“Mostly, they had to forget that they had not come up with a way to leave. They had to think that one might present itself if they waited long enough. Why should they think about the future? No one else seemed to remember it.” –Ann Patchett, Bel Canto

A light rain was falling on lower Manhattan when Jamie Arron stepped into Liberty Plaza. Zuccotti Park was a warren, a nest, a solid wall of tents and tarps and signs dripping in the rain. If the train of students following Jamie felt small carrying their packs and sleeping bags through the giant neon lights of Soho and Tribeca and the towering cliffs of the financial district, they felt smaller now. They were one tribe, far from home, standing at the edge of the chaos of the park.

A tattered marching band with a trombone and a fiddle and a drum appeared out of the rain and oompahed past, followed by shouts and cheers. Despite the rain, there was a festive atmosphere at night. The roar of drums from the west side of the plaza ricocheted off the skyscrapers and enveloped the park.

The inside of Zuccotti Park was dark—there was no electricity—and there were only narrow paths between the tents. Every available corner was packed with canvas, and the few bare trees were covered with spider webs of rope.

The city of tents, dark and massive in the rain and darkness, would only survive four more days before the New York Police Department would sweep it out of existence. “No one knew it, but Jamie and the 37 travellers with him were about to see the last days of the occupation.”

“You’re welcome to stay here,” a woman with a tattooed throat told Jamie when he found the information centre, “but it’s tight finding space for tents.”

*****

The travellers had woken up that morning, bleary eyed, to the swish of rain on the windshield of the bus. One Burger King croissant went mostly uneaten at the Kennebunk turnpike, but two Starbucks sugar shakers were emptied into cups of coffee.

Matt Burton had got on the bus in Moncton, and was perched up on his seat wearing a leather jacket and a Guy Fawkes mask cocked back on his forehead. As the bus passed through an endless tunnel of brown poplar trees, he delivered a monologue to whoever was listening.

“There are problems with the SYSTEM. The ARTS aren’t valued by our economic SYSTEM, and Stephen HARPER is cutting some, some two BILLION from the ARTS.”

Everyone was talking politics of some kind. Hamish Russell was talking about socialism in the seat behind Matt. He came to Canada from New Zealand and ended up living on the Grand Parade in Halifax. He does not call himself a socialist, but he says the current form of capitalism must go.

Stefi van Wijk was half listening to Matt and half studying Plato. She is in first year, but her earnest intensity has already put her in a role of leadership. Like Jamie, when she speaks, people listen.

As the bus rolled through the New Jersey turnpike, Matt was still in his monologue.

“YOU can also BE a corporate IDENTITY. But if you are a natural PERSON then laws can’t DEAL with you.”

*****

Jamie had decided he wanted to go to Wall Street 10 days earlier. He called his friend Kat Stein and told her.

I’ll put down the money, he said, let’s make this happen.

Less than a week later, he had upgraded from a 29 seater bus to a 36, and then again to a 42. He had already made back three quarters of the $8,000 of his own money that he had spent. And the list was still growing.

Jamie insisted that he did not want to be the leader, that everyone was coming on their own terms, and that he could not make decisions for other people. But when he met with 30 other students in the Dalhousie Student Union Building, they listened in silence as he told them about the risks of crossing the border and of protesting in a country where they had no legal protection.

“We don’t really know the situation that we’re entering into,” he said. “It could change at any moment.”

And change it has. It is Friday morning, and the sun slanting over Broadway finds a smear of brightly coloured tents slapped across the cold stone face of Manhattan. The tribe wakes and shivers, and tries not to feel naked and exposed as the downtown morning rush stares up at them on the steps of Saint Peter’s Church. They found refuge here when Zuccotti Park proved too full to hold 30 Canadian university students.

Beside the old World Trade Centre site, the digital thermometer reads 47 degrees (8 C), but the wind cuts much colder.

The rain has stopped and spirits are high in Zuccotti. Drums are echoing off the black facade of 1 Liberty Plaza, and the smell of toasted bagels floats from the food tent. The mood is optimistic. In the morning, under a blue sky, with the green peace flag flapping over the park, it is easy to imagine that this will last forever. Zuccotti is its own city, with its own library, its own traditions and geography. Even the cops on the street do not seem threatening to the canvas and plastic edifice of the park.

*****

There are no police officers in New York. There are only cops. Even the orange ticker in the subway tells you if you see a suspicious package left unattended you should immediately inform a cop. Not a policeman. Not the authorities. A cop.

The cops stand around the park every 15 feet, playing an endless game of shuffle-it-along. Stand still too long on the sidewalk, and a cop tells you to keep moving because you’re blocking traffic.

It is not because anybody is blocking traffic; there is plenty of space on the sidewalk.

The cops say this because once one person stops to stare, another will stop. Like a clogged blood vessel, people begin to coagulate into a mass of talking, shouting, laughing, sign waving humanity. Before the cops can lift a gloved finger, the mass is bulging out of Zuccotti Park and spurting protesters out onto the street.

Stefi plays a round of shuffle-it-along with a cop called Markov, because she is trying to guard a pile of tents and sleeping bags.

“You gotta move off the sidewalk,” Markov tells her. “The sidewalk is public space.”

“Yeah, well, this is all public space, right?“ Stefi says.

“Look, just move off the sidewalk,” Markov says with a false-sweet New York yaw in his A’s.

Stefi turns and squares herself. She has three inches on the little moustached cop, and her Dutch blood shows in her square shoulders and firm jaw.

“Yeah well, I’m just asking.” Stefi says.

Markov drops the sweet voice, and tells her to get off the sidewalk. For a moment, Stefi doesn’t move. Everyone is looking now—two other cops, the girl knitting a hat in her deck chair, the guy selling “99%” buttons. She doesn’t move, and for a moment Markov puts his hand on the guardrail, like he’s going to walk onto the sidewalk.

Kat Stein grabs Stefi’s shoulder, which is barely below her nose, and says “He’s just saying, stay over here.”

The spell is broken, and Stefi turns away. Nobody is going to be arrested this time.

*****

It is Friday night when news trickles in that Occupy Nova Scotia is gone. The tribe is sitting in a panini shop next to Zuccotti, drinking tea to keep the management happy, and passing around an iPhone showing video of the eviction.

“In the middle of the night…”

“… In Secret?”

“Oh my god…”

“That’s heavy…”

Hamish Russell makes the announcement that everyone already knows solemnly. “They dragged them through the mud to jail. There is no more Occupy Halifax.”

Hamish is the only true occupier of the Dalhousie tribe. He lived on the Grand Parade for two weeks, emptying and refilling dishwater with quiet perseverance, and going to his Dalhousie classes. The others have lost a movement, but Hamish has lost his home—temporary though it was.

In Zuccotti Park, tension is growing. The anarchists have been handing out pamphlets for a general assembly tonight, when none was scheduled. There is talk of “taking back Zuccotti Park from the bureaucrats,” and fighting the “1 per cent of Liberty Plaza.”

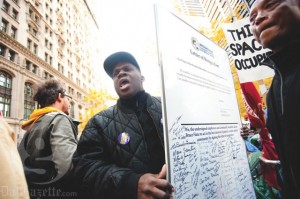

When the assembly gathers, the crowd is tense and restless. The human mic—the assembly which repeats back a speaker’s words in amplifying unison—is unsteady and cacophonous. Each speaker sets the crowd into grumbling and whispering. They talk about closed meetings, the executive spokes council which has claimed too much power, elitism, and retaining the values of the movement.

One facilitator mentions—perhaps carelessly—that this assembly is not the “official” assembly of Occupy Wall Street. An excited anarchist makes him sit down, and they have a whispered argument full of angry gestures.

“Point of process,” a man yells from the crowd. Before he can go on, he is cut off by another caller who is more successful in gaining the support of the human mic.

“Point of process (point of process!)” the second speaker yells.

Danielle Howe was not at the unauthorized general assembly. She went to a meeting of the 50 working groups which have branched off from the original assembly. The meeting was intended to ratify the working groups. Only two were ratified. The rest of the meeting was spent arguing over whether or not the meeting should continue when not all members were present.

That night, Jamie and Danielle watch a prayer circle at night in Central Park. Matt is there too, with his Guy Fawkes mask on this time, and gives a rambling prayer to mother earth. The cops stand on the sidelines, the headlights of their cruisers lighting up the huddled circle of protesters.

“Oranika, orai, nika nika, hei hei, riki tai-tai,” the protesters sing.

Nobody mentions that this circle will end in arrests. Maybe the silence is for the sake of the police. Maybe it is for themselves.

Jamie and Danielle leave quietly before the evening curfew, when the police are sure to swoop down on the remaining protesters. The tribe has made a pact: nobody is to get themselves arrested.

*****

The first rays of sunlight do not reach the steps of Saint Peter’s until mid Saturday morning. First, the sun must climb its way over the gothic shoulders of the Woolworth Building—the cathedral of commerce itself. The terracotta gargoyles and green copper roofs thrust 57 storeys above the huddle of protesters in Zuccotti Park, above the seven little tents on the steps of Saint Peter’s, and the five police vans that are parked at the church steps.

Stefi and J.D. are the first out of their tents. They stand frozen for a moment, staring at the police. They eye the vans, and the officers with their swinging nightsticks, and two police buses parked up the street. Buses mean arrests—it was likely a bus like these that took away eight protesters from Central Park the night before.

Nevertheless, the tribe packs up camp with one eye on the cops. Voices are hushed and eyes downcast until they have shuffled back to Zuccotti.

“What are they doing?” laughs a New Yorker on his way by the church, “Occupying religion?”

The regular general assembly of Occupy Wall Street is held that night. It is bizarre but awe-inspiring. The south-east corner of the park is packed, and the collective voice of the assembly reaches the far corners of Liberty Plaza.

The topic of the evening is whether or not the movement should take out a copyright on “Occupy Wall Street.” Sam Cohen, a lawyer who volunteers to represent the assembly, stands awkwardly in front of the crowd and tries to explain copyright law. The assembly reacts with confusion and anger. Nothing is accomplished. The argument drags on for four and a half hours. Voices go hoarse, heads ache, and the crowd shrinks to a quarter of its size.

It would be the last general assembly held in the occupied park.

Forty hours after the Dalhousie tribe leave Zuccotti Park on Sunday morning, the New York police would sweep the tent city away.

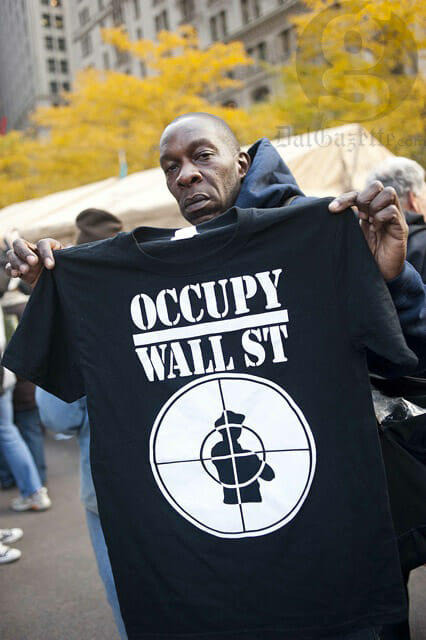

But that morning, the green peace flag was still flapping in the breeze, and the cops wandered their beats. Occupiers grumbled about the dirt, about the elitists, about the cops, about the t-shirt sellers, as they lined up for bagels and eggs. A bearded anarchist handed out fliers to passers by, and the morning shift of protesters held up signs demanding the end of capitalism.

On Broadway, a few red tourist buses passed by, and visitors craned out to snap pictures.

*All photos are by Angela Gzowski. Click here for more shots from the Gazette‘s coverage of OWS.