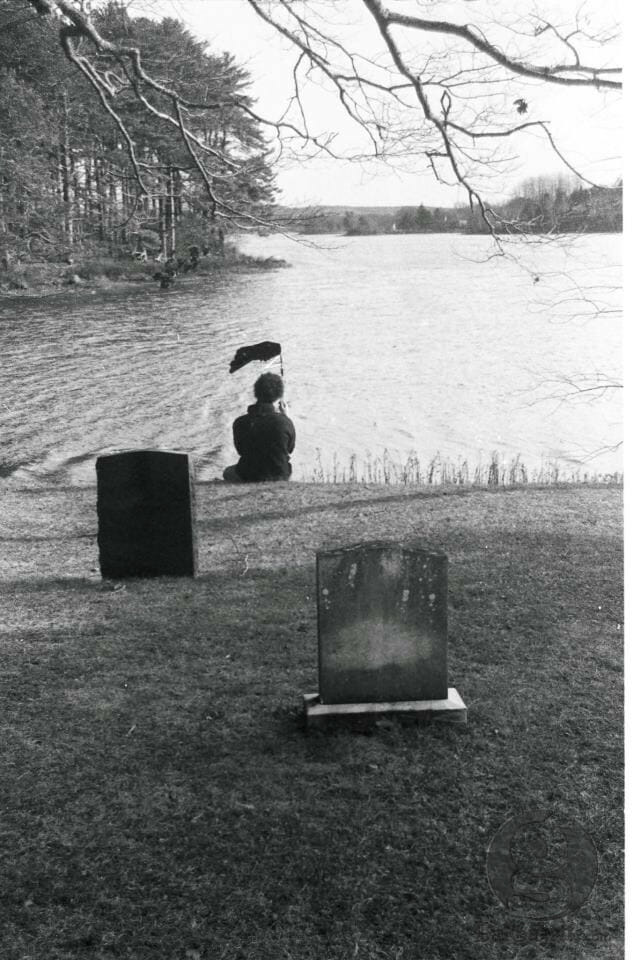

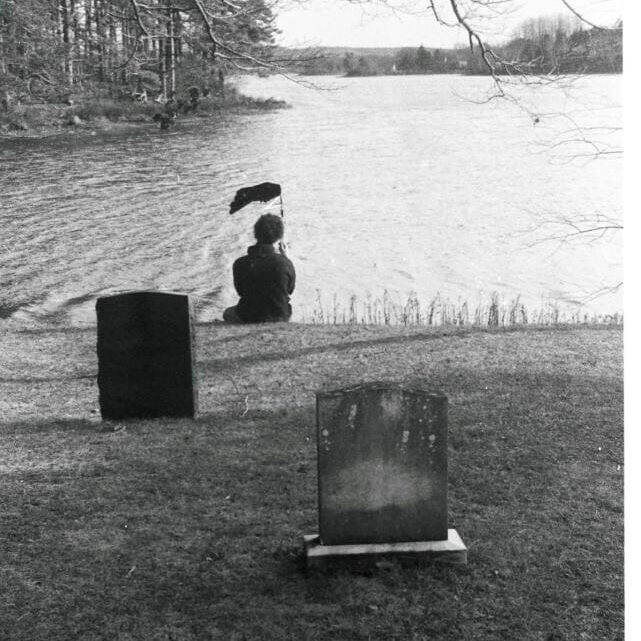

There is a wonderful, grainy solipsism in analog film. A warm blanket of black flecks, maudlin grey tones and softened skies.

We’re told digital is more lifelike, and it is in a way, but only in response to our rapid-firing, savagely shortened attention spans and ferociously fast-paced lives. We don’t have the time to coddle, treasure and develop that *one* archetypal image.

We need a hundred of them. In rapid succession. Oh, and we need them by noon, and then we’d like to edit out the flaws.

Now this might be an overarching and antagonistic statement, yes, but there is certainly no shortage of people who think their iPhone is a perfectly acceptable replacement for a nice, cumbersome and chromed-out 1970s Pentax.

Despite what all the talk about megapixels and shooting in raw will lead you to believe, analog film actually has a much richer detail and higher resolution than our current digital technology allows for. Negatives are also a direct copy of the image unfolding before us, a medieval-like trickery of light that captures a complete moment or situation. Digital photos are a binary code representation of life; they’re an approximation.

Don’t get me wrong, they’re getting very good at approximating, but there’s a reason that we refer to film as “analog” photography. True to the etymology, it’s a literal copy in every sense of the word.

Though, that’s not to discount digital. Digital cameras can deal with much higher speeds and sensitivities than film, and are much more desirable when there’s low light. They’re also clearly the best choice for super-speed sports photography or rapid-fire, rabble-rousing protest shots. Digital cameras are speed adjustable with a flick of a button; a film camera requires the choreful changing of the film to alter the speed.

A digital photograph is more of a slice-of-life document—at least, that’s what Daniel Rathers, a NSCAD student, tends to believe.

“Digital technology is more accessible now and plays a huge role in how people communicate. People have iPhones that have thousands of images on them and how people interact with those images is shaped by their immateriality,” he says.

To him, film is still a much more intuitive and expressive artistic medium than digital.

“Film is different in that it is tied to a physical object. It has a texture you can touch and chemical properties that can be unpredictable. I think it’s possible because of those attributes that you get to relinquish control in a way that you can’t with digital. This can change how we interpret the image.”

“I mean, I wouldn’t quote any of that though. It’s all boring shit. Ask Bryson, he probably has a good anecdote…” he says, meandering off the thought and on to a wine-soaked shoot in his kitchen.

But he’s got a point. Let’s be honest, your average flash-soaked two megabyte .jpeg is going to look like a jagged, washed-out piece of garbage next to a properly developed roll of film; critical moments and mummified time hang in a murky darkroom, immortalized in stoic black and white 8x10s.

Digital photography is well-suited for our agitated, anxious age of capturing every instant and documenting every dodgy hamburger we find in front of us, but it still has a long way to go.

There is a physical, immersive and almost mystical quality in film. You’re channeling a nostalgic evocation of the past with a memorable chunk of the present. There are textures and smells, bizarre lighting and chemical reactions and in some ways, it’s more an occult practice than an art form.

But I’ll be damned if I don’t love a broken umbrella in black and white.