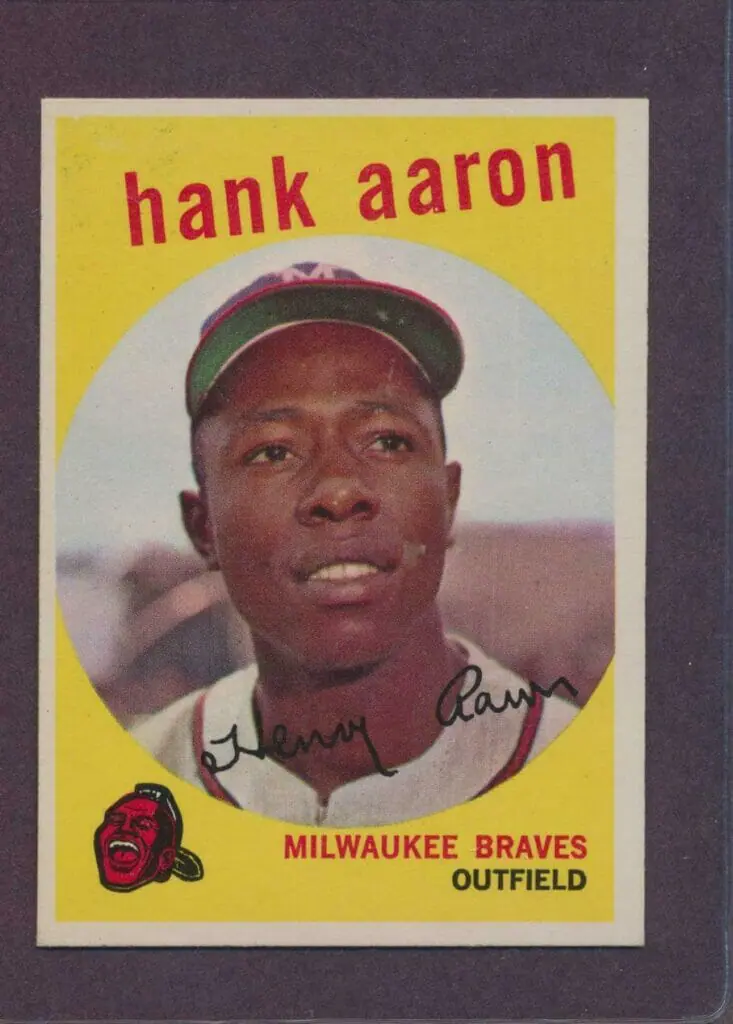

When Hank Aaron retired from baseball in 1976, he did so as one of the greatest baseball players of all time. Aaron died in his sleep on Jan. 22, 2021. He was 86.

The feat he’s most famous for was breaking Babe Ruth’s career home run record of 714. Even after Barry Bonds eclipsed that record in 2007, Aaron still holds the Major League Baseball (MLB) record for career runs batted in (RBI) with 2,297 and total bases with 6,856. He is third all-time in career base hits with 3,771.

Before taking the MLB by storm, Aaron got his start playing for Negro League teams like the Indianapolis Clowns. In a recent decision, the MLB elevated the pre-1948 Negro Leagues to the status of the American and National leagues. This means while Negro League statistics before 1948 are included in MLB record books, Aaron’s five home runs he hit for the Clowns are not counted as part of his major league home runs, having debuted in the ’50s.

Although they may not leave a huge impact on where he stands in all-time leaderboards, the Leagues (before and after 1948) are commonly considered to be roughly as good as the MLB at the time. Considering players like Aaron played in the Negro Leagues after 1948, perhaps it’s time to elevate all Negro League stats to the major league level.

Paving the way for Black baseball players

Aaron’s Hall of Fame career came to be over the course of three decades worth of civil rights movements in the United States. Growing up playing semi-pro baseball in Mobile, Ala., he broke the colour barrier in the South Atlantic League in 1953 with the Jacksonville Braves.

Early in his pro career, Aaron’s time in the minor leagues is often forgotten, but might be just as important as his MLB accomplishments. Throughout the season while playing in southern American states that enforced Jim Crow laws, Aaron, his fellow Black teammate Horace Garner and Puerto Rican native Félix Mantilla experienced racist abuse from both Jacksonville’s and its opponents’ fans.

Despite this abuse, and not being able to live, eat or stay at the same hotel as his teammates, Aaron was described by Jacksonville manager Ben Geraghty, in a 1957 Sports Illustrated interview, as “the most relaxed kid” he ever saw.

It’s easy to forget widespread racism in baseball didn’t disappear with Jackie Robinson signing with the Brooklyn Dodgers. Robinson opened a path for other People of Colour into the MLB, but the injustices he faced with the Dodgers, and the entrenched racism that Aaron had grown up in, was felt by every Black player trying to make it to the major leagues. The abuse would continue through Aaron’s career, especially as he closed in on Ruth’s home run record.

Recognition of the Negro Leagues

Just as Robinson’s historic appearance with the Dodgers didn’t end racism in the major leagues, it didn’t immediately end Black baseball as it had existed for decades as the Negro Leagues. In his first professional contract, Aaron had previously played in the Negro American League for the Clowns in 1952.

The Negro Leagues of the early to mid-20th century boasted players of extraordinary talent, though many aspects and initiatives in the leagues were underfunded and disorganized. Immediately after Robinson broke the colour barrier, the best way for a Black player to make it to the majors was through the Negro Leagues even if only a brief stint like Aaron had with the Clowns.

“It’s easy to forget widespread racism in baseball didn’t disappear with Jackie Robinson signing with the Brooklyn Dodgers.”

Players Like Aaron, Ernie Banks and Willie Mays — all Hall of Famers during the ’50s and ’60s — got their starts in the dying days of the Negro Leagues. So the possibility that their achievements as Negro League players after 1948 might now be included as MLB-calibre is an interesting and exciting prospect.

While disorganized, the Leagues had spent decades growing into a premier competition with immense talent, and while breaking the colour barrier was the best thing that has ever happened in major league baseball, it severely hurt the Negro Leagues.

In this sense, the Negro Leagues sort of went out with a bang. It wasn’t from a lack of talent that doomed the Leagues, but issues on the organizational side. How can we overlook these players simply because of how the Leagues were run aground? That’s like saying if the MLB went broke today then the next baseball league wouldn’t recognize present-day stars like Trout, Mookie Betts or Bryce Harper because they were only around near the end.

As with the MLB, the calibre of competition in the Negro Leagues remained consistent throughout as elite-level baseball. And Aaron, the greatest player to ever come through the Leagues, played after 1948. Could that mean the post-1948 era was even better? Regardless, the whole pre-1948 rule just doesn’t make sense.

Validating Negro League achievements from post-1948 would go a long way in acknowledging how Black players joining the MLB was a process and not a moment frozen in history. It would further cement Aaron’s reputation as one of the greatest baseball players ever and one of the greatest athletes to lead the way for Black players into the upper echelons of their respective sport.

Recent Comments