Going nowhere and back

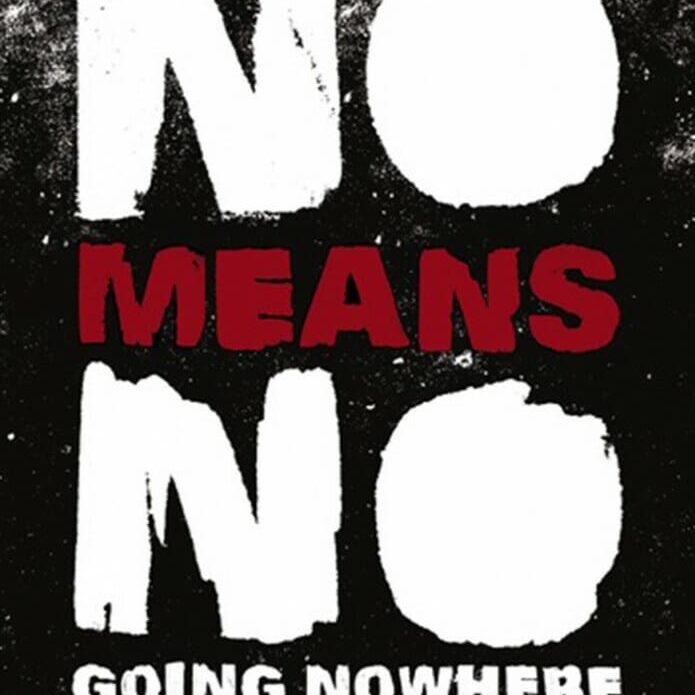

In 2012, Mark Black’s first book NoMeansNo: Going Nowhere was released as a part of Invisible Publishing’s Bibliophonic music series

In 2012, Mark Black’s first book NoMeansNo: Going Nowhere was released as a part of Invisible Publishing’s Bibliophonic music series. The non-fiction book is part chronicle of genre-defining B.C punk band NoMeansNo, and part fan memoir of Black’s and his brother’s teenage punk years in Cape Breton. Black is currently a student in Dalhousie’s Master of Library and Information Studies (MLIS) program. The Gazette spoke with Black about his experiences writing the book, Nova Scotia punk culture, and his upcoming projects.

“They were basically nerds who played weird, misanthropic punk rock,” Black said of NoMeansNo, formed in 1979 by brothers Rob and John Wright.

“They’re a band I admired and liked, and I always saw that there was not a complete narrative about them. I don’t attempt to tell that in the book, like ‘the history of band.’ I could kind of see parallels in the fact that they’re from Victoria, and that’s an island and that I grew up on Cape Breton Island, in that [NoMeansNo are] brothers, and in my own relationship with my brother.”

In *Going Nowhere,* Black writes about discovering NoMeansNo through his older brother, who moved to Nelson, B.C. from economically depressed Cape Breton in 1998.

“He was just into anything that was really extreme,” Black says of his brother’s teenage musical taste.

“A lot of thrash metal, this band called DRI…anything that was sort of offensive that you could acquire in Cape Breton, he would have. So, my brother would have all of these mixtapes laying around and I would steal them. At one point half of my record collection belonged to him. It’s stuff that I inherited from him after he moved away.”

Black doesn’t see punk as the thriving cultural movement it once was, but the ethos that inspired him as a teenager still informs his life.

“I look at it as just a filter, how I look at things,” Black says.

“With school or work, when I think about libraries, I think about libraries as probably the most punk place to work, because it levels the playing field. Everyone’s opinion matters, access to information matters, everyone’s input matters. I think that’s probably the best way to look at punk.”

Black is currently working on a history of Maritime punk that will likely be, in true punk spirit, a short run self-release, “like a limited press LP.” Punk and D.I.Y cultures had (and for some, still have) a rich following in the Maritimes due to geographic isolation and post-industrial economic downturn, Black notes.

“The Maritimes are kind of a dreary place, and there’s nothing for you to do. There’s nothing, right? If any place is the antithesis of Reaganomics or preppy culture from the 80s, it’s the Maritimes. In small towns with rednecks, either you’re a redneck, or you push against that. People had to put on their own shows… You have kids doing shows in the edge of the world and mimicking things that they see coming out of L.A or wherever in interesting ways…Halifax seemed like New York to me… Café Ole (a long-running all-ages club popular in the 90s) was kind of a mythical place.”

Black sees punk as an outlet for the social problems and dead-end economic situations facing the kids he grew up with on his home island of Cape Breton.

“You’ve got to have something to push back against. With C.B, you’re dealing with kids who are isolated. They know that they’re not going to get a job when they grow up. They’ve seen their parents get laid off and frustrated. You’re almost written off, in a lot of ways. You’re a teenager full of angst and you want to listen to something loud that says something to you.”