What’s been going on at Dal??

Dal's latest national controversy blew the conversation of race wide open, now they're trying to figure out how to talk about it

Editor’s Note: Words are used to communicate specific ideas; a word is only useful to the extent that it‘s common meaning is understood by each person. In modern discourse, racism and racist are used to communicate a number of related but decidedly distinct ideas, so they‘ve become inefficient, if not totally counter-productive. Systemic racism or institutionalized racism refer to the structure of racism that can only affect marginalized people, and racially prejudiced refers to discrimination based on race, which, by definition, could be applied to all people.

On June 28, 2017, the Dalhousie Student Union (DSU) attempted to pass a motion in support of the struggles of Indigenous students on campus. The motion resolved the DSU to not partake, promote or celebrate Canada Day because it recognized the holiday as an act of colonialism. Although the motion was eventually overturned for procedural reasons, the DSU believed it was valid when they voted.

The response to the motion was swift – much of it negative.

On July 1, the DSU made a Facebook post explaining their stance regarding Canada 150. The vast majority of the comments on the post, from both current students and alumni, disagreed with the DSU’s position.

However, 95 people ‘liked’ the post, 55 responded with an ‘angry’ face, and 25 ‘loved’ it.

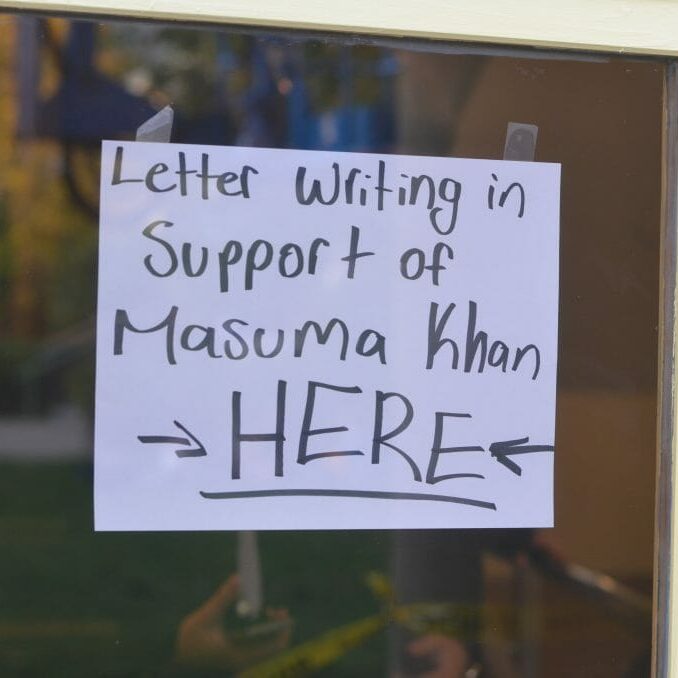

On top of the criticism the DSU received for its position, individual members also received personal attacks. Most notably, Masuma Khan, Vice President Academic and External of the DSU did; she’s the council member who introduced the original motion, and was subjected to a number of vitriolic private messages that focused on her as a person, and not the motion the DSU had passed.

Khan described the messages: “People trying to shame me for being Muslim; people trying to shame me for my opinion; people trying to shame me for being in this country, and shaming my identity and shaming every single part of me. Shaming my culture. Shaming every essence of myself.”

Aside from the issue of targeting someone’s entire being for a single idea that they hold, Khan was not even wholly responsible for the motion. She was the one who introduced it, and then the council as a whole discussed it, amended it and voted on it. The majority voted in favour.

“This motion wasn’t meant to just go by and pass like that. It was meant to be amended,” said Khan at the June 28th DSU council meeting.

White Fragility

On June 30, the Nova Scotia Young Progressive Conservatives made a Facebook post expressing their disappointment in the DSU’s motion to abstain from Canada Day celebrations, but it didn’t contain personal attacks against any members of the DSU executive.

Shortly after, Khan posted her now infamous Facebook status, which, as has been covered extensively, included the terms: “fuck you all,” “#whitefragilitycankissmyass,” and “#yourwhitetearsarentsacredthislandis.”

Khan said the main point of the status was explaining why she introduced the motion in the first place, and why it was important to support Indigenous people: they were still feeling the effects of centuries of colonialism and genocide, and that wasn’t something to be proud of.

What’s more, Khan says her post was not meant to be seen by the people who disagreed with her as much as it was a message to her personal friends on Facebook – she was feeling invalidated and frustrated with all of the personal attacks she was receiving, on top of the backlash to the motion itself.

There’s been a lot of discussion about whether Khan’s comments were racially prejudiced; many people interpreted “fuck you all” to be directed at white people in general, not just the people who’d been sending Khan personal messages.

But another component of the status that people interpreted as racially prejudiced was the term white fragility.

White fragility was coined in 2011 by Robin DiAngelo, who has a PhD in multicultural education. As a relatively new phrase, it’s often misused and misunderstood.

Fragility isn’t uniquely inherent to white people. But in this case, the term refers to a whole class of responses that a large group of people has in common.

When white people are called out on their actions they may respond defensively, not understanding how their actions could be viewed as racist. It’s the same way any person reacts to criticism that they deem unfair or unwarranted – borne of the same psychological mechanisms that all humans share.

White fragility is human fragility manifesting itself in white people because our society’s structure is built on white people historically (and presently) holding a disproportionate amount of power. White people are generally unaware of the near-ubiquitous systemic racism that affects marginalized people, and so act in ways that unintentionally compound this systemic racism.

White fragility is as real of an observable phenomena – and the by-product of societal circumstances – the same way a disproportionate number of African Canadians living below the poverty line in Canada is.

Formal Complaint

Khan intended for her status to be a personal declaration of defiance to the people who were attacking her, meant only for her Facebook friends to see. However, she did make the status public, and she did use ambiguous language that could have been – and was – interpreted as being demeaning or even racially prejudiced towards her Dal peers, the very people she was voted to represent.

Michael Smith, a graduate student in the history department read Christie Blatchford’s article about the DSU motion in the National Post, which led him to Khan’s Facebook profile that had her notorious status at the top. Smith filed a formal complaint against Khan followed by an opinion piece of his own in the National Post.

In an email sent to the Dalhousie Gazette, Smith wrote he believed Khan’s post was “racist, discriminatory, and unwelcome,” and that “nobody attacked Khan. Khan attacked the majority of people on campus,” apparently unaware of the number of hateful messages that she had been receiving in the lead up to her Facebook post.

How would he have expected Khan to respond if he’d known about the multitude of verbal attacks that had been levied against her, considering that a single Facebook post on Khan’s personal account led to “tears at hearing someone curse [him] for the colour of [his] skin,” and writing an opinion piece that called out Khan by name in a national newspaper?

Khan learned of the complaints lodged against her by Arig al Shaibah, the university’s Vice-Provost of Student Affairs, who is responsible for handling these types of complaints against students; Al Shaibah said she received a number against Khan.

“Not just [from] white identifying students, but students with diverse backgrounds had expressed that the language and the tone and the tenor felt demeaning and disrespectful and derogatory to them, and had them feel unwelcome and unincluded and somewhat feeling intimidated given it was coming from a student leader at the university,” she said.

Al Shaibah met with Khan a few times in July to discuss the complaints filed against her, at which point Khan sought legal counsel.

Around the same time, on July 19, the Canada Day motion was again presented at a DSU council meeting – this time following proper procedural rules.

The version passed in this meeting was heavily amended from the version passed on June 28. In the July 19 motion, the DSU resolved only to “partake in Canada 150 by offering alternative programming that explores marginalized perspectives in consultation with those communities.”

Saga isn’t over

Sometime in August, al Shaibah offered Khan an informal resolution to the complaints lodged against her: attend educational workshops about having respectful discourse. Khan refused that informal resolution – as is her right, al Shaibah said.

“But the code as written, once you engage it, it kind of follows these steps and if informal isn’t accepted by all parties… then it kind of is a domino effect and it goes on to the Senate Disciplinary Committee,” she said.

The Senate Disciplinary Committee’s job would have been to determine whether Khan’s post did in fact contravene the Code of Student Conduct.

Al Shaibah was in an unenviable position.

As a woman of colour with a Muslim upbringing, al Shaibah says she empathized with Khan’s experiences; she also felt personally and professionally obliged to empathize with the students who felt demeaned by Khan’s post.

Khan was greatly disappointed that al Shaibah accepted complaints that Khan says were racially charged or derogatory. Khan feels that the school was choosing to elevate those voices above her own.

“[Smith’s] complaint is filled with racist remarks. His complaint says ‘Masuma Khan, who is ironically an immigrant…’ [Khan was born down the road from Dalhousie.] Like, my university accepted this complaint about me,” Kahn said.

She says that if al Shaibah was really empathizing with her, she shouldn’t have automatically accepted the complaints with their racially motivated language – which did not have anything to do with Khan’s Facebook post. She also thinks al Shaibah should have been more understanding of the frame of mind Khan was in when she made the post in question, considering Khan and her counsel had shown al Shaibah the kinds of hateful messages she had been receiving leading up to it.

For her part, al Shaibah didn’t feel it was her place to police Dalhousie students’ responses to Khan’s post or tell them their emotional reaction was invalid.

Code of Student Conduct

Al Shaibah originally considered whether Khan’s post violated two separate sections of the code:

C.1.(e) which states students shall not discriminate or harass people based on their race (among many other things,)

and C.1.(f) which states students shall not engage in conduct they know or ought to know would cause people “to feel demeaned, intimidated or harassed.”

Al Shaibah determined that there wasn’t reasonable evidence to progress the complaint based on racial prejudice, but that Khan did conduct herself in a way that contravened the latter section.

“It’s not necessarily the substance of what [Khan was] attempting to say but more the manner of expression that could have people feeling demeaned and disrespected,” said al Shaibah.

Al Shaibah also hoped that the Senate Disciplinary Committee would find that Khan should attend the educational workshops that had been offered to her as an informal resolution; that was the only outcome that was realistically on the table – never suspension. Never expulsion.

Khan is a member of the Senate Disciplinary Committee, but was suspended from her duties while her case was under review. She said the time she spent waiting for her case to progress to the committee was time she wasn’t able to advocate for the students who needed her, which she was almost uniquely able to accomplish as one of the few minorities on the committee.

Eventually, Khan and her legal team became tired of waiting – they took her story to the media.

What Comes Next?

The public at large became aware of the case and details about the process leaked out. The resulting reaction included national backlash against Dalhousie’s handling of Khan’s case and even more hateful messages directed at Khan from people across Canada.

In light of the controversy surrounding the case and the various issues it was raising, al Shaibah decided to withdraw the complaint against Khan for three main reasons, as outlined in her memo to the school:

- the events surrounding Khan’s case made al Shaibah doubt the ability of the code to properly balance a student’s right to free speech with students’ right to access campus life unimpeded

- Al Shaibah thought pursuing educational outcomes outside of the senate disciplinary context deserved more thorough consideration

- the hateful and polarized behaviour and discourse the situation caused was undermining the very values the discipline process was intended to uphold.

Al Shaibah says she only ever wanted the community to come together in a respectful dialogue; it was one of the main motivations in her offer of educational workshops to Khan as part of an informal resolution. When the dialogue surrounding the case fractured the community instead, al Shaibah decided it was counter-productive to continue the process.

In the clear – not over

Al Shaibah made it clear: Khan is officially in the clear, but al Shaibah doesn’t condone Khan’s message and isn’t backtracking on her initial interpretation of the Facebook post as potentially harmful. But the other considerations outweighed the value in progressing with Khan’s case.

Al Shaibah said that the complainants “were agreeable with the broader principles and bigger principles of having conversations and dialogue” when she informed them she was withdrawing the complaint.

Even though the complaint is withdrawn, Khan is not satisfied. She believes the situation should never have gotten to the point where she felt compelled to go public.

“I think people also have to understand that I’m my own human being, and I also have certain experiences that I live; and that I can’t separate the effects of oppression from my day-to-day life. I face it on the daily. I understand that some students were hurt by that message. I can only say that I didn’t mean it in that way,” she said.

“That was a moment of such frustration, I just couldn’t deal with that oppressive system anymore, and I had to speak out about it. I had to express myself. Why isn’t that folks aren’t understanding that this is the way that I need to survive? I need to be validated for my feelings. I also have to exist in this world too, and these are my realities.”