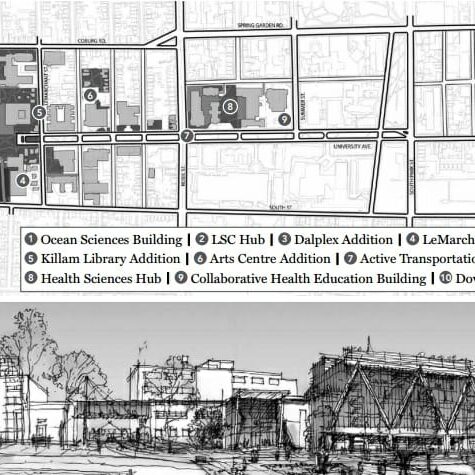

Sexton campus is badly in need of new facilities, according to students and staff. (Master Plan image via IBI Group)

With Dalhousie facing a budget crunch, the illustrations on this page might seem a bit incredulous. The university will be cutting its budget and raising tuition next year. The Gazette wondered how the university is going to pay for its future.

Bold Ambitions

“The Master Plan is a road map in terms of the direction we want to head,” says Ken Burns, vice president (finance) of Dal. “But any specific project will require the cobbling together of the finances to make it work.”

Burt is one of the planners behind Dal’s Master Plan, a set of documents outlining development of “unprecedented magnitude” to take place between 2010 and 2020.

Dal is constantly ‘cobbling together’ millions of dollars to repair buildings and update facilities to modern standards. Burn says his own office holds 20 per cent more people in the same space than it once did, and is cheaper to operate. It also no longer resembles a classroom.

But the university isn’t just getting older—it’s growing. And there are a number of landmark projects in the works.

Capital

Dal has spent over $100 million on new buildings in the past five years, and you can see (and take class in) the results: the Mona Campbell on Studley Campus, and the Life Sciences Research Institute on the Carleton campus, for example.

Even more construction can seem gratuitous when the university faces financial pressure, but Burt says it’s necessary.

“Dalhousie has a very, very old building stock. Most of our buildings are between 30 and 50 years of age, and that’s about the time that buildings begin to fail,” says Burt.

The university is currently spending a little more than half of the estimated $30 million per year required to keep its facilities in shape. The university’s deferred maintenance—the total cost of returning all of the buildings on campus to their original condition—is currently estimated to be $280 million, nearly 85 per cent of the university’s operating budget.

“We’re playing catch-up right now,” says Burt.

Rodents, asbestos, poor lighting and leaky roofs are just a few of the problems facing Dal. The most pressing issue is space: the university needs fewer small classrooms, and more large lecture theatres, says Burt. And the problem is most acute on Sexton campus.

When Dal merged with the Technical University of Nova Scotia in the late 90s, it inherited a campus in disrepair. “We’re spending about a third of our deferred maintenance on that campus alone every year, just because they’re so far behind,” says Burt.

The university is planning to remedy the situation by building a new complex—the IDEA, or ‘Innovation and Design in Engineering and Architecture,’ building. The proposed facility will be home to the booming faculties of engineering and architecture & planning.

Elizabeth Croteau is the president of the Dalhousie Undergraduate Engineering Society (DUES).

“We’re looking at an 87 per cent increase in the number of students on this campus,” says Croteau.

“While we’ve been used to having between 500 to 600 people on campus per semester, some new changes to the curriculum mean that two years from now there’ll be 1,000 people on Sexton, in engineering. Which is an absolutely ludicrous number considering how jam-packed we are down here already.”

Burt agrees. “They badly need new space on the Sexton campus,” he says. Currently, second-year students have to take classes in a theatre in Park Lane mall—and the university has to pay Empire Theatres for the privilege.

Joshua Leon, dean of the faculty of engineering, says the faculty has been planning the building for years. They are using projects at Concordia, Queen’s, and Ecolé Polytechnique as models

“We’re looking at a state-of-the-art building,” says Leon. “Dal students deserve it.”

How to pay for it

Projects like IDEA are expensive. Leon estimates that the IDEA building will cost between $18 and $30 million dollars. But the money from construction doesn’t necessarily come out of the university’s operating budget.

Some facilities, notably residences, are effectively free to the university provided they are used. Residence fees pay for the construction cost over time.

But for other facilities, such as labs and classrooms, it’s more complicated. Burt says that the university pays for about one third of the cost of any new facility. The rest comes from donors, and from support from some level of the government.

For example, the Mona Campbell building on Coburg Road was partly funded by a $10-million bequest by Mona Campbell as well as a grant from the provincial government intended to help cover maintenance costs.

But Burt says that Dal doesn’t have access to the same level of government support as other large universities in Ontario, British Columbia or Quebec, which will sometimes pay for facilities outright.

“Pick any one,” says Burt. “The governments of those provinces either provide full funding, or they provide incentives to the funding, where they match the money universities put up for new construction.”

For the IDEA project, the university is pursuing one traditional source of funding: a generous donation. The IDEA facility is listed as a $20-million “Opportunity for Support” on the website for Dal’s ‘Bold Ambitions’ fundraising campaign.

The ‘Bold Ambitions’ campaign currently stands at $200 million, with a goal of $250 million. Leon says that a number of donors have already committed money, but not enough to break ground.

“If someone came and wrote a cheque for $5 million tomorrow, I think we’d see it built very quickly,” he says. “Optimistically, I’d say three years.”

But the university isn’t relying on donors alone. Without strong government support or room in the operating budget, the university has turned to a different source to fund the IDEA building: an auxiliary fee, levied on engineering students.

Auxiliary fees

The faculty of engineering approached the students earlier this year. Corteau says DUES was asked whether they thought the student body wanted new space enough to be willing to pay a fee of $75 to $100 a semester for it. Leon estimates that this fee will finance a quarter to an eighth of project.

The DUES executive was unanimously in support of the new fee, says Corteau, “provided a few conditions were met.” The society wanted student representation on the planning committee and a guarantee that the fee wouldn’t go into effect until the building opens.

“DUES really wants to see student space on this campus that is useful and effective. We’re willing to pay to have our say in that,” say Corteau. “And we also want it to be relatively timely.”

The proposed IDEA fee isn’t novel. In fact, the IDEA building will be the second new construction project funded by a direct levy on students. The new athletics facility on Studley campus will cost Dal and University of King’s College students an additional $90 per semester when it opens. The Dalhousie Student Union (DSU) council approved the fee in 2010.

Tuition versus fees

Under the memorandum of understanding (MOU) signed by the university and the province in 2009, tuition increases are capped at three per cent per year for undergraduates. Auxiliary fees, although the province must approve them, are not similarly capped.

If both the new athletics fee and the proposed IDEA fee were to be in place next year, engineering students would face a 6.5 per cent total fee increase.

Despite the fee increase, DUES student council approved the new IDEA fee 17-4, provided their conditions were met.

“I personally would be willing to pay $75 right now if it meant I got a bunch more student space, a bunch more bookable design rooms, and my poor satellite design team out of a non-existent corner of a lab,” says Corteau.

Reactions

While some students are worried about the prospect of paying even more to the university, others are more ambivalent. Those in their second, third or fourth year likely won’t be around by the time the fee is put in place.

Sarah Martakoush is a first-year engineering student and is a first-year representative for DUES. She voted for the proposed fee.

“I want lots of space,” says Martakoush. “I don’t want to walk around to Park Lane theatre for class.”

Despite DUES’s support for the fee, there is a certain element of pragmatism.

“If they decide to tack on a levy, we can’t really stop them. This way, at least, we’re having the levy implemented on our terms, rather than hidden elsewhere—rather than having a ‘Sexton Campus Fee,’” says Corteau.

“We think that more people four or five years down the line will thank us, than curse us.”