Hannah Pletz grew up on Vancouver Island. Her first sexual health lesson was in fourth grade. She learned the basics: periods, pimples and pit-stains.

But when high school sex education started, Pletz wasn’t satisfied with what was being taught.

Lack of inclusion

Natalie Rosen is a sex therapist and associate professor at the department of obstetrics and gynaecology at Dalhousie University. She says it’s important for schools to have some level of standardization in how sex education curriculums are being delivered to students. It’s also essential that those curriculums be inclusive.

Sex-ed “needs to be much more inclusive in terms of the language that is being used and in terms of not making assumptions,” says Rosen, “like being heteronormative for example.”

Pletz, who currently attends Dal, says inclusiveness is exactly what her sex-ed was missing.

“Sex education is very complicated,” says Pletz. “There are the basics, like how sex works … then there are all different types of contraception, everything about consent, and then all the different types of people who can have sex.”

Pletz says her teachers did a good job with explaining consent and all the different types of birth control. By the end of the unit, she and her classmates were well-versed in STI knowledge. But Pletz wishes her teachers at least “acknowledged that gay people actually existed.”

“We learned absolutely nothing about anything other than heterosexual coupling,” Pletz says. “I didn’t know that dental dams existed until I went to a pride parade a few years ago, and I’m a lesbian … that’s really the only form of protection we have.”

Rosen says in sex-ed, it’s important that all students “feel like their experiences are reflected in the curriculum.”

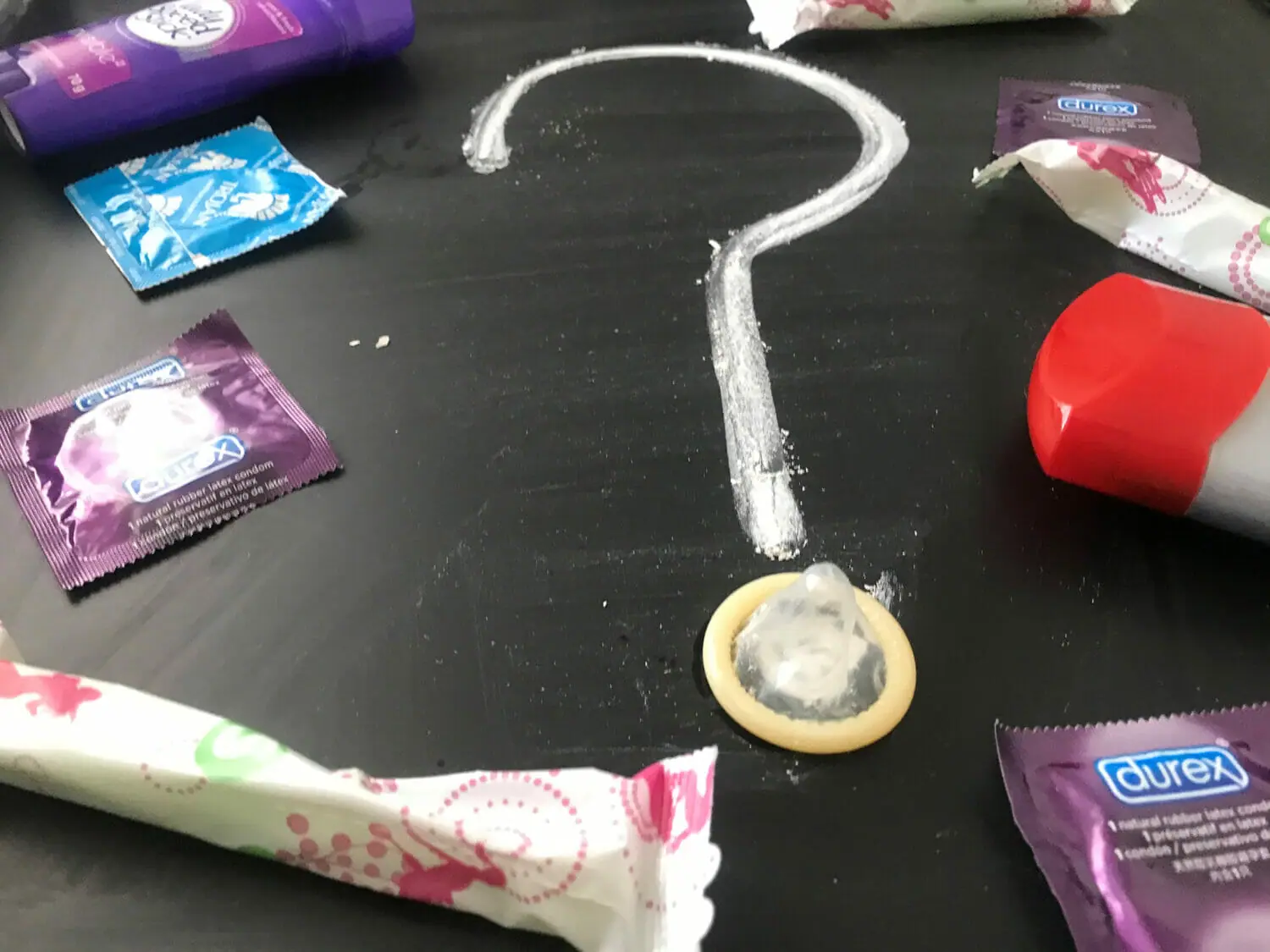

Pletz never felt uncomfortable during sex-ed classes. Her school would pay older students called “sexual support peers” to talk to Grade 9 and 10 students about things like condoms and lube. But the classes only covered what most straight and cis-gender people needed to know.

Ineffective education

Gideon Morton didn’t feel satisfied with his high school’s sex-ed curriculum either. Morton is a student at the University of King’s College. He went to high school in Vermont.

“The class that I took was a weird, remedial online course,” he says. “The textbook was literally some 1950s, American, conservative nonsense.”

Morton ended up ditching the textbook that focused on abstinence to figure things out by himself.

“By grade 12, I had experience,” he says. “I knew how to use a condom and understood all the different types of birth control … so I wasn’t really lacking anything, but the course definitely was.”

Neil Kahn, a Dal student, says it wasn’t what was being taught that was the issue with his sex-ed. It was the fact that lessons weren’t “being heard.”

“Most of the kids weren’t even paying attention,” says Kahn about his high school class in Ottawa. “I know personally I was playing cards at the back of the classroom while a video was playing in the background.”

A “fairly OK” experience

Annie McCarthy, a King’s student, says her high school teacher in Truro was the reason her sex-ed was “actually fairly OK.”

“I was in French immersion and [our teacher] taught us in English because she knew how important it was,” says McCarthy.

McCarthy’s class made PowerPoints about the different types of birth control and discussed the consequences of unprotected sex in a non-judgmental environment, which according to McCarthy, kept her and her classmates engaged in the material.

Riley Arseneau, a Dal student, also feels she received decent sex-ed at her Ottawa high school. Her Grade 9 health curriculum was focused on a two-day presentation that looked at different sexual identities, how to use pronouns and where to find LGBTQ2S+ support groups.

Arseneau appreciated her school’s efforts of making their sex-ed inclusive but still felt like she missed out on learning basic information.

“I wish we learned a little more about sex itself,” she says. “We talked about the types of birth control but didn’t go into much detail about how they worked. We also didn’t talk about consent as much as we should have.”

Ultimately, Dr. Rosen says sex-ed is a personal experience, and the way it’s delivered differs depending on who is learning it and where it’s being taught. Rosen thinks that in order to make sure everyone gets the sex education they need, schools need to provide safe, inclusive spaces outside of health classes where students feel comfortable asking questions.

Recent Comments