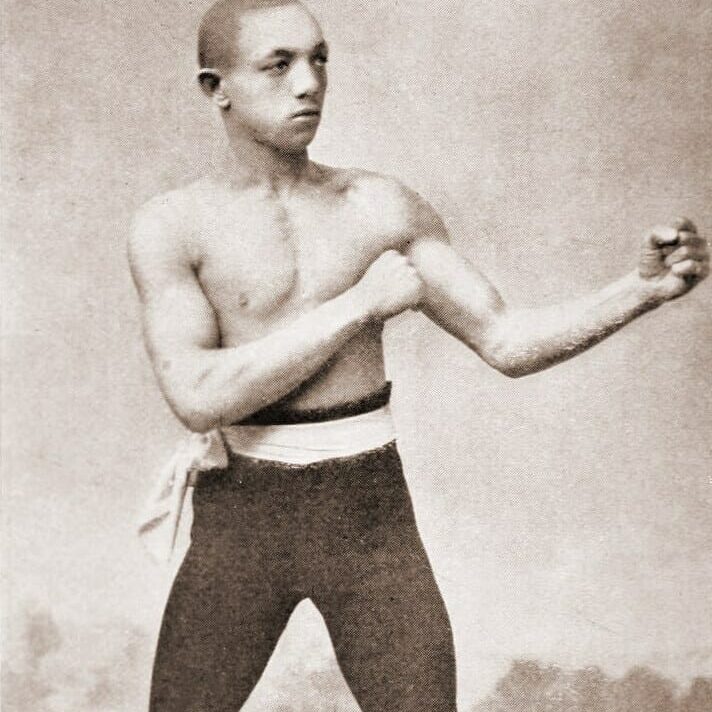

Nova Scotia boxing legend fought not only opponents in the ring, but discrimination

A homage to one of the greatest boxers of all time, almost 152 years after his birth

60 years before Jackie Robinson debuted for the Brooklyn Dodgers and 70 before Willie O’Ree signed with the Boston Bruins, Halifax native and boxing legend George Dixon was establishing himself as one of the greatest Black athletes and lightweight fighters of all time.

Born in Africville in 1870, Dixon’s career began at the age of 16, winning his first fight by knockout in the bantamweight division. He stood just five-foot-three and weighed 87 pounds.

Just two years later, fighting primarily out of Boston, he won what was considered in the United States to be the world bantamweight title. Lack of international structure in 19th century prizefighting lead to this claim being contested by some, including “Nunc” Wallace of England.

To settle this, Dixon travelled to England in the summer of 1890 where he defeated Wallace by knockout after 18 rounds, making him the undisputed bantamweight world champion, as well as the first Black and Canadian world champion. The fight itself is still highly regarded in the sport today.

Shortly after defeating Wallace, Dixon increased his weight to 115 pounds and began fighting in the featherweight class. He would win the world championship in 1891 and defend that title for most of the next decade.

Facing discrimination

Such success in a sport dominated by white athletes, managers and organizers subjected Dixon to discrimination over the course of his career, particularly in the American South. In 1892, at the Carnival of Champions held in New Orleans, La., Dixon refused to fight unless Black supporters were allowed in the venue.

He convinced organizers to reserve 700 seats for local Black spectators in a separate section upstairs in the venue, although still a small proportion of the 50,000 seats sold that weekend. Though the Carnival of Champions was by far the most notorious instance, by this point in his career Dixon would regularly demand Black spectators have access to tickets for his fights.

Reports have said he used his fame to create opportunities for other Black boxers. He was also “known” for contributing much of his earnings to Black communities such as Africville.

Likewise, he was known for his stamina and endurance. Dixon’s fight would often last lengths unheard of by any modern standards. On multiple occasions, Dixon was recorded fighting upwards of 40 rounds. Once, he went 70 rounds fighting for the American featherweight title. One of the longest matches ever recorded, this bout lasted over four hours. This supernatural stamina was tested during numerous exhibitions and regional tours that he and many other 19th century professional athletes relied on to keep the cash flowing.

Some argue it was Dixon’s management who was prioritizing his exhibition fights. By the later part of his career, he was fighting so regularly that many in the professional boxing world predicted his premature demise. Dixon’s party would arrive in a town, and his manager would offer any local amateur a cash prize if they could last more than 3 rounds with Dixon. On some tours, Dixon was reportedly fighting upwards of 20 fighters a week, meaning multiple bouts each night.

Because of this, it’s impossible to determine Dixon’s precise career win-loss record or to discern which fights were professional. His manager claimed to have arranged upwards of 800 fights over his two-decade career, though other sources say he fought in fewer.

In any case, Dixon’s signature quickness and durability began to fade, and with it his fame. Many have said that Dixon was shielded from the worst of the racial abuse and discrimination felt by Black people in America by his wealth and fame at the height of his career, but if so, it did not last.

As his career came to an end, Dixon, once thought to be the wealthiest Black man in North America, died with almost nothing in the streets of New York in 1908. He had struggled with alcoholism in his later years, as his death came just two years after his last professional fight.

While he was left behind by the prizefighting world after his skills and fame began to fade, he is recognized widely as an iconic fighter and personality. Dixon was enshrined in the Canadian Sports Hall of Fame in 1955 and was part of the inaugural class of the Nova Scotian Sports Hall of Fame in 1966. He also has a community centre named in his honour between Gottingen and Brunswick Streets in Halifax.

Perhaps his most significant honour came in 1990 — 100 years after he travelled to England to prove his world dominance — when he was finally inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame, where his legacy of a distinguished fighter of world-class opponents and discrimination lives on.