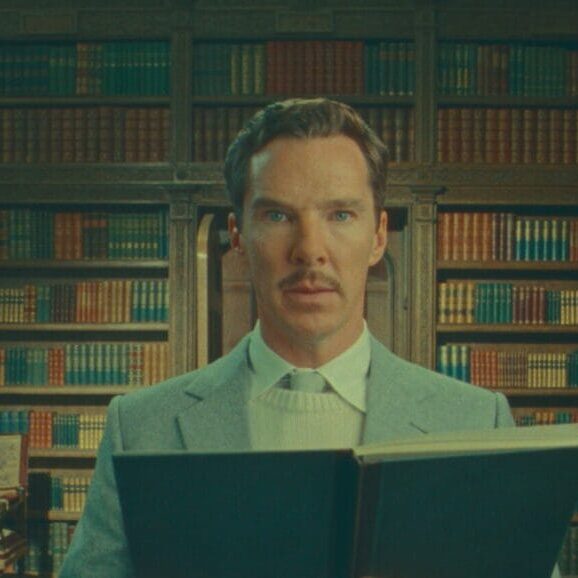

A wonderful story: Wes Anderson adapts Roald Dahl

The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar gets the big screen treatment

Filmmaker Wes Anderson created four short films for Netflix adapting four of Roald Dahl’s stories. One of the stories he adapted is Dahl’s The Wonderful Story Of Henry Sugar, released by Dahl originally in a collection titled The Wonderful Story Of Henry Sugar and Six More.

This collection features a variety of stories that include memoirs from Dahl’s own life. I remember reading this collection when I was younger and not being entirely sure that all the stories weren’t non-fiction.

The Swan (also released as a short film by Wes Anderson), The Hitch-Hiker and The Mildenhall Treasure, all stories from the collection, could also be believable as true stories. They are all told in an authoritative third-person voice. Dahl is playing with his readers here and relies on them not having developed a proper sense of skepticism.

A similar technique was employed by Victorian gothic authors. One of the hallmarks of a gothic work is that it’s told as a true story; The Mysteries of Udulpho and Lady Aubrey’s Secret utilize this trope. Other writers presented stories as taking place while they’re read with readers having to piece them together from a variety of perspectives, as in Bram Stocker’s Dracula.

The edge to Dracula came from it taking place in a world that resembled our own, insinuating that humans were capable of the terrible acts portrayed. In contrast, Dahl’s stories focus more on the peculiarities that could take place within our world in a more lighthearted manner.

Can you remember that feeling, observing something peculiar that you couldn’t quite explain? That time in your life when you had to look up at everything and every once in a while something would happen that you couldn’t explain and grown-ups didn’t seem to notice?

I was always too scared to ask adults for explanations to questions that I figured would be seen as silly and childish. Henry Sugar plays right into that. Everything seems relatively modern and explainable, yet there’s an obvious incongruence to our reality.

Reliance on Orientalism

It’s also necessary to point out that Dahl and Anderson both heavily rely on elements of Orientalism to give their stories life. Henry Sugar relies on a narrative of vaguely Hindu ideas of monks and spiritual enlightenment that work because the film is written for a Western audience.

I had hoped that Anderson would have improved on his tendency to use orientalist tropes after The Darjeeling Limited, but the India he portrays in his films remains a vaguely foreign place that happens to speak English.

The supernatural abilities that Henry Sugar develops are explained as the meditations of a mysterious yogi who lives in the jungle, eerily similar to Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book. Kipling and Dahl are dead and buried, but I feel it important to highlight how Indians that appear in Anderson’s films are either very British or entirely offensively “primitive.”

Story structure

Henry Sugar’s story is a Russian nesting doll of other stories as it’s revealed to be a story within a story within a story. The reader is immersed within the layers of storytelling and Dahl blurs the line between feasible reality and fiction.

Interestingly enough, one of the reviews that are highlighted on the back cover of the book calls Dahl “that great magician.” The reader knows in the back of their head this is a fictitious story. In a fashion reminiscent of Yann Martel’s Life Of Pi. Martel and Dahl’s stories urge the reader to decide if they favour a logical or fantastical understanding of the events depicted.

Anderson beautifully translates this to the screen through a series of tableaus and monologues. The story is always being told, there is constantly a narrator on screen. Think of The Grand Budapest Hotel, The Royal Tenenbaums or The French Dispatch.

Every scene appears to be handcrafted to Anderson’s exact specifications. Anderson ensures the viewer can never suspend their disbelief and must remind them the story is being told to them. Nonetheless, the audience will still be immersed in the world of both Dahl and Anderson’s The Wonderful Story Of Henry Sugar. Both of these artists are intrinsic to their plots because everything is interpreted through them.

This might not be 1984, Crime And Punishment, Citizen Kane or The Godfather, but, The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar and Six More earns the title of classic literature in my book. “Classic literature” doesn’t always need to be long complex narratives, sometimes it’s the short, sweet and whimsical tales that are considered classics to individuals.

Who determines what a classic is anyway? I, for one, am extraordinarily grateful that Dahl and later Anderson privileged us with this story that fits my criteria for a classic.