FIN: AIFF roundup

A closer look at a few of many films presented at the recent FIN Atlantic Film Festival

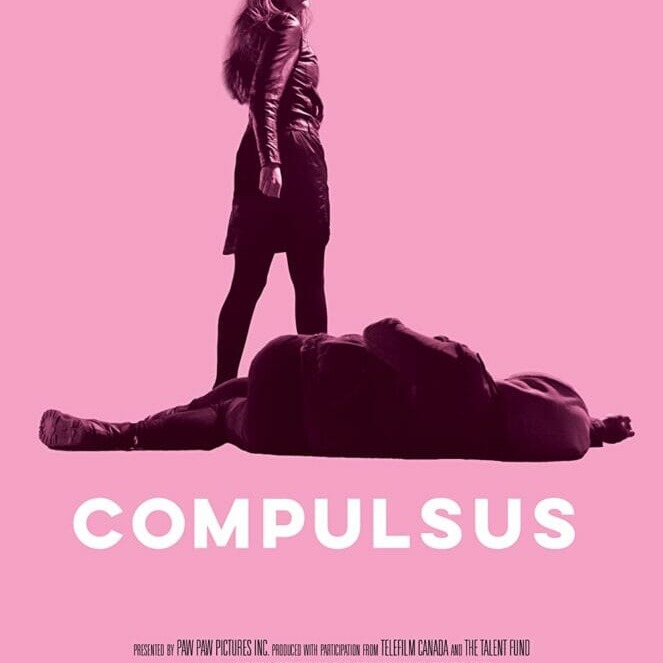

Huesera (2022), Michelle Garza Cervera

By Natalia Tola

Country: Peru, Mexico

In Latin American culture, mothers are both kind healers and ruthless matriarchs. They sweep living rooms, wipe babies’ tears and control any family matter with one movement of their hand.

And so, watching the physical, gory undoing of the mother in Huesera is an uneasy yet liberating experience.

Huesera is a Mexican horror film following the story of Valeria, a soon-to-be mother whose so-called “blessed pregnancy” is violently disrupted by lurking presences and cracking bones. The audience is confronted with disjointed bodies, baby cribs set on fire and bloody legs dragging themselves through the floor.

As Valeria begins shrinking into a smaller, paranoid version of herself – she finds nothing but questioning from her partner and her family alike. Why can’t she sleep? Why is her paranoia causing her to lose weight? Will her previous failures prevent her from being a good mother?

She grows silent as the demons around her grow louder.

The power of Huesera lies in its sound mixing. The film directly aims to play with the sense of disgust: corpses falling onto the pavement, nails scratching walls, joints cracking time and time again. The sound is used to fit the environment and the jarring, realistic sounds keep the audience on edge.The film leaves a trail of breadcrumbs for the audience to follow, allowing a variety of interpretations. Some include: spiders as representatives of the terrifying power of femininity, criticism of rigid family structures and the experience women go through when feeling unheard during the discussion of their own bodies.

Close (2022), Lukas Dhont

By Natasha Fortin

Country: Belgium, Netherlands, France

Close is a 2022 Belgian film directed by Lukas Dhont. Shot primarily in French with some Dutch and Flemish dialogue, the film explores the friendship of thirteen-year-olds, Léo (played by Eden Dambrine) and Rémi (played by Gustav De Waele).

The boys spend their summer days together, inseparable, but when the new school year begins their intimate friendship becomes strained. Léo finds himself in the company of new friends, pushing Rémi away. When Rémi disappears Léo struggles to understand what happened and grows closer to Rémi’s mother in hopes of finding clarity.

Close illuminates the pain and suffering one feels at the end of a friendship. There are references to societal divides and the homophobia that is still prevalent in society. Themes of mental health and guilt are explored as they are the result of stigma that affects Léo and Rémi.

The breathtaking cinematography allowed for dialogue and purpose when no words were spoken. This dialogue in silence allows for a repertoire of expressions. The silences embodied the secret love the boys cannot verbally articulate and when there was dialogue, it was lyrically captivating. The lighting and colour choices masterfully portrayed the emotions experienced by the characters. As the characters moved throughout their lives, every action appeared natural and effortless.

The unravelling of a heart-wrenching series of events led to the audience having tightened throats and short breaths. By the end credits of the film, there was a soft wave of sniffles circling about the cinema as the reality of the story was laid out so meticulously before our eyes.

Close won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival (2022) as well as the Sydney Film Prize at the Sydney Film Festival (2022). Close was selected as Belgium’s entry for the international feature film category at the 95th Academy Awards which will be held on March 12, 2023.

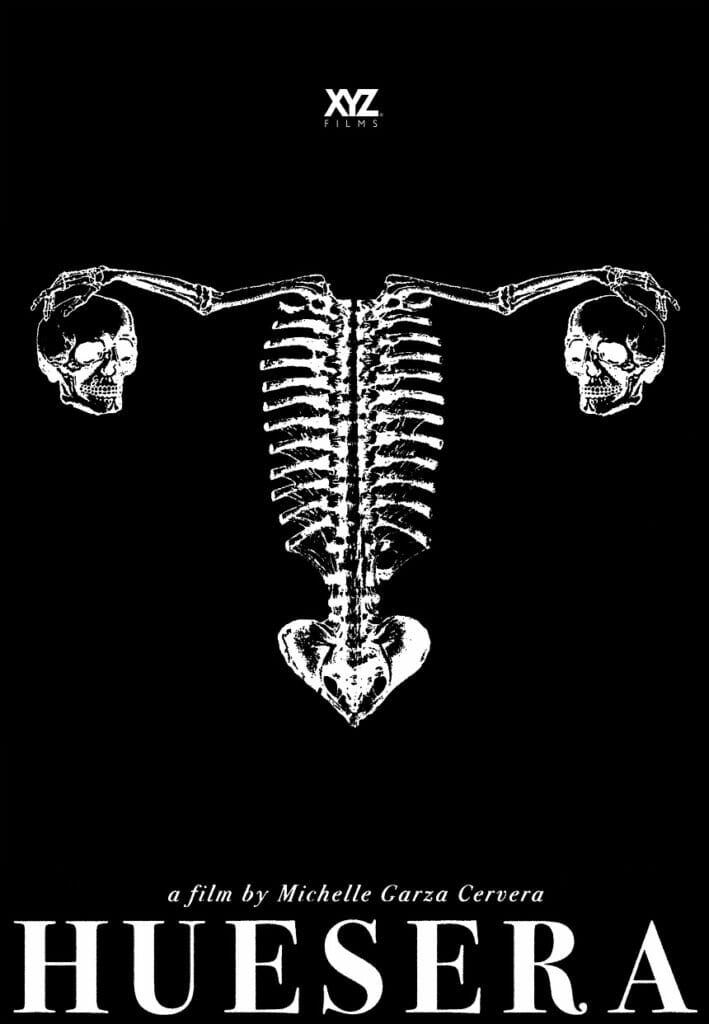

Piggy (2022), directed by Carlota Martinez-Pereda

By Olivia Piercey

Country: Spain

Piggy is an intense thriller following the story of Sara, a high school girl who is body-shamed by her peers and former friend Claudia, who is trying to fit in with the popular crowd. “Piggy” is a cruel nickname Sara’s bullies came up with. Her parents own a butchery.

One afternoon after her bullies nearly drown her, take her clothes and phone, then leave her nearly naked to walk home, Sara notices a strange man. On her way home, a van stops in front of her.

Sara witnesses a bloodied hand hit the back window of the van. As her bullies are held hostage in the back of the van, the kidnapper drops Sara a towel and drives away. The film follows Sara’s choices after witnessing this and the development of her feelings towards the kidnapper.

Martinez-Pereda takes an imaginative look at how insecurity, fear and anger can lead to destructive decisions and disastrous consequences. The use of sound in the film sets an uncomfortable eerie tone that builds the viewer’s anticipation. The film uses repetitive sounds — a knife hitting a cutting board, or footsteps approaching — and increases the tempo, signifying something is coming. Silence is interrupted by slamming doors or a thud on the window. You never know what will happen next.

Piggy will leave you feeling uneasy and questioning your morals. This film is great for anyone who is entertained by spine-chilling stories.

You Can Live Forever (2022), directed by Sarah Watts and Mark Slutsky

By Olivia Piercey

Country: Canada

After the death of her father, Jamie, portrayed by Anwen O’Driscoll, is sent to live with her Jehovah’s Witness aunt and uncle while her mother processes the loss.

She becomes close with one of the devout Witness girls, Marike, played by Jennifer Laporte. While Jamie learns more about life as a Jehovah’s Witness, she and Marike develop strong feelings for each other. The film follows the story of their bond, and how the two girls navigate their feelings forced into secrecy.

Co-directors and writers Sarah Watts and Mark Slutsky show a story of growth, faith, love and heartbreak. Set in the ’90s, You Can Live Forever gives an incredibly intimate portrayal of queer relationships within religious communities. Watts and Slutky’s use of distance and spacing between the characters creates an electric tension making the smallest moments feel the most important: sharing a book, looking across the dinner table, or slightly touching hands.

Jamie and Marike meet at a Witness meeting and religion is woven into their relationship, as if it is the third person. Jamie, wanting to spend more time with Marike, goes on field service and attends Bible studies.

The use of montages and time jumps build the relationship and their bond quickly. As an audience member, you too become swept away into the whirlwind romance with Jamie and Marike. Watts and Slutsky include windows and cracked doors in the shots of intimate moments. These details allude to Marike and Jamie’s fear of being seen together, and make the audience hold their breath, waiting for the inevitable.

This incredible coming-of-age story shows how some bonds change and challenge you while leaving lasting impacts for the rest of your life.

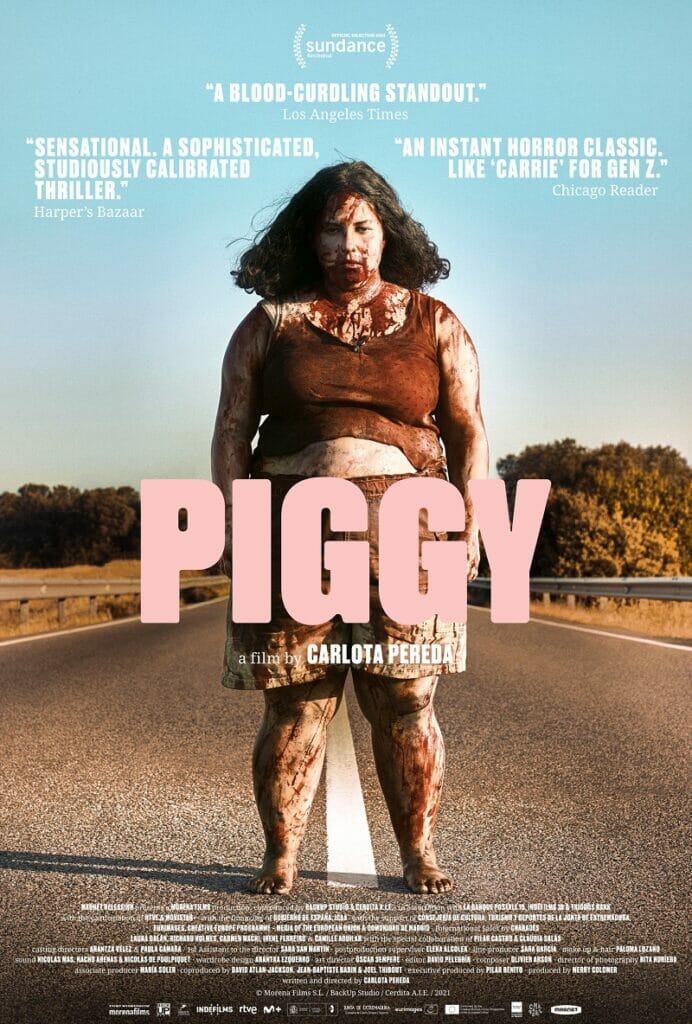

Compulsus (2022), Tara Thorne

By Gökçe On

Country: Canada

Compulsus follows Wally (Lesley Smith), as she goes through the city at night, haunting “bad men.” Thorne’s debut takes its audience through dark streets with a vengeful agenda against misogyny entangled with a queer love story.

With striking lighting, cinematography and sound, this story is fleshed out by technical elements. The choice of primary colours in lighting during scenes where Wally is engaging with her friends, or her love interest, is in stark contrast to the scenes where she is stalking and striking men.

The spoken word poetry written by Halifax’s poet laureate, Sue Goyette, being incorporated in the breaking moments of the film, felt like a sign for the audience to take in Goyette’s work while digesting the events up until that moment. Smith’s delivery of the poems as Wally added to her on-screen performance, seemingly giving her a chance to dig deeper into her character’s subconscious.

Compulsus is a film you want to love. It has momentum, emotion and confrontation. However, it falls flat. It’s upsetting that the film doesn’t delve deeper into why women are scared and how this fear affects anyone else other than Wally – an upper middle-class white cisgender woman in her 30s.

As much as the audience wants to believe in this world, where a woman can go out in the middle of the night and physically harm men without getting caught or getting harmed, it’s delusional. The limited perspective hurts when reality strikes you rather harshly in the slower moments of the movie and headlines of numerous femicides start running through your mind. Not to mention, what’s in front of your eyes can only be considered realistic within Canada, at best. Without intersectionality and privilege considerations, conversations about patriarchy lack depth. Films like Compulsus will never feel complete.