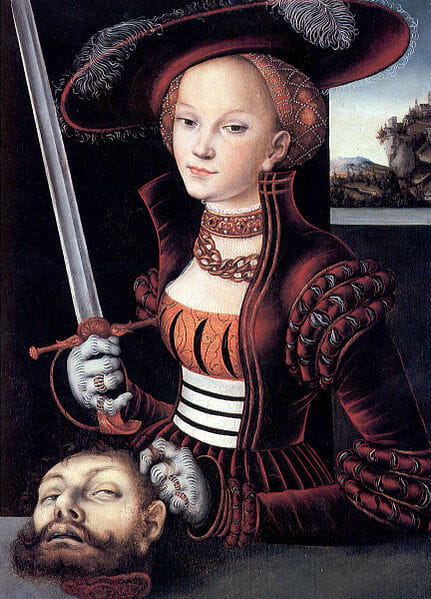

Judith mit dem Haupt des Holofernes, by Lucas Cranach the Elder. (Image taken from Wikimedia Commons)

Zoe Doucette

If you grow up as a girl, you are taught to fear from a young age. Fear becomes one of your best friends, because it is with you all the time, even when you’re not aware of it. Your body is objectified and reviled by your culture. You are taught not to display aggression. You are told that what you do, how you look, the fact of your very femaleness, may invite aggression. You should fear your presentation. You should fear your reactions, you should fear your own body. You come to watch yourself with nervousness. When you walk home at night, the smallest thing becomes a potential danger. Why is that car slowing beside you? What is that sound in the bushes? When someone warns you not to walk home alone at night, it seems absurd, because you are never really alone. Fear is always walking with you.

The genre of horror, as space for exploring social fears, has a special relationship with women. Women are often represented as the recipients and the originators of fear. Women are demons or victims. Often, they are objects of sadistic, sexualized violence. Sometimes, they perpetrate sadistic, sexualized violence. Sometimes, they get to be heroes. Feminist readings of horror are then incredibly relevant to understanding not only the genre of horror, but the way women are portrayed in film as a whole.

Read: Laura Mulvey’s 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure in Narrative Cinema”

This is a staple text of feminist film theory, which you will need to read as a starting point if you want to impress some hot feminists (of any gender/genderqueer persuasion) with your knowledge of horror at a vegan potluck or something. Mulvey’s psychoanalytic reading of the cinematic medium suggests that, by nature, the creation and viewing of film are constructed through a “male gaze.” Because of this gendered lens, representations of women in film and the experience of watching film provide the audience with scopophilic, or voyeuristic, pleasure. So what does this have to do with horror? If films and women in film are intended to provide voyeuristic pleasure to the audience, what kind of pleasure is the audience getting from the representations of women in horror cinema? How do the genders of characters perpetrating and receiving violence on the screen warp or conform to Mulvey’s theory of cinematic pleasure?

Watch: Rear Window (1954)

Not strictly a horror film, but Mulvey reads this Hitchcock film as a “metaphor for cinema,” where Jimmy Stewart’s Jefferies is the audience, and the apartment complex that he observes from his window is the screen. There’s a lot going on in this film, but Mulvey is specifically interested in the effect of voyeurism on the relationship of Jefferies and Lisa (Grace Kelly). When Lisa breaks into the apartment complex (crossing onto the screen, as it were), Mulvey sees her renewed as an object of voyeuristic pleasure for the audience. The fact that Jefferies is fascinated not only by eroticism, but suspected murder and violence witnessed through the window is equally of note.

Read: Men, Women, and Chainsaws, “Her Body, Himself: Gender in the Slasher Film” – Carol J. Clover (1987)

All of the essays in Carol J. Clover’s book Men, Women, and Chainsaws are worth checking out for fans of horror, but the seminal “Her Body, Himself,” which proposes the ‘”final girl,” is the most important. Clover wonders how the largely male audience of horror can relate to active female heroes if the cinematic gaze is truly as gendered as Mulvey proposes. Clover looks at the “final girl” trope within the slasher sub-genre and finds that, in horror cinema, there is some “bending of gender identification” going on. The final girl is “intelligent, watchful,” usually virginal, and the only character “developed in psychological detail.” Think Nancy in Nightmare on Elm Street, or Sigourney Weaver in Alien. The final girl, appropriating some suitably phallic weaponry, takes on aspects of the masculine, fighting to save her life, while the psychotic killer she wards off is often a neutered, feminized male. Horror film for Clover does not privilege the male view, but, by allowing cross-gendered identification, presents a complex, murky space for probing social anxieties about gender.

Watch: Halloween (1978)

The original Halloween‘s Laurie is one of the most clearly articulated examples of Clover’s final girl. Laurie (scream queen Jamie Lee Curtis), a wholesome Midwestern babysitter, faces hockey-mask-loving slasher Michael Myers on a sleepy Halloween night. Being bright, sweet and handy with an arsenal of weapons makes Laurie a classic final girl.

Dream Home (2010)

Frustrated young woman Lai-sheung (Josie Ho) takes on the traditionally male role of depraved slasher in this film about the cut-throat Hong Kong housing market. The cartoonish, slapstick ultra-violence, inventive kills (including suffocation by home vacuum-sealer), and strange plays on gender make this a great piece to watch as an accompaniment to Clover’s work.

Extra Credit:

Teeth (2007)

Teeth has all the subtlety of a jackhammer, but it’s a fun and sphincter-clenching look at traditional anxiety about women’s bodies.