Driving through the dark

Something rare just happened and everyone knows it

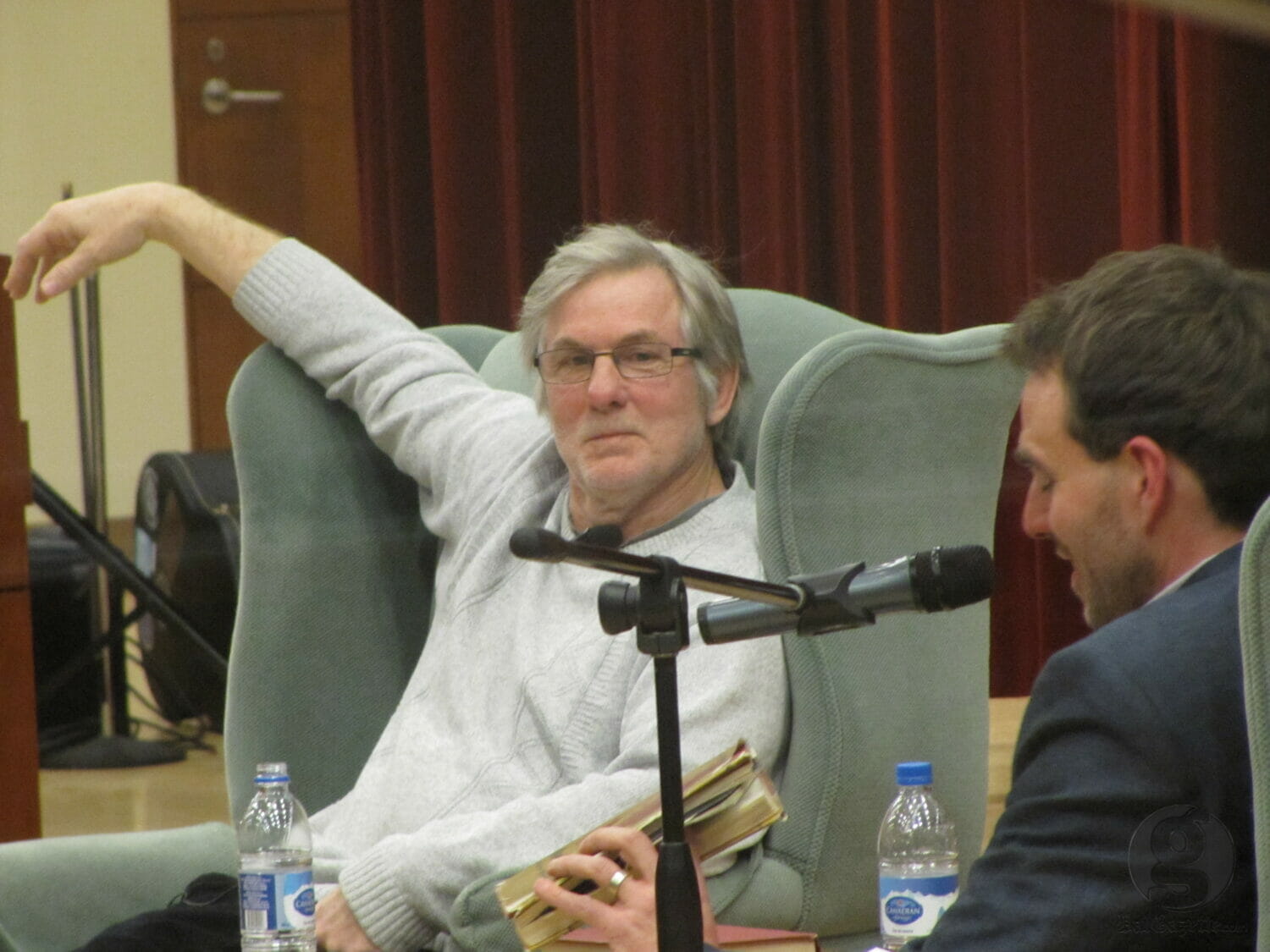

Something rare just happened and everyone knows it: the guy holding back tears and writing in his notepad knows it– even the lady asking David Adams Richards an absurdly personal and fawning non-question about her love for his writing knows it. This is the first time Richards has read from his 1976 novel Blood Ties in decades.

The New Brunswick author reads 12 pages from his second novel to a packed and reverent crowd Friday at Saint Mary’s University McNally Theater for the Cyril J Byrne lecture. And 12 pages is enough to knock the room flat with the novelist’s typically understated emotional power, before he sits down to speak and field questions with SMU professor and fellow Can-lit heavyweight, Alexander MacLeod.

The passage from Blood Ties, a book he wrote at the age of 25, traces the heartrending courage of a rejected marriage proposal– a scene Richards prefaces by saying, “It’s a doomed love, but he can’t help it.” The passage has the typical Richards themes of fate, self-delusion, humour and tragedy. These ideas are writ small between images of Miramichi life, where characters bound by blood, place and complex history offer disarming dialogue against Richards’ mysterious backdrop of cosmic darkness.

For all its pastoral romanticism, Richards early work has the kind of flaws which, both author and audience know, should be celebrated. “I used to be more lyrical when I wrote Blood Ties” he says, “but, now [in my books], I’m more analytic.”

An audience member mentions how Richards illuminated the parallels between the Southern states and the Maritimes, and MacLeod suggests he talk more about the Southern and Russian authors.

Richards acknowledges a debt to the searing moralists to whom he’s often compared, Flannery O’Connor and William Faulkner. But it’s another existentialist from an earlier century with whom he most relates.

“Dostoevsky is one of my favourite prophets. He had real problems– as crazy as a bat in a bottle, but he’s one of my favourite prophets,” says Richards, who gets under the skin and heart tissues of alienated outsiders as well as any contemporary writer.

The recurring image of the evening is one of driving at night, introduced in MacLeod’s opening remarks as an apt image both for Richard’s writing, and his actual journey across the dreaded Cobequid pass to make it to Halifax on the snowy Friday evening.

E.L. Doctorow famously said, “Writing is like driving at night in the fog. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.” Richards’ career, spanning 26 books, has seen many of his recurring characters navigate through the common tragedies of life with moral courage in a seemingly callous universe.

A gritty, open-ended lyricism has always been the operative mode for Richards. He’s tried his hand at more philosophical thought in recent years, such as the 2009 collection of essays God Is, an exploration of faith in the context of an increasingly nihilistic and amoral literary world. Richards, one of three Canadians honoured with a Governor General’s award for both fiction and non-fiction, isn’t slowing down, but the retrospective moment on Friday felt like a good resting point under the lights along a long, dark roadway.

Maybe MacLeod sums it up best in his introduction to Richards’ work.

“I have always maintained that David Adams Richards has devoted his entire career and in a very tangible way, a serious proportion of his life’s force, to writing just one book, not the 26 we have now,” he says.

“We are reliably returned, time and again, to the same abiding concern for the emotional and ethical integrity that every individual has to struggle for with their choices and the same sympathetic, but clear eyed cataloging of all the consequences– the sometimes joyful, sometimes hilarious, sometimes tragic and sometimes brutal consequences– that flow on from every one of those decisions.”