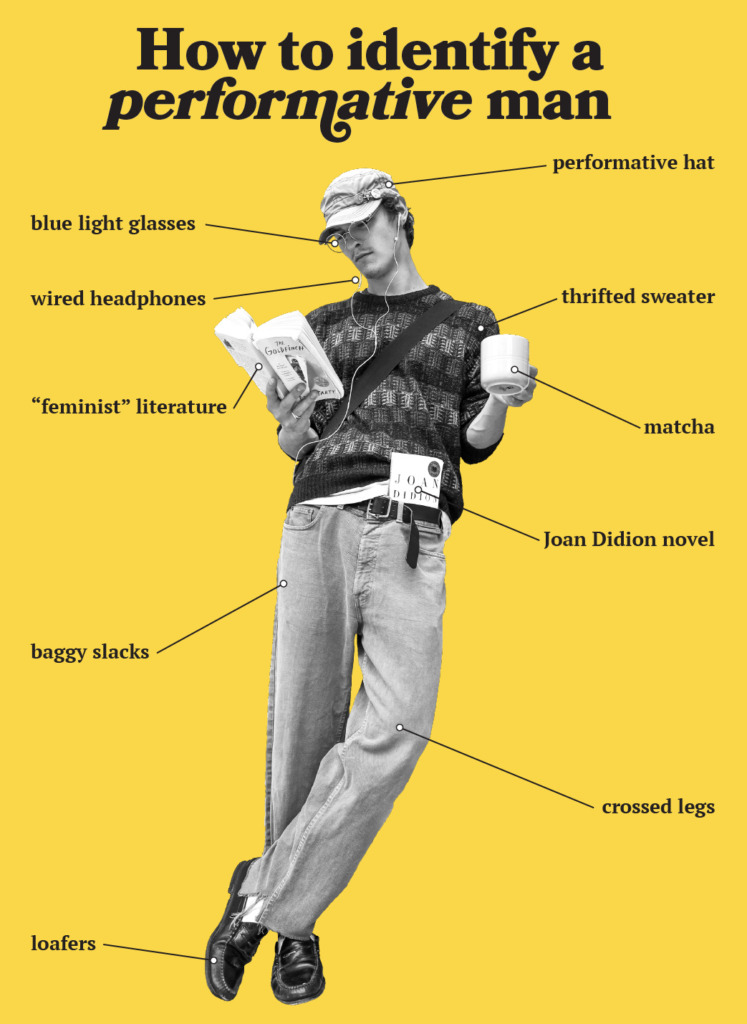

Dissecting the performative male

All masculinity is performance, these men aren’t special

In Montreal, New York City and soon Halifax, contests determine who best embodies the archetype of social media’s most recent phenomenon — the performative male. Contestants show up with wired headphones, a copy of The Bell Jar and Labubus clipped to oversized jorts as tampons spill out of their pockets for a chance to be crowned fakest attention seeker.

On stage, Mr. Performative answers a series of trivia questions about feminist history — likely answering incorrectly. The irony is undeniable, and thus he reaffirms his status as a joke.

The performative male doesn’t just exist at contests, and now men who read, have left-leaning politics and thrift are unwittingly receiving the label.

Interviewing on this topic proved difficult. Insinuating a man is a performative male feels insulting, almost like an accusation. When I approached fourth-year University of King’s College student Kieran Sabsay and asked if he thought of himself as a performative male, his friends broke into laughter. Luckily, Sabsay wasn’t offended.

“I feel like I’m what’s considered a performative male,” he says. “I kind of embody a few of those traits, whether intentionally or not.”

Blye Frank is a masculinity expert and emeritus professor at the University of British Columbia. He doesn’t think performative men are anything special.

“I don’t know that these specific things are any more performative than any other pieces of practice that all men do,” he says.

Sabsay says the trend is a positive influence that may inspire men to explore different kinds of masculinity, now made acceptable because of the viral sensation.

“A lot of guys who might not be as comfortable in their masculinity might see a trend like the performative male contest and think, ‘You know what, even though it’s kind of a joke and a silly trend, I honestly think it’s kind of cool,’” Sabsay says.

Second-year Dalhousie University student Jordan Shedden says performative men are interested in “anything sort of effeminate-leaning that is in the hopes of appeasing a woman.”

Adopting behaviours to impress a member of the preferred sex is no new phenomenon, so why are performative males only being called out now?

Najwa Mdoukh, a third-year King’s student, says, “I feel like men make fun of men. It’s always other men who are like ‘Oh, why are you drinking a matcha?’”

Sikata Banerjee is a professor of gender studies, specializing in masculinity, at the University of Victoria.

“It’s certainly possible that this criticism that [performative males] are facing is hegemonic masculinity trying to reassert itself by saying, ‘These guys aren’t serious,’” she says.

The negative reputation and memeification of the performative male may not be coincidental. Culturally, traditional or hegemonic masculinity is considered the ideal. Infamous influencers like Andrew Tate, who’s garnered a large platform by promoting patriarchal hierarchy, traditional masculinity and conservative politics, reinforces his own idealized version of masculinity.

“The only way that a true challenge to hegemonic masculinity will work is if these other models of masculinity have a true link to feminism, anti-oppression, social justice issues and challenge homophobia and transphobia,” Banerjee says.

Amelia Penney-Crocker, a third-year student at King’s, is nervous that the trend may deter young men from taking an interest in social issues.

“I really hope that the fact we all make fun of them doesn’t discourage them from reading feminist literature,” says Penney-Crocker.