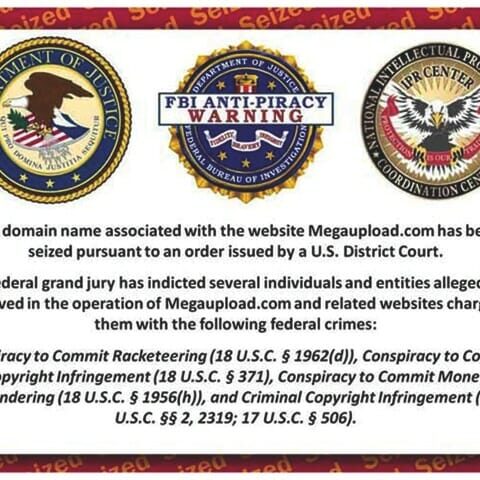

Megaupload goes bust

Hollywood producers love reminiscing about the days when people actually had to buy their product.

Hollywood producers love reminiscing about the days when people actually had to buy their product. In that sense, they are basically like old-school journalists with better suits. But while journalists cope by complaining about their fleeting jobs, people in the movie industry might have something going for them.

Hollywood producers love reminiscing about the days when people actually had to buy their product. In that sense, they are basically like old-school journalists with better suits. But while journalists cope by complaining about their fleeting jobs, people in the movie industry might have something going for them.

An increasingly involved government—of which the Jan. 21 shutdown of streaming website Megaupload.com seems to be a taste test—will entirely change how the movie and recording industries deal with copyright violators.

Just look at how those industries dealt with Napster about 10 years ago. When A&M Records wanted to challenge the peer-to-peer file-sharing service, they didn’t do it through a federal proxy. The artists and record labels filed lawsuits themselves and ultimately brought the company down through bankruptcy.

Napster received a court injunction after it was sued. However, this order was stayed and the company went through the civil court process. Even though the owners received the same government order afterward—that is, to keep better tabs on infringement occurring through their service–it happened after trial. In short, they were given the benefit of the doubt and due process, and therewith lost.

But things seem to be changing. Until recently, debate about the issue has revolved around the actions potential plaintiffs can take against those who threaten their revenues. In other words: How could those industries protect their intellectual property? How, and from whom, can they seek compensation?

A 2005 U.S. Supreme Court decision for the case MGM Studios, Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd. deemed that “one who distributes a device with the object of promoting its use to infringe copyright … is liable for the resulting acts of infringement by third parties.”

In Canada, a 2004 judgment by the Supreme Court of Canada found that Internet service providers can be held liable to pay royalties for cached copyrighted materials they do not remove, but only after they are given a reasonable chance to do so.

With both cases, the government’s role was simply to decide how the two parties could deal with each other and court injunctions against future business practices were made cautiously.

What happened with Megaupload may be a precursor to a significant shift in the government’s role. A U.S. federal prosecutor asked New Zealand officials to arrest the founder and head of Megaupload, Kim Dotcom, and raided his mansion in January. The Hong Kong Custom and Excise Department froze almost $40 million of the company’s assets. The case will not be between Megaupload and those claiming to have lost revenues; it will be a criminal trial.

The negative implications of this are quite obvious and have been said many times over. If the government can shut down a business in another country at the nudging of a third party, there is a large margin for abuse. If this becomes common procedure, there is nothing stopping corporations from trying to oust other corporations through the proxy of the federal government. While those arrested in the case may not be found guilty, their business has certainly been executed. Even though the idea of federal government complying freely with such attempts may be a slippery slope argument, one cannot deny that large business owners will try to benefit from even the slightest level of complicity. That alone should be concerning.

There is one benefit of a criminal trial. In a civil trial, both the plaintiff and defendant generally have an equal burden of proof. A tort claim (an accusation that one’s actions have caused personal harm or loss) such as copyright infringement requires a somewhat higher level of proof on the plaintiff’s part. Nevertheless, it is much less than the evidence needed to find a defendant guilty of criminal wrongdoing at a criminal trial.

The prosecution must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the accused is guilty of the specific crime(s) cited. Thus, if an accused copyright violator is brought to criminal court rather than civil, a more assured decision is likely—in theory.

The Megaupload founders might still face civil trials in their home countries thereafter, assuming they are not found guilty in the U.S.