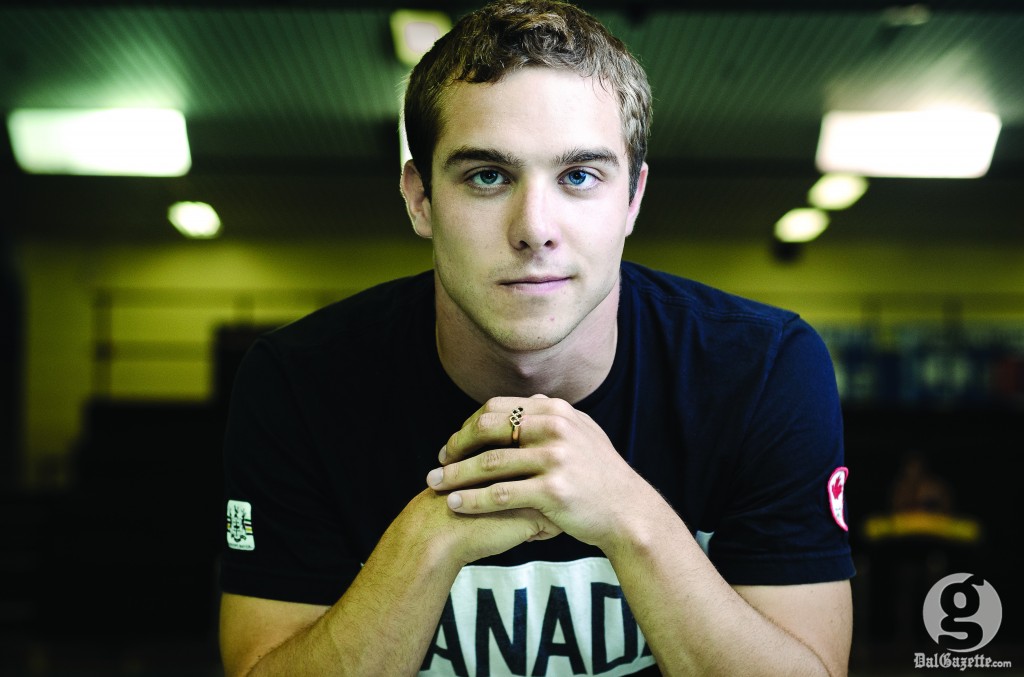

In Grade 1, David Sharpe decided that he wanted to be a swimmer.

He was already playing soccer and gymnastics but he soon turned his attention to swimming full-time, joining the Halifax Trojan Aquatic Club.

His mother, Helen Sharpe, remembers her son’s first race fondly.

“He must have been seven or something. He swam up to the other end of the pool, swam back and then asked the timer if that was all,” she recalls. “No, he had another left to do, so off he went and back he came,” she says, laughing. “I think he was like any young kid; he enjoyed doing it.”

He picked up the strokes very quickly and was identified at a young age as a butterfly specialist. He was even the novice winner of the swim-a-thon that first year.

Sharpe’s longtime friend and current Dalhousie teammate Chris Reith started swimming the same year as Sharpe. Little did he know a future Canadian Olympian was in his midst.

“He was always faster than everyone else in the group,” Reith says.

And he still is.

A swim to remember

Wednesday, March 28, 2012 is a day David Sharpe will never forget.

The 21-year-old varsity swimmer had spent months preparing for the Olympic trials. He only took one class in the winter semester to focus all his energy on swimming. He even visited other centres to train with the other top flyers in the country.

But after a poor showing in his heat, he was lucky to even qualify for the final at the Olympic trials.

“In the morning he missed his swim. He played around with [his technique] a little too much,” says Aaron Maszko, Sharpe’s coach.

The Dal student got over it, despite his underdog status. He was listed to swim in what is traditionally the slowest path, the eighth lane: a lane where swimmers are not expected to win.

But Sharpe is not like most people.

“When he sets a goal, he can do it,” says his mother.

Maszko agrees: “I don’t think there was a single Nova Scotian athlete that was there that wasn’t on the edge of their seat come the last length of the race.”

Sharpe came out of nowhere to swim the fastest 200 metre butterfly of his life, clocking in with a time of 1:58.81. He won.

“We were all delighted, just jumping up and down when he won that race,” says Sharpe’s mother.

Yet anyone watching the highlights at home would have never seen Sharpe touch the finish line. The camera operator seemingly did not expect Sharpe to win either, cutting out lane eight from the last shot, and in doing so cutting out history.

By winning the trials, Sharpe was technically nominated to the Canadian Olympic team (although the official team was only announced in June)—something no Nova Scotian male swimmer has ever done.

This is not insignificant. When Sharpe first decided to try out for the Olympics years ago, Maszko asked him if he wanted to go out of province. Training in Nova Scotia just wasn’t done.

“I think David likes to see himself as the first of many. He wants to be the role model that inspires others to go out and do this,” says Maszko. “Getting people to believe that it is possible is the biggest step towards having others achieve what he has done.”

Within a week of learning he made the team on June 29, Sharpe was in Montreal training with the Canadian team. He then stepped on an airplane to Sardinia, Italy for further training before heading to London in the middle of July.

“I probably learned more at the staging camp [in Sardinia] those two weeks than I have ever learned swimming-wise in any experience,” says Sharpe. “I was training with guys like Brent Hayden and Ryan Cochrane, guys who won medals; I was with them.”

Once at the athletes’ village, the goal was to establish a normal routine.

Eat, sleep, swim. Repeat.

To discipline themselves, the swim team skipped the opening ceremonies to rest.

“If you go, you go three hours early, stand up the whole time and get back at 2 a.m.,” says Sharpe. “It’s exhausting.”

Sharpe, however, watched the show from a big screen in the village with athletes from all over the world.

“As each individual country came out, people from that country would cheer,” he says with a smile.

Sharpe went to bed that evening only a few sleeps away from what he has spent months, even years, training for.

World’s biggest stage

Sharpe swam on July 30 at the London Aquatics Centre in front of 17,500 people. He says he has never heard a pool that loud.

“When I was in the ready room before my race I could hear the crowd rumble, because we were under the stands,” he says. “That was terrifying and exciting and exhilarating all at the same time.”

Although he was in second at the halfway mark of the 200 metre butterfly, Sharpe tumbled to a seventh place finish, ending an Olympics he was lucky to qualify for in the first place.

His swim was a full second slower than his trial time. Sharpe took a technical gamble with his stroke that did not work out.

“Through five-eights, almost three-quarters of the race, he looked very good, but in the last length he tightened up a bit more than he did before,” explains Maszko.

Reith, who was watching the race from home with his roommates at 6:15 a.m., thought Sharpe would break the Canadian record.

“He went out really fast in the race. We were all really excited about that and we thought it might be going down there, but next time it will happen,” Reith says.

“We still think he can break the Canadian record.”

That swim sets up Sharpe for an exciting future. His new goal is to not only qualify for the 2016 Olympics but to be in the top 20 internationally.

“I know it’s the starting point for what I have to do now,” he says. “That was the biggest event I could go to. Now, everything else is small potatoes, I guess.”

The full Olympic experience

After one minute and 59 seconds, Sharpe’s competition came to a close—but not his Olympic experience.

He saw other sports and met other athletes, explored London and went to parties.

“There was no alcohol in the village so most of the party was downtown,” he says. “When the party ends downtown, you go to meal hall and start again the next day.”

There were parties like the Speedo after-party, which Sharpe describes as the who’s who of swimming, from American swimmer Michael Phelps to Ryan Lochte. Invitations were only sent out to the British, American, Australian and Canadian teams.

“To have a plus one at that party, you needed to have a medal,” says Sharpe. “It was a great party.”

As the Olympics wound down, more and more athletes finally let loose. A record 150,000 condoms were given out.

All in all, Sharpe says it was a memorable time. “It’s a lot of fun,” he laughs. The smile on his face suggests we will never know just how much fun the Olympians had.

But the fun didn’t stop when Sharpe left London.

He was recognized at the airport—even without wearing any Olympic gear—and Reith says when they go out on the town in Halifax, people recognize Sharpe.

“The first night he got back we went to a bar and the band was like ‘Hey everyone, David Sharpe’s here,’” says Reith. “That was crazy.”

Back at Dal, Sharpe is trying to bring his life back to normal.

“Everybody asks, ‘How was the Olympics?”’ he says. “It was like a 45-day saga with months and years of preparation, and I have to sum it up? It was amazing. It changes how people look at you and how you look at yourself. It was life-changing.”

His friends and family notice some changes, but they still know Sharpe as the guy they play board games and video games with.

“I think he’s probably grown up a bit from this experience,” says his mother. “But his basic character seems to be about the same.”

Sharpe’s friend, Reith, sees the same guy he’s known for most of his life.

“He hasn’t gotten cocky or have a big head at all,” he says.

Sharpe even made time on his first day back from the Olympics to encourage the next generation of swimmers at a provincial tournament three hours away in Digby, N.S.

“All the kids were lining up for autographs. It really made their day,” says Reith. “It was a class act.”

Sharpe’s friends and family all agree: the swimming star has a newfound sense of focus and determination.

“He wants to be a major player and that’s really inspiring,” says Maszko. “When he talked to me after his race for the first time, he said it was great to go to the Olympics as a nobody, but next time he wants to be a somebody.”