Q&A: novelist Hannah Brown

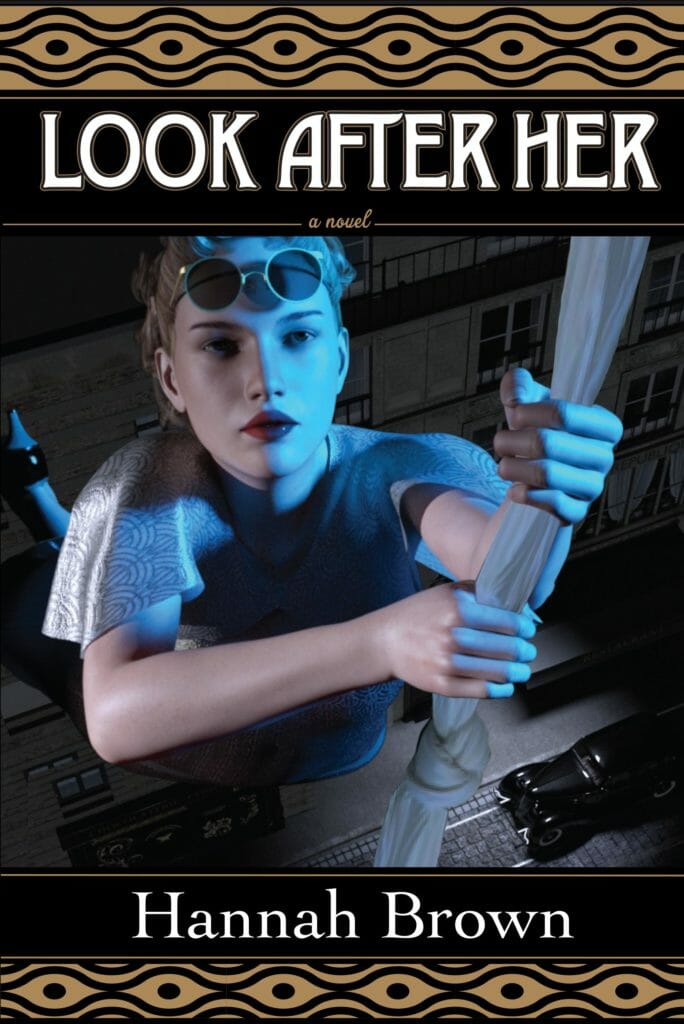

The acclaimed writer talks about her debut novel Look After Her

A conversation with novelist and screenwriter Hannah Brown is a remarkable experience. The Toronto-based author’s eloquence and wit reflect her vast expanse of knowledge of the literary world. Her thoughts are as fascinating as the characters she has created in her debut novel Look After Her, published in September 2019.

Look After Her follows Jewish sisters Hedy and Susannah who live in late 1930s Vienna. After a family friend kidnaps them, the sisters are forced to work in a brothel. A story of heartbreak, courage and trauma ensues.

The Dalhousie Gazette sat down to speak to Brown about the themes of feminism, responsibility and art in her novel.

The Dalhousie Gazette: Your novel is about two sisters, Hedy and Susannah. How would you characterize their relationship?

Hannah Brown: Susannah is anti-social. She blurts out things that she shouldn’t. She enjoys causing consternation. She swears freely. Hedy is the older sister, more conventional, more inclined to be agreeable to her elders. The title of the book, Look After Her, is the question: ‘Who is doing the looking after?’

I was close to my late first cousin. We would do things, and I could not tell you whose idea it was to do those things. It felt like we had a shared mind, from infancy. She was born three months after me.

My mother had one sister, and they were very close. My mother said, ‘I fought with her every day of my life, and there was with no one to whom I was closer.’ There’s an intimacy and closeness in sisters.

What did you want your novel to say, then, about our responsibility towards the people we care about?

I hope my novel suggests that we need to be generous with other people, partly because we cannot know all their secrets. No matter how close you are to someone. We have to accept that the other person has their own life, that we can’t know everything and that we can love them even if we don’t know everything.

We can’t discuss the relationships between women without mentioning feminism. Would you describe your novel as feminist?

I can’t imagine talking about relationships between women without talking about feminism! My book is published by a feminist press that’s been around for 40 years. And I’m so happy that it rides on that wave of understanding.

I think because [Susannah and Hedy] have profoundly different experiences with sexuality, I think there is maybe more than one aspect of sexuality [that] is presented. I would say that these are relatively naïve people when they begin. They have lived relatively isolated lives … and yet, they have impeccable manners because of the class they belong to.

When you’re with your sister, you can basically say anything. So, there is frank discussion of sexuality, but I wanted to use the feminism that I understand and live. I wanted to use it with a light hand. I wanted the story to move. That’s part of my screenwriting craft. There’s a lot of frankness [in the story]. There are also other layers that are there for you, if you know how to read them.

Hedy and Susannah’s parents are art lovers, and the sisters eventually encounter famed artist, Egon Schiele. What role does art play in the story?

Well, Hedy is an aesthete. At one point, [the owner of the brothel where Hedy and Susannah work] asks Hedy to fix a hat, and Hedy hates this woman. She can’t stand her. But she can’t not make that hat look better because for Hedy, doing justice is doing justice, and that means making that hat looks as good as it can.

Whatever definition of justice you choose, it has to be universal. So, if your focus is a social sense of justice, then you will be respectful to the person on the street holding out their cup. You can’t [ignore] the person asking for change. So, for Hedy, she cannot make a person she hates look ugly. It is against her sense of aesthetic justice.

How, then, does Hedy’s justice differ from Susannah’s?

[Susannah’s] sense of justice is narrow. For her, justice would be to escape and to be allowed to have her own life … and if the opportunity arises, she will take that chance. I don’t know how I would categorize that sense of justice. But Hedy’s, I think it’s ancient and retributive. It’s like a hammer on coal. It has to do with respect for the other person.

What do you hope your readers will take away from reading Look After Her?

I hope they are amazed, in a way, by the consideration of other perspectives than perhaps what is conventional.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for length, clarity and style.