of your government,” she said. “In a totalitarian regime, that is not an option. And an attempt of changing your government’s policy with a peaceful protest is the equivalent of, I don’t know, mashing your potatoes with a microscope.”

Kapanadze received an email from Dal with how they can help. “They told me that they’re here for me, and they feel I could go to university counseling. That’s the support that I got,” she said.

She said people in Halifax can take obvious steps to help: attend rallies, support humanitarian and military funds, and call on politicians for increased intervention and aid for Ukraine.

When her family and other refugees make it to Canada, Kapanadze said that we all need to help out. Businesses must keep jobs available, housing must be provided and everyone needs to pitch in to support them.

Recent Comments