E-readers are good for students. They are also good for people who travel a lot, whether they’re commuting or sitting around in airports a lot. And they are great for people who have large libraries but very limited housing. (To quote the genie from Aladdin, “Infinite cosmic power—itty bitty living space.”) And yet despite fulfilling all three of these requirements, I can’t help but detest them. Maybe that makes me old-fashioned and two years out of date, but book culture and technology have always been slightly slower to move and I’m clinging to the past.

As a student who loves to read, I have two libraries. The first is at my parents’ house, a mad collection of books propped haphazardly on shelves I put up myself when I ran out of room on the five shelf bookcase my parents had thought would suffice. I’ve got books in boxes, stacked underneath my desk, and likely hidden under my bed. The second library is here in Halifax, where I have most of my academic books and a lot of books for recreational reading which I constantly tell myself “yes, I’ll get around to reading this weekend,” and never quite seem to find the time to read. There is also a third library, which as a bibliophile I don’t like talk about. My e-book library.

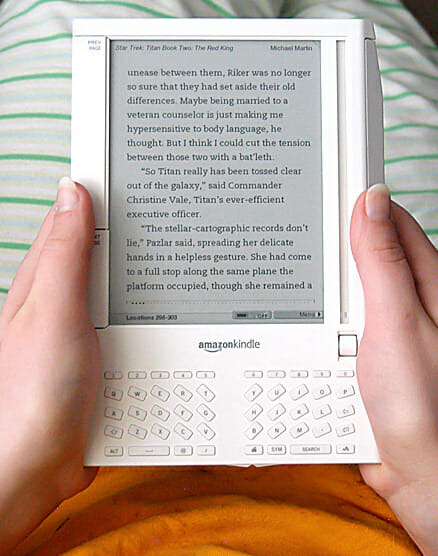

I am the ashamed owner of an e-reader. In an effort to curb my spending on books, I purchased one a year and a half ago, and it has remained largely unused since. I suffer through the heavy back packs and strange looks – why? E-books are cheaper, more convenient, says the rhetoric. E-books will soon replace real books, and you’ll be left a dinosaur of a great, 500-year-old history. Or so they say. But “they” are fed by the advertisements of the e-reader giants, and aren’t quite aware of what they’re buying into when they’re buying an e-reader.

The economics of e-books aren’t great. E-books are not cheap. That is a common misconception. I’ve seen e-books more expensive than their paperback copies. The cheapest e-books are bargain bin e-books—buy at your own risk! E-readers are possibly only good if you find yourself purchasing a lot of content that’s available on the public domain (e.g. Project Gutenberg). But more than that, e-books are a digital format. This means if your e-reader breaks while you’re on vacation, no books. Your computer crashes? No books. Amazon’s servers crash and erase your purchasing history? No books. It’s much easier to lose the entirety of your library in an instant in a code error, and we’re too blinded by technological optimism to see it.

Even worse than that, the publishing industry is capitalising on our culture’s love of sharing and enjoying what we read. Want to lend a friend a book? That’s a bit more difficult if you have an e-book. Want to get it second-hand? Good luck. And, in a surprise twist, books then get torrented in an effort to subvert this system. As with all digital media that is a tricky issue, but it is a lot more fragile in the literary industry when an author’s success depends on their revenue.

Physical books hold memories. They show wear and tear, dog ears and tea stains, and smell both wonderful and strange. You can get to know a person by their books and the way they treat them, by the books that are the most dog-eared and bent at the spines, versus those that look almost new, meticulously well-cared for. You can’t replicate this experience with e-books, and that’s what reading truly is: an experience.