The packaging is plastic, the applicators are often plastic, and they can produce up to 136 kilograms of waste in a person’s lifetime.

Despite this, pads and tampons are still the most widely-used period products on the market. The menstrual cup is another option for periods that is not nearly as widely used but can have positive implications for reducing waste, cutting costs and, in some cases, preventing period poverty.

What is a menstrual cup?

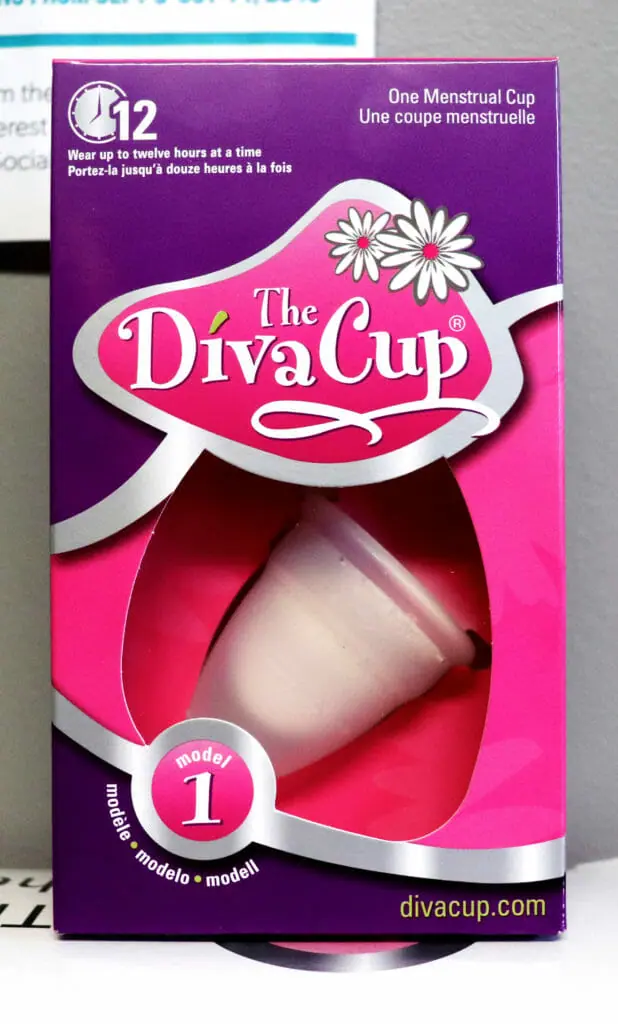

The modern menstrual cup has been around since 1937. Today, there are dozens of different menstrual cup brands, each offering different shapes and sizes of cups. Worn internally, the menstrual cup is designed to collect blood rather than absorb it. It can be worn for up to 12 hours at a time and is even safe to wear while sleeping. There is a risk of toxic shock syndrome, though it’s very rare.

Depending on their shape, some menstrual cups are okay to leave in during sex.

The menstrual cup is made of silicone, so when it’s time to change, the user simply empties its contents and washes it with soap and water. Most companies that make them recommend boiling menstrual cups in water after every cycle.

Switching it up

“I expected it to be a little uncomfortable,” says Samara Belhomme, a second-year applied computer science student at Dalhousie University who started using a menstrual cup a year ago. “But once it’s in there I can’t feel it at all, which I was really surprised about. I just completely forget about it until it’s full.”

Sydney Patterson, a sociology student in their second year at the University of King’s College, volunteered at a sexual health information centre in Toronto where learning about menstrual cups was part of their training.

“I would probably recommend you try it at home, not on a busy day, and just get comfortable before you use it on heavy days or when you’re out and about,” Patterson says.

Because menstrual cups are reusable, they are often praised for being environmentally friendly. For Hope Moon, a second-year King’s student majoring in environmental and contemporary studies, one of the most compelling reasons for her to switch to a menstrual cup was because it eliminated all “the rounds of period waste.”

“Another pro is that you get really used to and comfortable with your body, and what it produces,” Moon says. “Although it sounds kind of gross, you get to feel like it’s not gross anymore and it becomes normal.”

Cutting the cost

According to a report from the Canadian Public Health Association, people with periods will spend an estimated $6,000 on menstrual products over the course of their lifetime. Depending on the brand, the price of a menstrual cup can range from $15 to $75. South House Sexual and Gender Resource Centre on Seymour Street sells menstrual cups for only $20.

Brooklyn Connoly, a third-year journalism student at King’s, considered cost when she chose to use menstrual cups.

“I don’t have to go out and buy pads and tampons as often,” Connoly says. “So, it’s a big spend at first, but it really does work itself out in the financial department.”

Period poverty

Leigh Heide is the provincial coordinator for Sexual Health Nova Scotia, an organization that represents sexual health centres all over the province, including the Halifax Sexual Health Centre. Last October, Hyde attended the Period Poverty Summit co-hosted by two provincial organizations, Friendly Divas and Dignity. Period. The goal of the summit was to raise awareness about period poverty.

“People living in poverty struggle to get the things they need, which also affects them in terms of supplies that they need for periods and all their menstrual needs,” Heide says.

They explain that period poverty is a widespread issue in Nova Scotia, especially in rural areas. For people living in those areas, the menstrual cup can eliminate the monthly expense of period products.

“The caveat is that menstrual cups don’t fit everybody’s needs…being able to empty and clean them if you don’t have clean water, for instance,” Heide says. “So, they’re not a solution for every single person but they are a great solution for a lot of folks who need something that they don’t have to pay for every month.”

Despite the challenges presented by period poverty, Heide remains optimistic.

“Period poverty is getting a lot more conversation. I wasn’t aware of the term until about a year ago myself, and now I feel like I’m hearing it a lot,” they say. “That conversation also really needs to include our Department of Health and our schools, larger systems that can make a difference.”

Recent Comments