ScanDALous sixties

How rock n’ roll, JFK, and finally building a Student Union Building shaped an eventful decade for Dal

A bitter feud articulated in the Dalhousie Gazette opinion’s section erupted between the classy-music and swing dancing Dalhousie University students, versus the rock n’ roll listening boot stompers.

It was January 13, 1960: Dalhousie wasn’t immune to the cultural changes of the times.

The Gazette editorial team was criticized for being too critical of Dal as an institution and of the government at the time. The Editor-in-Chief, Peter Outhit, and his team responded by writing that “politics is not a sacred cow,” and the Gazette’s fierce critique of the powers that be wouldn’t be ending anytime soon.

In a bullet-form article published in Volume 92, Issue 10, the Gazette team wrote they hoped the sixties would bring:

- Fewer feminine knee socks, flat shoes, and shapeless sweaters.

- A better-conditioned football team and an enlarged stadium to better accommodate overflow crowds.

- A few enthusiastic student leaders who aren’t afraid to criticize present student activities, and then get out and do something about them!

In February of the same year, the Gazette published it’s Now or Never issue dedicated to the fact that students had been fundraising for a Student Union Building since 1957 and had yet received one.

The creation of a SUB would come down to a referendum vote on Feb. 18 and 19.

Students argued via the Gazette’s opinion that the SUB would bring a better snack selection, a student bookstore, and a barbershop. The inclusion of a billiards room was also important – and rooms used for interfaith organizations.

The lack of a communal space for “both sexes” to join together was a troubling issue for Dal students.

Potential Soviet spies – or just innocent Russian students – were also a troublesome issue for students as a group of four Russian students visited Dalhousie on November 1, 1960.

The Gazette covered a panel the four students gave on campus, on how Russia prepares students differently in order to serve a communist society.

“They said although ‘adequate’ preparation was being given to students in the humanities, engineers and specialists were being prepared for many branches of economic development,” the Nov. 10 issue reported. “They said Russian students also had a great obligation to the Soviet government.”

According to the Gazette’s coverage, while some students were skeptical of the visit, the Russian students stated they hoped their visit would strengthen ties and understanding between the USSR and Canada.

The political debate at Dalhousie in the sixties was only starting with discussions of unions and Russians.

The Gazette covered the “Dief the Chief” visit in 1961, which must have been poorly received by students, as the Gazette editorial team decided to publish a gimmick where they quoted then-Prime Minister John Diefenbaker as saying nothing in his entire speech.

From Dalhousie Gazette Archives: Volume 94, Issue 8.

“Having agreed that a report is necessary, the Gazette would rejoice if any member of the Prime Minister’s audience would approach us and inform us just what we should report. Although there were several Gazette reporters and editors present, almost all came away empty-handed, devoid of any sort of notes from which one might mould a news report,” wrote then Editor-in-Chief Mike Kirby in his editorial.

“How, indeed, is one to report a speech in which nothing was said?”

“Although Dalhousie was proud to welcome Canada’s Prime Minister, we regret the fact that Mr. Diefenbaker insisted on addressing the students present at a nursery level.”

In a cutting line, Kirby, wrote “It is a small wonder students revolt at being told continually that they are the nation’s future leaders, if the nation’s present leaders treat student with such marked intellectual disdain.”

While Diefenbaker didn’t make the politically-minded students of Dalhousie swoon, a man by the name of Thomas “Tommy” Douglas did. Douglas was ex-Premier of Saskatchewan at this time, and national leader of the federal New Democratic Party.

Gazette reporter, Ian MacKenzie, remembered Douglas’s 1962 speech at Dalhousie as funny, charismatic, and that he was greatly concerned with the threat of nuclear weapons.

Douglas encouraged students to be wary of any government, stating they should spend money on defense as “there is no defense in a nuclear attack.” He was quoted saying, “We are living in a new age in which man has brought the atom under his control.”

While Douglas’ warning to students was timely, the main cover story was about the proposed trial-run of having no Christmas exams; instead exams were to be given during lecture time and the semester extended by two weeks to accommodate.

No matter the era, exam period changes were of the most importance to students.

During that same year, the Gazette would cover Dalhousie students running in candidate nominations for all three major political parties: the Progressive Conservatives, the Liberals, and the NDP.

In 1963, the Gazette paid tribute to former American President John F. Kennedy in their December issue. On the Dal campus, three-hundred students sat in the “Physics Theatre” and attended a commemoration lead by Professor Aitcheson, Dean of Political Science, and Professor Braybrooke.

The Gazette reported that students took part in a moment of silence and listened to an account of memories that both professors had of the president that emphasized his character. More coverage show students wonder of what would be the consequences of the president’s death.

The students concern was met with the political science professors trying to answer their questions to the best of their abilities. Students worried about Krushchev or the Communists, and were reassured by both professors that Johnson was an experienced politician and both Germany and the USSR would likely “tread lightly” rather than make a move.

Despite a Letter to the Editor, in the Gazette’s Dec. 4 issue of 1963, in which a Ronald E. Schaud writes, “we Canadians have not yet been annexed to the United States,” in response to the editor’s editorial the week prior on JFK’s assassination, the overall recorded reaction of Dal students during this event was that of sorrow.

By 1966, Dal students had spent six years picketing the student bookstore and eating locations on campus for the creation of a SUB. The cover story for the Gazette’s Sept. 29, 1966 issue was that Dal had agreed to a $3-million deal to finally build the SUB.

“The building will be five-stories tall, with a total area of about 112,000 square feet, and will be located on the south side of University Avenue between LeMarchant and Seymour Streets.”

“Dr. Henry D. Hicks, president of the university, said that although the plans of the building had not been given final approval by the board, it was expected that the construction would begin early next year. The official opening would be in the fall of 1968.”

Originally, the SUB had a games room and lockers in the basement where the bookstore is now. There was a kitchen designed to serve a cafeteria on the second level, currently the level that holds Pete’s-To-Go and Tim Hortons.

The third floor was designed to be a conference room that could hold 1200 people and council chambers, which is still true in 2017.

The fourth floor housed the offices of student societies, such as the Dalhousie Gazette.

Sub: Student Activism

The creation of a Student Union Building, while commonplace in the modern era, was an example of successful student activism in 1966.

Student activism on campus was organized through the student body rather than the Dal Student Union itself, and included large movements through marches.

In 1968, over one thousand Dalhousie students marched on the provincial legislature in support of National Student Day.

Tim Foley, Gazette News Editor, reported that students marched to demand the government to freeze residence fees, give a $300 bursary to all Nova Scotian students starting university, and higher wages for high school teachers among others listed in a brief presented by the Nova Scotia University Students; the march ended with the presentation of the researched brief on what they expected, and their recommendations on how the government could meet their expectations.

“Those of us who are now studying at universities are obviously not affected by financial barriers. They are not our problem so as much as they are the public’s problem. Yet as citizens of Nova Scotia it is our responsibility to communicate our analysis of this situation both to our government and to the public. It is through this letter, our march, and the public media, that we hope to do this,” stated the letter signed by Kim. S. Cameron, President of NSUS on behalf of eight “Member Institutions.”

The end of the decade also saw the Gazette publish articles tackling the issue of race.

In 1968, student activism increasingly became concerned with racism in Canada; the Gazette promoted the Black Power conference in Montreal that featured speakers who were members of the Congress of Black Writers.

An editorial from the co-chairmen of the congress, Elder Thebaud and Rosie Douglas was published in the September 24, 1968 issue of the Dal Gazette.

“The most noticeable characteristic of modern white oppression has been its guilt-ridden conscience. Not content to confine its vicious pursuit of material riches to the level of physical conquest, it has always sought to justify its oppressive control over other races by resorting to arrogant claims of inherent superiority, and attempting to denigrate the cultural and historical achievements of the oppressed peoples.”

From the Dalhousie Gazette Archives.

The article asked for white university students to recognize the achievements of Black people, and stated that “for the first time in Canada, an attempt will be made to recall […] a history which we have been taught to forget.”

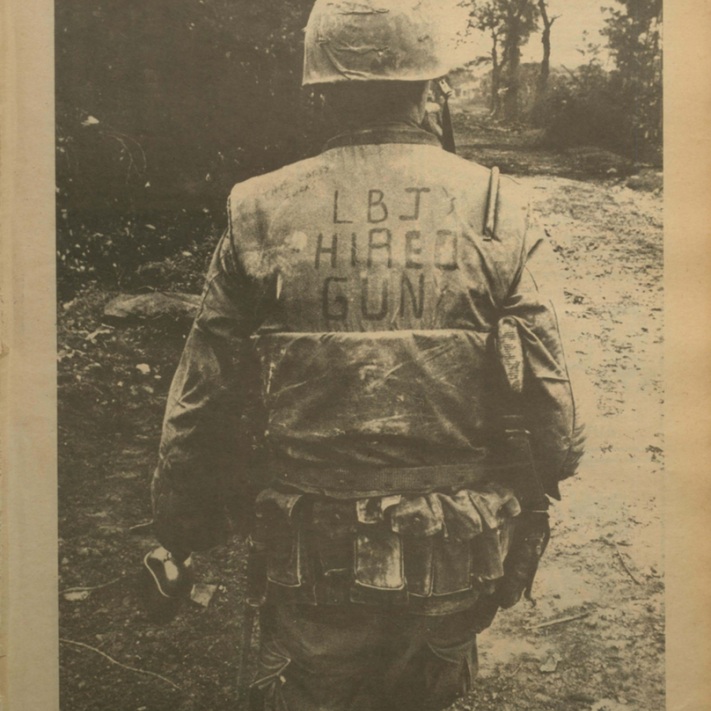

The end of 1968 saw Dalhousie students protest race relations in Canada, the ongoing Vietnam war, and their own student union.

By 1969, Dalhousie students were in an outraged state of mind over the lack of support for Black Power in Halifax, the lack of response from American President, Richard Nixon, to protesters against the Vietnam war, and the possible impeachment of DSU President, W. Bruce Gillis.

According to the Gazette’s Dec. 12, 1969 issue regarding the impeachment, Gillis had “abused the powers granted to him,” and the DSU had elected that the Dal student body should get to decide in a referendum vote if he should resign or not.

The commotion caused by students over the actions of Gillis caused the Commerce Rep to resign, and council members to turn against one another.

In what was a turbulent decade for Dalhousie, students were already well-practiced in their politics, and holding politicians accountable – even the student government variety – was not an opportunity the student body missed.