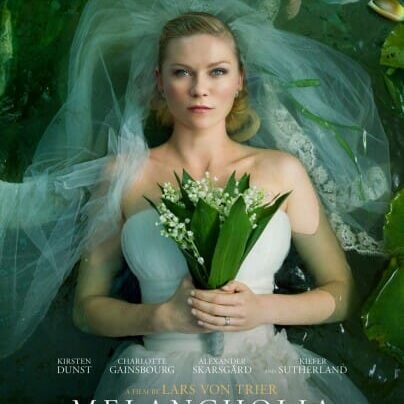

Flicks Review: Melancholia

Melancholia is a bad date movie—unless your date is Nietzsche, who’d be hot under the collar for the Wagner and nihilistic melodrama.

Melancholia is a bad date movie—unless your date is Nietzsche, who’d be hot under the collar for the Wagner and nihilistic melodrama. The movie starts suddenly; cue slow-mo apocalyptic dream sequence, end light-hearted conversation—you’ve entered writer/director Lars Von Trier land.

Melancholia is a bad date movie—unless your date is Nietzsche, who’d be hot under the collar for the Wagner and nihilistic melodrama. The movie starts suddenly; cue slow-mo apocalyptic dream sequence, end light-hearted conversation—you’ve entered writer/director Lars Von Trier land.

A star appears above a wedding reception on a vast estate. Such a low-profile intro of the sci-fi element is a clue that this drama goes light on Ewoks and heavy on the two leads, Kirsten Dunst and Charlotte Gainsbourg, artfully imploding in the foreground of eerily pretty visuals. Von Trier sustains menace, lacing shots with nature-gone-awry imagery—the movie’s primal subconscious—while the planet Melancholia nears on a crash-course toward earth.

As a meditation on depression, it’s searing. Von Trier’s assembled a Dostoevskian cast of characters whose collective moral failings deconstruct life’s consolations. Marriage, childhood fables, religion, the rationality of science, and finally the comforts of wine and terrace all collapse before the mysterious power of the approaching planet. The planet could be death itself: In Von Trier’s closed universe, unlike Shakespeare, the weather doesn’t mirror human turmoil, but leaves characters powerless before its fathomless course. Von Trier captures how even terribly depressed characters, like Justine, nurture an insatiable appetite for beauty. Melancholia isn’t sentimental; yet, for its steel-set pessimism it doesn’t skimp on beautiful cinematography: overhead shots of foggy morning horseback riding, unearthly double lightings of moon and Melancholia, or Charlotte Gainsbourg looking pensive.

You appreciate Melancholia more in retrospect, when its heady symbolism—lunar goddesses, nods to depressed philosophers and inverted plot parallels—has a chance to settle with you. But, like his notorious public appearance at Cannes where the director made jokes about being a Nazi, some of Von Trier’s filmic provocation does not translate well.

It’s hard to take Melancholia as seriously as it seems to take itself. In the end, not even a decidedly non-Bauer-esque, Kiefer Sutherland can save the film from self-importance. With Von Trier, biblical-scale grandeur comes second hat. Founding member of Dogme 95— the collective of realist filmmakers infamous for cinema verite-the only remnant here of which seems to be a shaky handheld camera—Von Trier has inadvertently demonstrated one of the defining traits of serious depression: the absence of humour and the perspective it lends on life’s darker realities.

Melancholia belongs to a new crop of recently released sci-fi drama, and it’s wonderful to see the genre mature beyond late-seventies kitsche. Equally harrowing and artful meditations Tree of Life and Another Earth, have more emotional accesibility and less, well, Melancholy.

This is an obscenely self-assured movie, or is that just the Wagner? If you seek out risky, visionary cinema, then I couldn’t keep you from this trippy downer of a film anyway.