Nova Scotian author releases new English translation of essays by French-Swiss modernist writer Blaise Cendrars

The new translation was released on Nov. 1

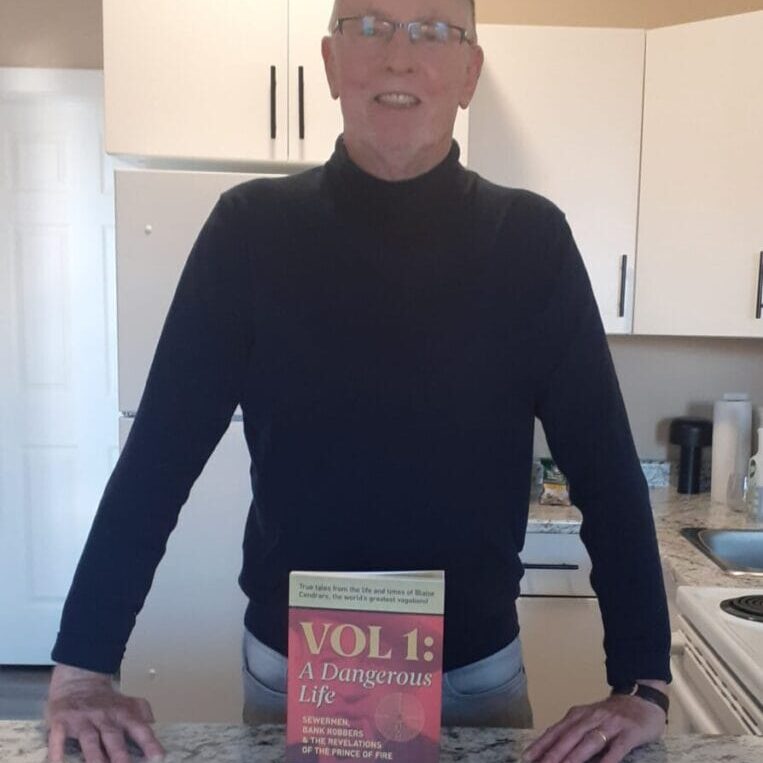

Nova Scotia author David MacKinnon’s latest work, an English translation of works by French-Swiss writer Blaise Cendrars titled A Dangerous Life: Sewermen, Bank Robbers & Voodoo Killers, was released on Nov. 1.

A Dangerous Life features his translations of seven true tales from the life and times of poet Blaise Cendrars — “the world’s greatest vagabond,” according to the book. MacKinnon’s previous books include Leper Tango, The Eel, The Voluntary Crucifixion and a critically acclaimed translation of radio interviews with Cendrars, Blaise Cendrars Speaks.

True tales

In 1911, a man named Frédéric-Louis Sauser composed Easter in New York, a part hymn, part beatified rap poem. Sauser completed the poem and signed it with the name Blaise Cendrars, which means “the man rising out of his own ashes.” According to MacKinnon, the staccato rhythms of the piece were a century ahead of its time..

Cendrars was left-handed but lost his left arm serving as a foreign legionnaire in the First World War. After the war, Cendrars learned to write with his right hand. Most of Cendrars’ first-person reporting, which he called “true tales,” had not been translated.

“I felt that people haven’t seen the realistic, true-tale type of writing that Cendrars does,” MacKinnon said. “One of the stories I’ve translated is ‘River of Blood‘; it’s actually ‘J’ai Saigné,’ which is ‘I Bled,’ and it’s about the day he had his arm shot off by a German machine-gunner.”

In A Dangerous Life, this story is titled “Take This Cup of Blood.”

According to MacKinnon, only Robert Graves in Good-Bye to All That and Erich Maria Remarque in All Quiet on the Western Front resemble Cendrars’ style.

“It’s simple and it’s spare, but it conveys the extent to which the real criminals — and I believe this too — that set the stage for what happened later are the generals of all the countries involved in World War I,” MacKinnon said. “They’re the killers of the flower of youth.”

Cendrars responded to the aftermath of the First World War in 1918 with Take This Cup of Blood. He also composed an accompanying piece called I Have Killed, which offers a first-person account of killing a German soldier in the trenches. MacKinnon emphasized that there are almost no such accounts, aside from those by Graves and Remarque.

“After you read Cendrars, the war films — outside of the strategic ones like A Bridge Too Far and all that — are so bad, so disrespectful to the tragedy of what these kids went through,” MacKinnon said.

The convergence of rhythm and prose

MacKinnon attended a poetry reading on the University of California, Berkeley campus, where Allen Ginsberg read his poem “Howl” with a “boom-boom, tan-tan” beat.

“I’m listening to him do it, and I’m going, ‘Shit, it sounds like rap,’” said MacKinnon. “It’s all percussive. It is beat, and I saw the deliberate edge to it.”

Before the reading, MacKinnon had reached for his copy of Easter in New York by Cendrars and read it aloud to himself.

“I wanted to give them a sense of this poem that revolutionized French poetry and that they should actually tune into. So I’m doing it, and I’m going, ‘Shit, this sounds like rap too.’”

MacKinnon says critics, academics and creative writers tend to operate on an “in-built prejudice” that art or writing is something that evolves. He dismisses schools of writing, instead claiming writers such as Ginsberg and Cendrars, though separated by decades, tapped a common source.

“My take is not that Allen Ginsberg was influenced by it,” MacKinnon said. “Allen Ginsberg stuck his ear to the ground, and Cendrars did the same thing.”

Two nights before the reading, MacKinnon searched for a combination of terms like “rap,” “Cendrars” and “poem.” He discovered a rapper in the suburbs of Paris performing Cendrars’ Easter in New York, about a century after it was published.

In the foreword to A Dangerous Life, writer Jim Christy said, “The effect of the stories, a phantasmagoria of the possibilities of being alive, would be overwhelming were it not for Cendrars’ rhythmic, indeed, orchestrated prose. Some English-language critics have compared Cendrars to Ernest Hemingway. These people, mostly Americans, should do serious penance. Henry Miller said, ‘Blaise Cendrars is the man Hemingway wanted to be.’ Compared to him, Poppa was a boy scout.”

On Nov. 1, MacKinnon’s translations of Cendrars, A Dangerous Life: Sewermen, Bank Robbers & Voodoo Killers began to be distributed in Canada by the University of Toronto Press.