As she checks off the “disabled” box on yet another job application, Stephanie Berry wonders what her honesty will cost her.

After four months of handing out what seems to be an endless stream of resumés and cover letters, Berry, 25, has yet to receive a call for an interview.

And with her Employment Insurance about to expire, her time is running out. She knows it’s a difficult time for anyone to get a job, she says, so she hesitates to point the finger to discrimination.

Berry has been visually impaired since she was a toddler. Now her degenerative condition has left her with only two per cent of her vision and three degrees of peripheral vision out of a possible 150.

Ironically, she studied employment equity practices throughout her master’s degree in education counseling psychology. But the reality of unfair hiring practices is hitting home as she once again hands out a batch of resumés.

“Some employers worry about hiring someone who has a severe visual impairment like myself. They worry about how their clients will react and how it will affect their business,” she says.

“I don’t think a lot of those employment equity policies are really being followed the way that they were meant to be followed. Companies just have one because it’s the politically correct thing to do.”

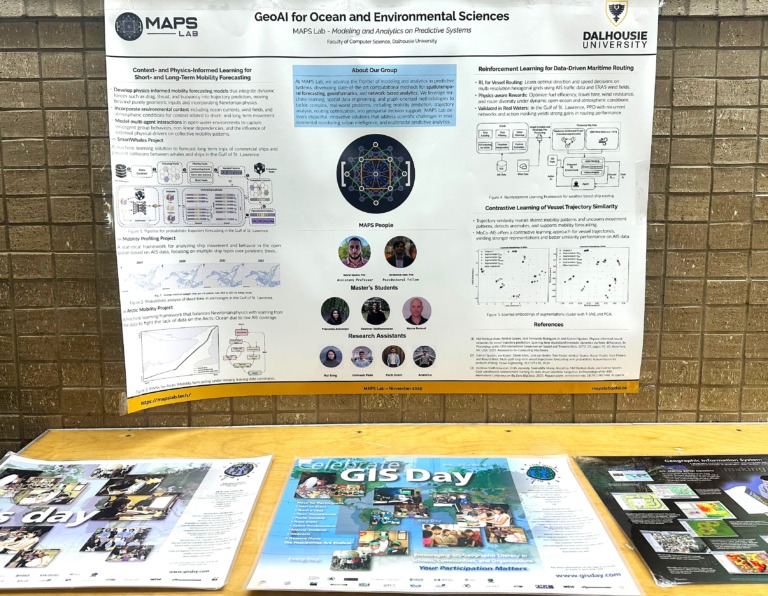

Since her graduation from the University of New Brunswick, Berry has applied to jobs at the provincial department of community services, the IWK, Capital Health, the non-profit sector, banks and endless businesses. She’s even applied to a few research assistant positions at Dalhousie, but with no luck.

At Dal she was fortunate enough to get an informational interview with the human resources department. She says the best advice she got there was to “continue to look at the website for job opportunities.”

She was told that while human resources was keen to accommodate for her disability once she was hired, it was really the departments themselves that would be doing the hiring.

Lindie Colp-Rutley is the equity analyst at the Office of Human Rights, Equity and Harassment Prevention at Dal. She makes sure the university is in full compliance with the federal Employment Equity Act, in order to receive federal grants.

However, she says that several groups, such as visible minorities, aboriginal and disabled persons are still underrepresented at Dal. Her statistics come from a census that requires staff and faculty to self-identify.

“We have lots of activities from recruitment through to promotion in the workplace to not only encourage hiring of those groups so we are more representative of the workforce, but to have them fully participate at Dalhousie,” says Colp-Rutley.

Berry says she is actually a speedy typist and can use a computer better than most. Through a screen reader program called JAWS, her computer will read out to her whatever is on the webpage. JAWS can be adapted to most computer programs, but the employer must take the initiative to look for compatibility.

Websites pose a challenge to the program, though. They can be fully or partially accessible, or not at all.

Berry, who faces this frustration every day, says she would love to see laws in place that require websites to be accessible in the same way that public buildings are required to be accessible.

For now though, she is still looking for jobs in Halifax.

“If I can qualify for social assistance, then I might go on that for a month or two while I keep frantically applying for jobs,” she says. But she has already begun to apply for jobs outside of the city.

“I really want to make Halifax my home, though.”