Dissected: Dal keeps cadaver searching alive

Because of people like Wendy Simon, people like Jade Panzarosa don’t dig corpses from graveyards under the cover of night

Because of people like Wendy Simon, people like Jade Panzarosa don’t dig corpses from graveyards under the cover of night. Jade is a 3rd year neuroscience student.

On the 12th floor of the Tupper Building, she pulls a human brain from its plastic container and the classroom smells like formaldehyde. There are roughly 50 students and 16 whole brains – and some half ones. They are learning about the cerebellum and prepare for upcoming exams.

Course instructor William Baldridge, head of Dalhousie’s department of medical neuroscience, gives a short lecture before the lab begins. The goal is to identify parts they learned about in textbooks and diagrams – the olfactory bulbs, for example, or the diaphanous dura mater.

It’s particularly difficult to find the insular lobe – it’s just not clear where it begins and ends – so the students use the Circle of Willis as a landmark. The Circle of Willis is a series of arteries that looks a bit like Toronto’s subway map. The arterial systems, lobes and stems are all much easier to find on the plastic models sitting on the tables, but that’s what makes the prosection (a dissection of an individual cadaver part) so important.

“It’s so much more interesting and better than looking at the diagrams. There are individual differences between brains,” Panzarosa said. “It brings the concepts together.” Baldridge walks from group to group and helps them spot things they didn’t on their own, and a half hour after they began, the students put the brains back into the containers. “What makes this old science of anatomy still relevant and totally essential is the three-dimensional aspect,” Baldridge said. “There’s no book or computer screen that can replicate the 3D experience, and, as the joke goes, doctors will usually find most of their patients are in 3D also.”

Human dissections can be traced to the beginnings of anatomy itself. The Edwin Smith Papyrus, an analysis of 48 bodily injuries dated to the Second Intermediate Period of Ancient Egypt, is the earliest anatomical text. However, Galen of Pergamon is widely considered the father of anatomical medicine, whose texts were studied by medical students into the 19th century. Rome forbade human dissection in 150 BC. While Galen only examined animal cadavers, he quoted anatomists Erasistratus and Herophilos extensively, who performed countless vivisections on prisoners a century earlier.

A bit later, in newly indepen- dent America, surgical research was developing boomingly by the late 1700s, but the popularity of surgeons in the public sphere was most definitely not. It’s hard to imagine how doctors, individuals so highly respected today, were the subject of popular fear and enmity in cities with established medical colleges such as New York and Baltimore. The Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons was then the site of the USA’s first grassroots riot.

It all began in 1788 when the city’s unpoverished classes realized their lifeless white bodies weren’t beyond the hands of the resurrectionists. While crowds protested individual cases of grave-robbery and dissection, resurrectionists were generally safe sticking to cemeteries for paupers and blacks. At the time, a popular place for ambitious cadaver-hunters in New York was Pottersfield; located beside an alms house with a separate plot for black internees, it was the site of constant body-snatching.

Eventually, the free black community responded. In February 1788, they petitioned the city to stop robbers robbing their grounds, citing that surgeons “dig up the bodies of the deceased, friends and relatives of the petitioners, carry them away without respect to age or sex, mangle their flesh out of wanton curiosity and then expose it to beasts and birds.” Their leaders’ proposal to allow and limit dissection on bodies of criminals was a critical precursor to the anatomy act, which came as a response to the “Doctors’ Riots”.

Those riots happened in April, after a group of irritating children ran into an irate physician at the New York Hospital. As a boy from the group stared into a hospital room from an outside window, so the story goes, a physician waved a dismembered arm to scare him away. He reportedly yelled out that the cold, floppy limb was in fact the boy’s mother’s.

When a gathering crowd discovered shortly thereafter the empty grave of the boy’s recently- deceased mother, chaos ensued. Rioters broke into surgeons‘ homes and the hospital searching for human remains as anatomical specimens and tools were destroyed, and medical students were pulled onto the streets. The next morning, the mayor ordered the medical community be escorted into the jailhouse for protection. Soon, a line of militiamen summoned by the governor separated the doctors from a mob 2,000 deep. The mob attacked the militiamen, the militiamen fired, and at least three rioters lay dead, with dozens more wounded.

The event pushed anatomical dissection to the fore of public debate. In 1789, a bill entitled An Act to Prevent the Odious Practice of Digging up and Removing for the Purpose of Dissection, Dead Bodies Interred in Cemeteries or Burial Places recognized the legitimacy of the anti-dissection protests while acknowledging the importance of cadavers for research. The law allowed bodies of executed murderers, arsonists, and burglars to be handed over to surgeons, and gave judges more freedom to sentence body-snatches on a case-by- case basis. But the maw of science was quenched only until the curtailment of death penalties in the 1800s, and grave-robbing once again became lucrative business.

In the end, advancements in human embalmment necessitated by the Civil War outmoded the resurrection men. Researchers didn’t need a supply of fresh bodies when embalmment made a single cadaver usable for months.

Robert Sandeski embalms the bodies donated to Dal. As the chief technologist in the department of anatomy and neurobiology, he works with Dr. Jeffrey Scott to determine if donations are admissible to the program. When one of the tens of thousands of people on file in Brenda Armstrong’s office passes away, Sandeski and Scott inspect the body. They check for its preservability, where burns and traumatic accidents might be a factor, and for infectious diseases.

Armstrong is the administrative director of the Human Body Donation Program. She estimates that out of 300 to 400 people who intend to donate each year, only 120 applicants are accepted. The cadaver room in the Tupper Building holds up to 100. “Sometimes our facility only has so many spots, and everybody has to be properly stored. We’re not dealing with appliances where we can have a warehouse,” said Sandeski.

Wendy Simon is one of the applicants on file. The first contract she remembers signing at the age of majority was Dal’s body donation form. Her parents signed on to the program when she was a teenager.

“I was sick as a child, I’ve had different medical conditions,” she said. “I thought, maybe I’ll help them find a cure though for something I had, anything like that.” All she knew about the program back then was from her parents. She estimates that was about 60 years ago. Since then they’ve both passed away. Her mother’s death in 2011, she said, hit her very, very hard.

“Brenda [Armstrong] got me over my mother’s death – she kept me up to date, put roses on the ground on my behalf – just seeing the dignity and the respect of the whole process made me so much sure of what I was doing.” Armstrong’s job crosses between sciences program administrator and funeral home director. When someone wishes to donate their body, she’s their first point of contact. And when a family member’s body is accepted, she keeps communication open during the one to three years the process could last.

After acceptance, the body is either traditionally embalmed or goes into the clinical cadaver program. The brain Jade Panzerosa prodded as part of an undergrad lab is an example of the former. The clinical cadaver program embalms bodies to be almost indistinguishable in texture and elasticity from a live patient. These usually end up at the Halifax infirmary’s “simulation bay”, where professors like Dr. George Kovacs teach Dal medical students how it is in the real world. The simulation bay is the only one in Canada located within a working hospital. On an operating table lay a mannequin who cost $100,000. He can speak a bit with med students as they pretend to operate on him. When the sim-bay is combined with a clinical cadaver, it can increase patient safety ten-fold with the skills brought into the hands of a surgeon.

“This allows permission to fail,” said Kovacs. “You learn by making mistakes and failures.”

A poster in the room explains why students use cadavers rather than just screens and technology, which are definitely overtaking human specimens in both undergrad and post-grad schools across North America. New students entering the room must read it.

“There is no higher-fidelity simulation than one that uses the human body as a medium for learning,” the poster concludes. A text-box at the bottom reads:

The authors would like to acknowledge those who donated their bodies to the furtherance of medical science. Through their gift to the Human Body Donation Program, they have given themselves for the good of others.

“We explain to them that bodies need to be treated with the same respect as if with a live patient.” Kovacs said.

Potential donors always want to know how the bodies will be treated when they approach Brenda Armstrong – it’s one of the big concerns besides remains transportation and notification of relatives. She says there are a lot of misconceptions.

There are no meat hooks.

“The body’s are treated with the utmost respect, dignity and confidentiality. To have and examine the bodies is a privilege,” she said.

Another misunderstanding is the idea there’s a mass grave in Lower Sackville for tossing the remains.

Admittedly, this where this story originated.

The Gazette maintains a proud tradition of quality paranormal reportage, concentrated mostly around the annual Halloween issue. As I and some other editors brainstormed ideas at our offices one stormy night, a tip rang through the newswire that Dal owned a “mass grave” in Lower Sackville. This spot is a place of ghost congregation, we were told, and when one walks through it he hears small bones breaking like twigs under his shoe. We hit the million-dollar story – and scurrily uncovered the culprits: Dal’s Human Body Donation Program. While I can’t speak for everyone in the room, I will anyways: men with trench-coats, spades and oil- lanterns speaking Elizabethan English came to mind.

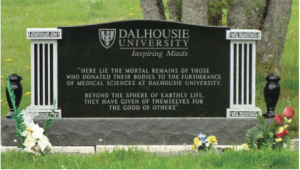

Not quite correct. After the Human Body Program is finished with a cadaver, the body is “released”. It is cremated (unless the family or estate of the deceased wishes otherwise) and often finds its final resting place at the Dalhousie Memorial Gardens, which, accurately, is located in Lower Sackville. Dal can also give or send the remains to the deceased’s estate.

It’s a “mass” grave only in the sense there are thousands of urns under the ground there.

“Everyone’s individual, it’s just one plot,” said Armstrong. “Every- body’s cremated individually, in individual urns.”

There are markers for each year of burial going back to 1978, the year the cemetery opened. Prior to that, Dal had three separate sites categorized by denomination. At the Gardens, a non- denominational sermon is given every summer for those interned that year. Six to seven hundred people attend, including students and staff from the university. The program doesn’t advertise. Armstrong says it spreads by word of mouth when individuals see the service and other aspects of the program for themselves.

Two more members of Wendy Simon’s family are now on file to donate, along with about 10 other people she knows.

“I think it’s a lot of fear of the unknown,” Simon says about why some don’t donate. “I think if more people knew what was entailed they would do it.”

Simon’s mother was interned at the Gardens after being was released from the program.

“The medical students who learned from her body will pass that down to their students. They’ll pass it on. Generations from now information learned from her body will be passed down.”