Created in Uzoma’s image

Dal student shares his experiences with anti-Black racism

Editor’s note and trigger warning: The following article contains detailed discussion of anti-Black racism, racist slurs and attempted suicide.

On June 5, I spoke at a candlelight vigil to commemorate Breonna Taylor, Regis Korchinski-Paquet, George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and other recent victims of police brutality.

Being included and speaking my truth to my Black brothers and sisters was a great privilege, and one so many do not get. That opportunity inspired me to write this letter, to expand on my thoughts, experiences and hopes for the future.

The recent murders of Black individuals in the United States have once again thrust racial tension and racialized violence into the public eye. People are stepping up to denounce racism, police brutality and racially motivated hate crimes, to an extent I have never seen before.

As a Black man of mixed parentage, who grew up as one of the few Black people in a province filled with deep underlying racial hatred, it has been an upsetting few weeks. The constant discussion of race and the Black experience on the news, social media, at rallies and with both white and Black people has me reflecting on my own experiences of racism and how they affected me.

Early experiences with racism

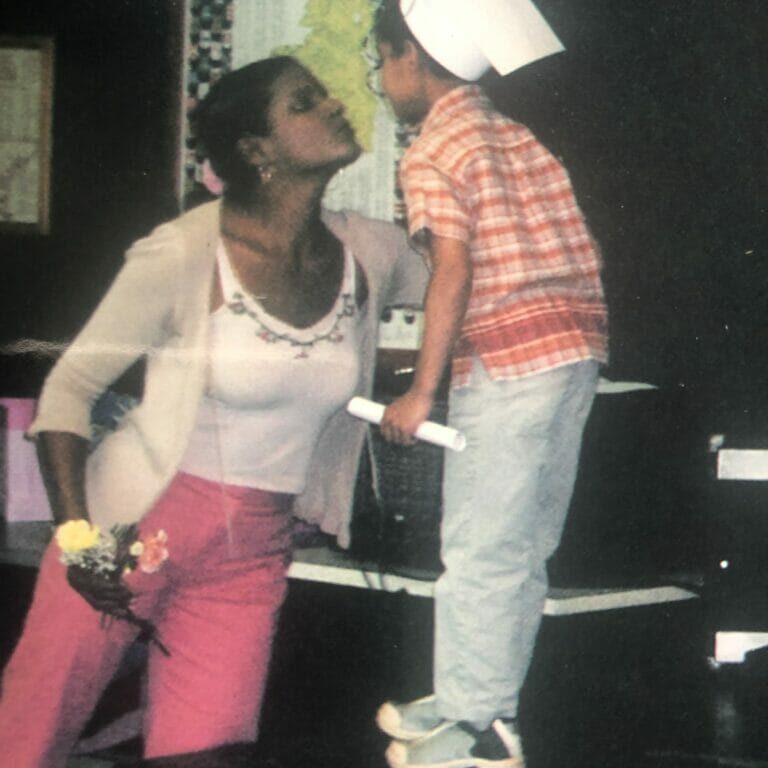

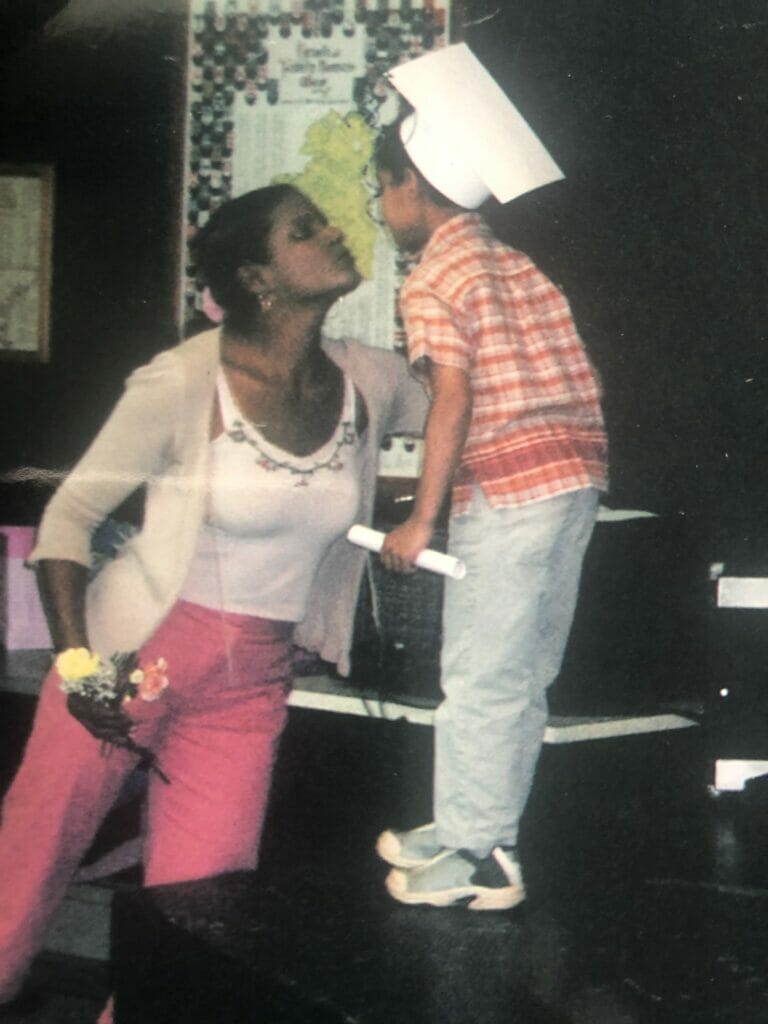

I was born to a Black mother and a white father. Like me, my inspirational mother Deborah and my two strong Black sisters Ellie and Amelia have faced discrimination since childhood. Before we even understood what it meant to be Black, in classrooms and on the playground, we were made painfully aware of what set us apart from the majority of our peers. My experiences go back further than I can remember.

One of my earliest experiences of racism happened when I was four or five, so young I can barely remember it, only this: I was told by a friend that my skin was the colour of “poo.” I went home to my mother and asked her why I was picked on. Unlike me, she has not forgotten that event.

This was not an isolated occurrence. Racism found my family again when we moved to Canada from England in 2004. At school in Prince Edward Island, children would single me out on the soccer field and at lunch for being Black.

I was in second grade when I was called a nigger for the first time. It was a word I did not understand: a word my parents had to explain to me, a word rooted in hate that defined much of my childhood, a word that causes me mental anguish to this day.

My family fought for justice for my sisters and I at school, but many of the teachers and administration at my elementary school did nothing. The boys who targeted me were lightly punished and the attacks continued for years. Teachers who dealt with my claims of racism said I was the one making trouble. They did not understand how the words and actions of my peers caused me and my family such pain.

My parents considered moving us to a different school in 2009 so my sisters and I could escape the violence of our classmates. My father attempted to meet with the commissioner of the school board but was shrugged off. At the same time, he and my mother wrote a letter to the school board describing the discrimination their children faced. Only then did the administration agree to a meeting and start addressing the racist bullying.

Years of battling the school administration and fights on the playground took a toll on us. I felt ignored, hated and subhuman. When my twin Ellie and I went to middle school, racism continued to follow us and greeted my younger sister Amelia as well.

In middle school, I was called a nigger more times than I care to remember. Despite the efforts of friends and the school principal, who fought for justice and challenged those who uttered those terrible words, more and more damage was done. On the school bus, I was called a monkey for the first time. Later on the same bus, I was threatened with a knife after being called a nigger.

I was in seventh grade when the murder of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin occurred. It will be with me always. He was only four years older than I was. For so many Black men and women of my generation, it was the first moment we became agonizingly aware of the extent of the hatred the white man has of us.

Shame and anguish

The culmination of so many years of fighting led me to hate my Black skin, my curly hair, my lips and my nose. Everything that makes me look different. In elementary school, I covered my arms with long sleeves in an attempt to conceal my differences. To this day, there are times when I hate my hair and try to hide it.

Anguish from years of abuse drove me to attempt suicide in 2012. That year was particularly bad. I tried to hang myself. The mobs of children who picked on me drove me to a point where I was so ashamed of my Blackness, I would rather die than be who my ancestors made me. I wonder, how many of my Black brothers and sisters have died that way? Not at the hands of the police, not lynched, but made to hate themselves so much they did not want to continue to live.

We are taught to hate our Black bodies, our hair and our Black features. We become ashamed to be Black. The shame I feel in my bones is a wound that may never go away. As a teen, it led to social anxiety. Today, stares from anyone and eye contact with white people make me uncomfortable.

Every time someone grips their purse as they walk past me, follows me in a store or makes comments about my colour, I feel this shame. It is a feeling that plagues many of my brothers and sisters. It is something I would give so much to unlearn. I buried my feelings and distanced myself from my Blackness as much as possible to avoid the pain.

Shame makes me terrified to meet a friend’s family, a girlfriend’s parents or to talk about my experiences. The same shame makes me terrified to think of how my peers will react to the thoughts and experiences I am now openly sharing.

This shame drove me to resent my mother for making me what I am. I wanted so desperately to be white, to look like my father. If I did, other kids would never say to me, “At least my dad looks like me.” That I once resented my mother for making me Black still makes her cry, and for that I will never forgive myself.

Within the Black community, this shame and hatred can present itself in the form of colourism. Our darker brothers and sisters often wish to be lighter to be considered more beautiful. They long for looser curls and mahogany skin, which is fetishized and considered exotic. Like me, our lighter brothers and sisters wish to be darker so they can feel they truly belong amongst their Black peers. We wish for curlier hair and ebony skin. How ironic it is that I can simultaneously wish to be both lighter and darker.

Colourism divides families. Parents sometimes favour their lightest children. It causes pain to all. Many of us feel we will never be enough. As a community, we must unlearn this way of thinking. Black is beautiful in all its forms.

Anti-Black racism still exists

I’ve heard people argue that systemic racism no longer exists, or if it does, things are much better than they once were. If our systems were not inherently racist, why do I have to be twice as polite, twice as friendly and twice as calm with others to get the same treatment white people enjoy? Why does my father, a man who served as a police officer in England for 20 years, end all our phone calls with the advice, “Be careful of the police”?

In Halifax, we are harassed, targeted by street checks or like Santina Rao, beaten in front of our children in a department store. My mother is regularly harassed at stores, questioned and humiliated by racist employees. How many more of our mothers must endure this treatment? Why are we followed by staff and watched carefully by clerks?

I have been intimidated by the police here in Halifax and targeted unlike my white friends. One fall evening, a friend and I were walking to a party. Police officers shut the party down and decided to question us before we had even entered the premises. My white friend was talking at the same time as the officer. I told him to be quiet so the officer could speak.

Without warning, the officer turned and stepped toward me. Aggressively and mere inches from my face, he asked what I had said about him. Why did the officer take such issue with me and not my friend who was speaking over him? What gave him the right to tower over me and yell in my face? We are so conditioned to fear the police by what we see on the news. That fear is what makes me record every interaction I can with the police.

I was pulled over once for a burnt-out tail light. The fear of the police officer made me shake and hyperventilate. It was a fear I didn’t even realise I had prior to that event. If systemic racism is not still alive, why do my non-white friends literally cry on my shoulder, terrified my life will be the next one stolen by police officers who have sworn to protect and serve us? The pain we feel is excruciating. We are fed up. Enough is enough.

To a better future

It’s fashionable now to share petitions and black squares to show support for Black people. The same white people who mocked my features, denied my Black identity due to my upbringing and mixed parentage and called me a nigger are sharing these posts. I hope they have changed and become allies.

What white people reading this must understand: We are not your educators. We are hurting. We are exhausted and some of us ashamed. Our opinions are just as diverse as yours. There is no Black hive mind. We are individuals with our own thoughts, feelings and experiences. What many of us want now is love and support. However, I can assure you we will struggle and fight this war alone if we must. We are strong and resilient. We will not tolerate virtue signalling liars who use us as pawns for their own agendas or for social clout. If you want to be a true ally, check on your Black friends, stand with us and teach your children racism is wrong and to love unconditionally.

To my Black family: my cousins and aunties along with our brothers and sisters worldwide, I have felt pain like yours. We are hurt, but we are strong. Although we are separated by distance, we stand together. We will follow in the footsteps of our mothers and fathers, grandmothers and grandfathers. We stand on the shoulders of Malcolm X and Dr. King. We will emerge victorious and one day create a world where our Black children are accepted and judged by who they are as humans.

I thank those who have inspired me and fought for me. Those who love me for who I am regardless of my melanin. To my “brother” Patrick, to Samantha, Dexter, Norman, Charlotte and other non-Black people who have taken up my fight and stood with me: you have given me a shoulder to cry on and picked me up from my lowest points. For this, I am grateful.

Most importantly thank you to my Black friends and my family: I could not do this without you. To Binta, John and all my other Black peers, I will always stand with you regardless of any circumstance. To my father Robin, thank you for fighting for us as hard as was humanly possible at the worst of times. To my darling, unapologetically Black mother Deborah, and my beautiful, amazing and intelligent sisters Ellie and Amelia, thank you for inspiring me every day.

My mother’s name at birth was Uzoma. In Igbo, a language originating from Nigeria, it translates to “the good path.” It is tattooed on my arm as a constant reminder of her love and support, and everything I owe to her.

Only together can we create a world rid of hate and prejudice where our children can dwell together in peaceful union. A world where we follow the good path.