Internalized Capitalism

How economic systems have created our mania for productivity

As the clock marks the passing of yet another hour, you feel your glasses slipping from the bridge of your nose. The room smells like cheap burnt coffee and work papers are scattered around the table like an ugly mosaic. Sitting in what is probably a bad posture for your back, you tell yourself it’s a one-time thing. It is finals season. You’re only staying up this late for an important assignment! Rubbing your eyes, you know you must go bed before exhaustion overwhelms you. But you can’t.

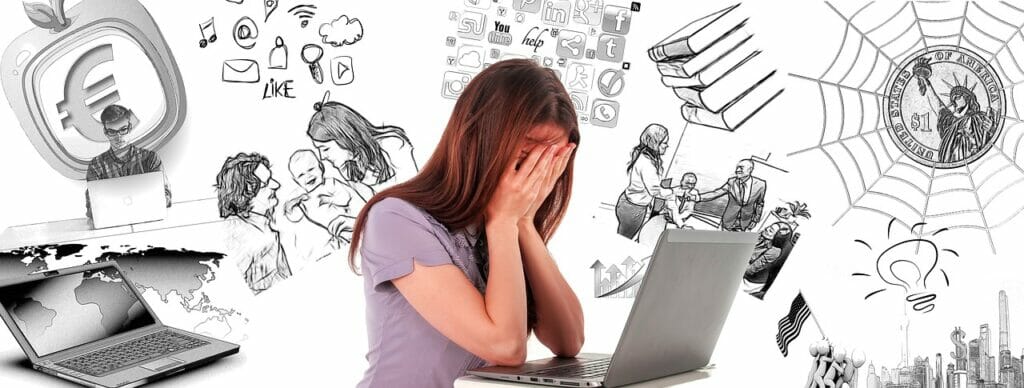

If this scenario sounds startlingly familiar, it’s likely you have unknowingly experienced something called internalized capitalism.

What is internalized capitalism?

Perhaps the idea of not being productive or smart enough haunts you. Thus, you work and work until you feel you deserve a break, thinking it’s normal to exhaust yourself at work and feeling guilty for taking rests. It stops being an issue as hours of deep anxiety become meaningless under the shining success of finishing an assignment. Little by little, such moments ease their way into your weekly routine until you no longer question them at all.

This scenario and the negative thoughts of self-hatred that accompany it are symptoms of internalized capitalism. Although the term has not been approved by any official dictionary, its popularity continues on platforms such as Instagram and Twitter. As the The Cornell Daily Sun explains, “Under capitalism, individuals are forced to maximize productivity and beat out competitors.” This culture of forced productivity leads to an “environment of competition and self-imposed stress that today’s youth has grown up immersed in.”

“Internalized capitalism fundamentally suggests that individuals grow to equate their productivity with their self-worth.”

Internalized capitalism suggests individuals grow to equate their productivity with their self-worth. This can lead to harmful ideas about how to be successful: late-night study sessions, self-imposed stress, sacrificing healthy eating, neglecting sleep, daily unachievable work goals and more.

The impact

This is by no means a new phenomenon: Capitalism has burnt millions of members of the working class numerous times before. In fact, humans’ fixation with productivity in workspaces has grown to be so tremendous in countries like Japan where people are known to die from various conditions related to overworking. This phenomenon of death by overwork is called karoshi. In 2019, there were 1,949 suicides in Japan related to work problems.

Singapore, for example, is glorified as a technologically savvy and wealthy city-state. But its population has an average of 44.6 working hours per week, which stands in contrast with countries such as Sweden and their weekly average of 30.9 hours. The question about reducing work hours is something that’s even present at a local level. In June, 2020, the Nova Scotian municipality of Guysborough started a nine-month pilot plan to reduce work days from five to four a week. Hence, allowing the working class to prioritize rest and relaxation in a productivity-driven society.

Regardless, frantic and unpleasant work is something that’s truly become characteristic of our culture. We’ve romanticized internalized capitalism and downplayed its harm.

Reimagining productivity

Are we truly defined by the work accomplished every day? Is our success only measured by sleepless work? Must we fill each day in the calendar with a work quota to make room for a free weekend? Internalized capitalism has several ramifications. If self-worth relies solely on achievements and production, self-love is conditional, doomed to rely on the next big success or the next due date for a work project.

Anders Hayden, a political science professor at Dalhousie University, says “there are a lot of parallels between academic life and internalized capitalism.”

“We need to produce something to have a sense of value. Hopefully, it’s successful. But can we rest on our sense of success? No. You need to be productive again to have a sense of self-worth. In terms of academic work, you internalize that as well,” Hayden says.

In 2020, there has been a 300 per cent increase since February in people searching “how to get your brain to focus” on Google. This may be a question many university students and professors are asking themselves as they try to be productive during the school year amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

As Hayden says, academics are feeling a “constant sense [they] need to continue pushing to do more to get those publications out” and there is “no time to sit and rest.”

There may be great worth in re-evaluating our school or workplace habits and values. By refocusing our goals beyond daily achievements, we may be able to regain an inner peace that the cycle of production of capitalism doesn’t provide.