The blacksmiths of Nova Scotia

Dal professor’s latest book explores vibrant provincial tradition

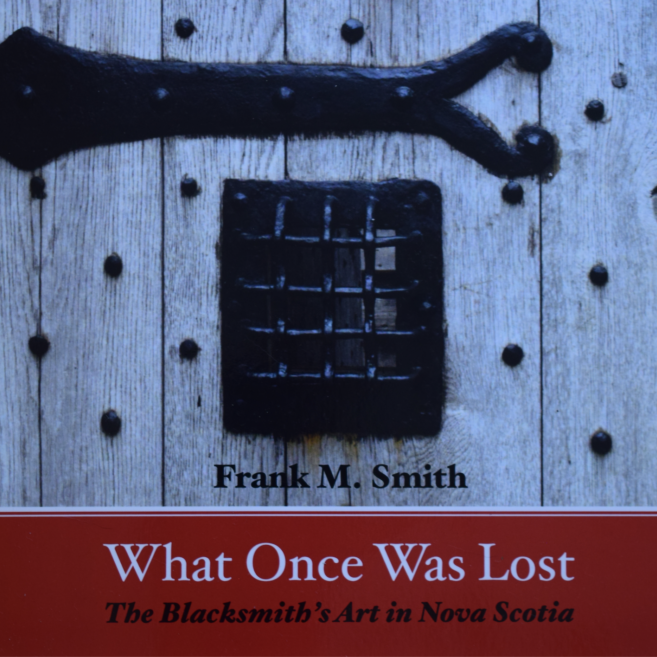

Frank Smith’s new novel What Once Was Lost: The Blacksmith’s Art in Nova Scotia refutes the idea that blacksmithing is archaic, obsolete and alive only in demonstrations by burly men at historic sites.

Discovering the community

Frank is a Dalhousie University professor of histology, a subfield of anatomy interested in the microscopic structure of tissue. He teaches in the department of medical neuroscience and researches how the nervous system affects the heart. What many of his colleagues in academia don’t know is Frank is also an amateur blacksmith.

At 12 years old, Frank watched in wonder as a blacksmith repaired his father’s pickaxe. The impression stayed in the back of his mind for nearly three decades until a working blacksmith invited him to try it on a Sunday outing to Ross Farm Museum.

“It is totally seductive once you start,” says Frank, charmed as ever even 20 years later. “Working hot metal comes the closest to, I think, total bliss as I can describe.”

Frank found blacksmiths welcoming and generous in sharing their knowledge of the craft. However, when it came to learning the local history, resources were slim and scattered. Frank aired this frustration at a dinner party in the presence of SSP Publications owner H. M. Scott Smith (no relation to Frank), who challenged him to fill the gap.

For two years Frank mined archives and visited the forges of fellow Nova Scotian blacksmiths to collect their stories. He wanted to “recreate, as it were, the Zeitgeist of the time” and showcase the relevance of contemporary blacksmithing.

Nova Scotian blacksmiths

Profiles of 14 working blacksmiths comprise the backbone of the book, each written with a narrative candour reminiscent of Ernest Hemingway. Frank laughs off this comparison, but says he did try to avoid “dry history writing.”

“This was about people doing real jobs in a real environment, so I tried to get some sort of sense of what that might be like,” he says.

As recounted by Frank, ironwork was crucial to the survival of early Nova Scotian settlements. By the middle of the 20th century, however, machines could mimic the blacksmith’s work with superior efficiency. A wave of blacksmiths closed shop and migrated towards mines, railyards and shipyards.

What Once Was Lost argues the market for handcrafted ironwork didn’t collapse under this strain, but in fact leaned into artisanal and ornamental iterations of the craft.

John Little is among the blacksmiths featured in the book whose career spans the so-called “renaissance of blacksmithing,” which began in the 1960s. Just shy of completing a master’s degree in psychology at Dalhousie, John scrapped his thesis, and turned to the land where he eventually built a shop and raised a family with his wife, Nancy. From improvising a shovel from an old oil drum to forging fishermen’s hooks to inventing one-of-a-kind instruments for musicians, he had no idea how his creativity would bloom over the years.

“Everything about this journey has had a feeling of inevitability,” John says. “It’s like I started and I just put one foot in front of the other.”

In a chance meeting with Austrian blacksmith Paul Geyer, John happened upon his greatest inspiration: a decorative blacksmith and author by the name of Edwin Roth, who’d come to work in the Annapolis Valley.

“[Geyer] opened [Roth’s] book up and I can’t begin to tell you — it was as exciting as the first hammer blow that made the metal move,” John recalls.

“All of a sudden I saw all this modern, forward-thinking, unbelievably exquisite exploratory contemporary forge work and just such imagination. You could scrape me off the ceiling for two weeks after that. I was so excited.”

John’s ironwork has been featured in national and international collections. He is a two-time finalist for the Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia Masterworks Arts Award and has received six nominations for the Portia White Prize, a provincial award for a Nova Scotian artist who has achieved mastery in their field.

A family tradition

John’s daughter is also featured in the book. Two years into her undergrad at Dalhousie, Becky Little decided blacksmithing would be her livelihood. She started out gaining experience in her father’s shop, then received an invitation to work in Germany alongside a father and son duo she met while demonstrating at her first blacksmithing conference. She worked elsewhere in Germany and Switzerland before returning to Canada.

Becky currently owns an independent shop called Dragonfly Forge in Blind Bay, N.S. With children aged 1, 5 and 7, she says it’s a challenge to spend enough time working. But one bonus to blacksmithing is just being part of a community.

“It’s kind of unique to be in a business where, in theory, you might be in competition with each other but it’s the absolute opposite. Everybody is trying to help each other out,” Becky says. “[Blacksmithing] is not only a very exciting field to work in, but. . . it kind of covers a lot of territory in terms of teaching and being part of a community.”

Becky says while demonstrating at conferences alongside people who were advanced in the craft, she started to see herself as a working blacksmith.

“[It] really made me feel like I could run with this,” she says. “Being in that room and being included in that community and in that category made me think, ‘You know, I have a place here.’”