Everything’s a gamble

The all-encompassing world of online gambling

Scott Easson started gambling online in Grade 11. A long-time sports fan, sports betting was a way to make money off something he was passionate about.

“I can make some bets with my buddies, watch a game and add extra stakes to it,” he said.

Easson, now a first-year management student at Dalhousie University, still gambles, mainly on sports. It’s standard practice for him to place a bet while watching a game with friends.

For many young people today, online gambling is accepted and normalized, comparable to other vices like drinking or smoking. The difference is that young people today are actually drinking and smoking less than ever before. As these traditional youths’ revelries have declined, online gambling has exploded.

Roughly one in three Canadians aged 18 to 29 gambles online, according to a November 2025 study from the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA). Only one in 10 young Canadians engages in traditional lottery gambling.

Online gambling offers a more accessible and addictive way to bet. Nearly 70 per cent of young online gamblers showed signs of problem gambling — almost 14 times higher than young lottery players.

Easson says online gambling is popular and “normalized” amongst his friends, but online gambling, at least in Canada, is a relatively new phenomenon. Gambling was provincially regulated until a 2021 federal law legalized single-event sports betting, followed by a 2022 Ontario law that opened the market to private online gambling companies, fueling its meteoric rise.

Matthew Young, a Carleton University psychology professor and author of the CCSA study, says online gambling is popular among young people partly because of its convenience.

“Historically, if you wanted to gamble, you had to get up, get dressed, leave your house and go somewhere,” he says. “Now, you don’t have to leave your room.”

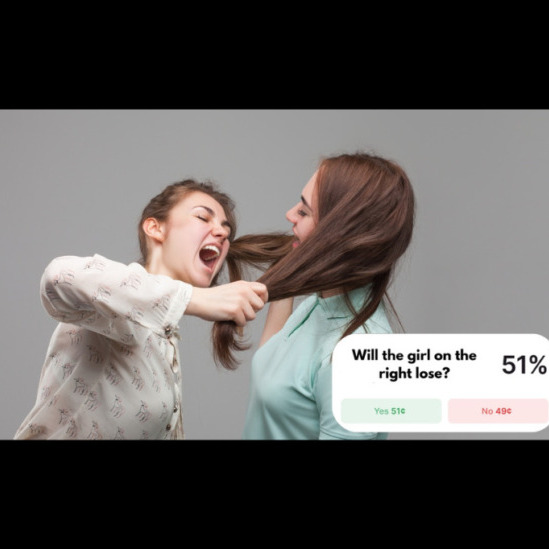

One form of betting making headlines is prediction market gambling. These markets function similarly to sports betting, but allow users to bet on anything, including international events. On U.S.-based sites like Polymarket and Kalshi, users can bet who will be the next president of the United States, whether Israel will attack Gaza on a given day or whether the second coming of Jesus Christ will happen before 2027 (three per cent of Polymarket bettors say yes).

This kind of gambling offers an illusion of skill, the idea that bets aren’t gambles, but rather based on knowledge of international affairs.

While cigarettes and cannabis advertising is almost entirely banned in Canada, and alcohol advertising has restrictions, Young says similar rules don’t exist for gambling.

“It’s just nothing. Full stop,” he says.

In 2024, CBC Marketplace and researchers at the University of Bristol found that gambling advertisements make up about 21 per cent of Canadian sports broadcasts. Eleven of the 20 Premier League soccer teams have gambling sponsors emblazoned across their chests. Easson says he sees gambling ads “all the time.”

Gambling is different from other addictions, because when buying a beer or pack of cigarettes, there’s no chance that the purchase could make consumers their money back.

“It’s theoretically possible that doing more gambling can get you out of the hole you’ve dug for yourself through gambling,” says Young. “Theoretically possible, highly improbable.”

One factor that could be to blame for young people’s propensity for online gambling: economic nihilism. An Ipsos survey found that 80 per cent of Gen Z Canadians think owning a home is “only for the rich,” and a GreenShield survey found 76 per cent believe that “no matter how hard they work, larger forces beyond their control will determine their financial future.” When young people feel that no amount of financial planning will help them achieve their financial goals — or think they can only afford a house if they win the lottery — there’s no reason not to gamble.

Why not try to win if there’s nothing to lose?