The proof of white privilege in Passing

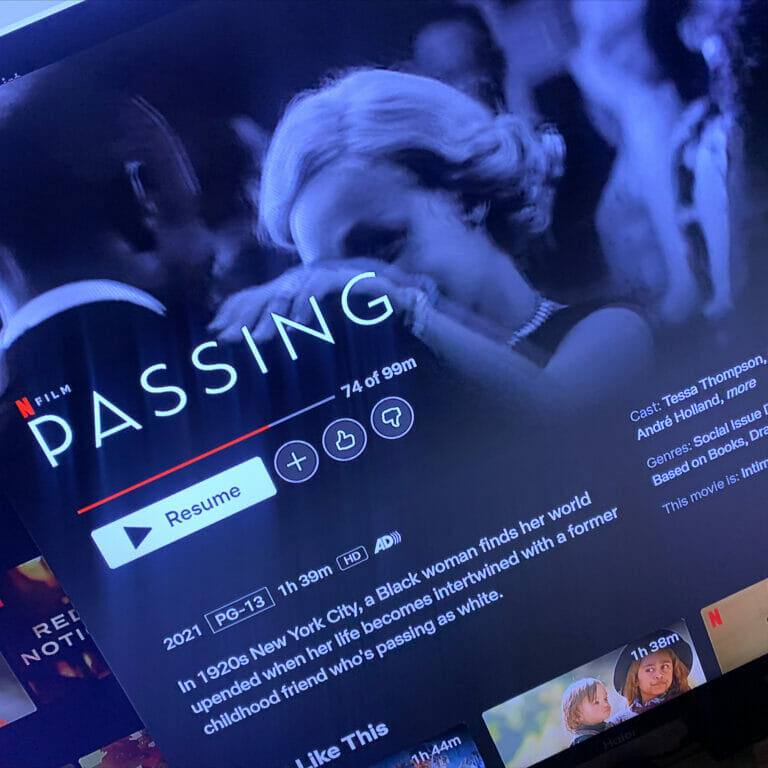

Why Rebecca Hall’s new film is essential viewing

Editor’s note and trigger warning: The film described in this article contains racism, including racial slurs and descriptions of racial violence.

Rebecca Hall’s Passing offers a unique glimpse at life in the 1920s and a prime example of white privilege at work.

Passing is a black and white movie based on a novel of the same name. The film takes place in New York City and focuses on two childhood friends reuniting after years apart. While both women are Black, one “passes” as white and lives as such with her white husband and young daughter. The other woman lives as herself with a Black husband and their two children.

Passing is poignant, thought-provoking and devastating. It made me terribly uncomfortable, and I feel that’s exactly the way it should make me feel. It offered a perfect example of white privilege and a terrible look at how widely accepted racism was only 100 years ago.

There are many themes within this film, including the premise of changing oneself to fit the mass concept of “normal,” women changing themselves for the acceptance of men, and the heartbreaking prevalence of white privilege. Passing is a film everyone should see at least once.

The good and the bad

While Passing has some important messages, it’s a little slow getting them across. If you do take my advice and watch this film, be prepared for a slow, leisurely pace.

The climax and resolution of the film all take place in the final 20 minutes. Without leaving any spoilers, I’ll say it ended just as I expected in some ways, and completely unexpectedly in others. The only thing that fans can be sure of from the beginning is that Clare’s lies are bound to catch up with her eventually.

What Passing lacks in energy, it more than makes up for in acting. Tessa Thompson as Irene steals the show, while Ruth Negga’s depiction of Clare keeps you on your toes. The chemistry between these actresses at times sizzles with electricity you just can’t fake.

With a few loose ties left dangling in the wind by the finale, Passing doesn’t feel like a film with a defined ending. It leaves us to interpret some of the events these women experience, and that interpretation forces you to think about the world they live in.

White privilege didn’t die out with prohibition

Watching Clare struggle with her identity, it’s easy to see white privilege at work in Harlem. From the opening scene, with two ladies discussing how awful it is to let white children play with Black dolls, to Clare’s husband John spewing racial slurs about his own wife’s hidden race, Passing chips away at the rose coloured glasses of denial and forces white viewers to take a good look at our reality.

We may not see the same public displays of racism as they did in the 1920s, but that doesn’t mean racism doesn’t exist. And that racism puts a heavy load on the scales of equality. This is where white privilege comes in, tipping the scales further.

White privilege is a subject that has seen much debate over the last few years with the rise in popularity of the Black Lives Matter movement. It seems hard for some white people to accept the concept, especially if they feel they have lived less than fortunate lives.

Passing helps put this in perspective. It shows us that white privilege isn’t growing up rich or having everything you want. It’s blending into a society that has deemed us the “norm.” Letting our kids go out and not worrying they won’t come home because somebody mistakes them for a criminal. It’s applying for a job and knowing the colour of our skin has no impact on the decision. It’s flying on a plane and knowing nobody will flag us as a potential risk because of our religious garments. It’s driving home and knowing we won’t get pulled over because the police officer didn’t like our skin tone. It’s injustice.

With Black History Month soon at an end, we should all turn our thoughts to supporting Black communities across Nova Scotia. Sometimes the best way to do this is by recognizing the faults in ourselves and working to be better. We can’t change the colour of our skin, but we can work to change the way colour is used to further ignorance and inequality.

If Clare’s devastating story teaches us anything, it’s that white privilege is a very serious problem. And it’s important to remember, it hasn’t gone anywhere.