Mi’kmaq leader concerned acknowledgment of Orange Shirt Day is declining

The commemorative day honours thousands impacted by residential schools

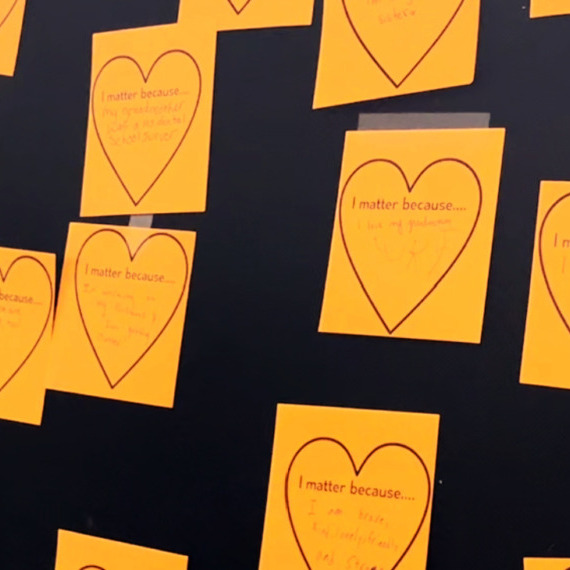

The Mi’kmaq Native Friendship Centre hosted an open house for Indigenous youth on Sept. 30 to mark Canada’s fifth National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, but one reconciliation project leader worries the day of commemoration is “dying.”

The federal government held the first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation in 2021 to honour thousands of First Nation, Métis and Inuit children who attended residential schools, those who never returned home and their affected communities.

Tammy Mudge is the co-director of strategy at Every One Every Day Kjipuktuk/Halifax, a reconciliation initiative at the Mi’kmaq Native Friendship Centre and a member of the Glooskap First Nation. She says that for the first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, lots of people participated, but that’s changed in recent years.

“There was just orange everywhere. Even in the streets, people were out and about,” she says. “[I’ve had] some conversations with folks around that, just seeing the decline of it — it’s dying.”

Until the late 1990s, the Canadian government forcibly separated at least 150,000 children from Indigenous communities, relocating them to residential schools. Children as young as seven endured abuse, starvation and disease as part of efforts to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture.

Hundreds of unmarked graves of children who died in residential schools were discovered in Canada in May 2021.

Andrea Paul, the regional chief for Nova Scotia in the Assembly of First Nations and a member of the Pictou First Nation, is a descendant of a residential school survivor. She says commemorative events are important for generations of families that were impacted by residential schools.

“For those of us descendants that may not have had the easiest childhood, being able to come to an event allows us to heal with others who may be experiencing the same things,” says Paul.

Several events took place in Halifax on Sept. 30, including exhibits at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic and the Nova Scotia Museum of Natural History. The exhibits highlighted the identity and culture of Mi’kmaq First Nations, aiming to amplify Indigenous voices and provide an opportunity for the community to reflect on the legacy of residential schools.

Mudge says the Halifax community must continue to honour the day.

“It needs to have new air breathed into it and focus again because it’s just going to be another report on a shelf that’s gathering dust like the other ones, and we don’t want that to happen.

“No matter what, as Canadians, everyone’s called to whatever capacity you have to move towards reconciliation. That was the commitment.”

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission released a report containing 94 Calls to Action, including the establishment of a national day of commemoration. The calls are policy recommendations designed to support the healing of Indigenous peoples. As of Oct. 1, Canada has implemented fourteen of the calls to action.

“Truth and Reconciliation is all about healing so we can stop the intergenerational trauma and our communities can be beautiful, safe, healing, connected places,” says Paul.

“Growing up, it wasn’t that way.”