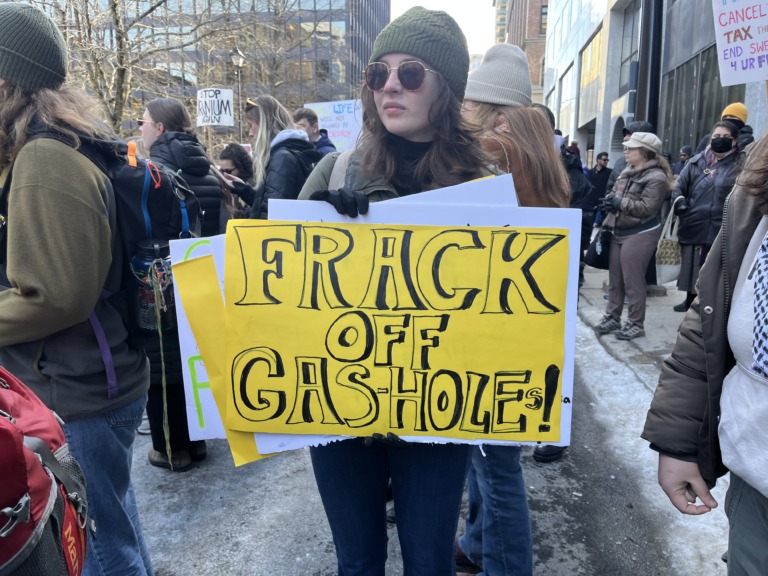

- Should we disappear under the deluge of information, or risk the implications of personalized results on the internet? (Photo by Josh Fraser)

Have you tried hunting for information about Ukraine lately? As with any hot topic, the internet has positively exploded on the subject, with dozens of news sites publishing page after page of reactions, analyses, and predictions. While I browsed, I wondered how difficult it is to see the big picture amid the endless clicks and scrolling.

More than ever, I consider the internet problematic. Not only has its temporary status as the ‘information superhighway’ been debunked, but it has begun to contribute to the unease and confusion infecting the world. Basically, I’m fed up with the inundation. I open my browser and feel buried under the sheer number of words I’ll have to process, even if I’m just scanning.

Companies like Google and Facebook have caught on to this overwhelming feeling among customers, and have come up with several manoeuvres to wrap a warm, fuzzy blanket around users. One key feature of so-called ‘personalisation’ is the tailoring of search results based on user activity. For instance, you get slightly different search results on Google if you’re signed in to your own account, where your search history (stored at Google, not on your browser) is used to help you find what the engine thinks you are looking for. Facebook news feeds present ads using similar principles, and the feed itself is mediated by the people you interact with the most.

There’s probably some really clever code in there, and some sound logic on customer service. But as Eli Pariser explained in a 2011 TED talk, what is happening as the internet is mined for consumer activity is the development of what he calls ‘Filter Bubbles.’ In a nutshell, consumerism has turned the net into a feedback loop for many users.

The internet, like every major communication technology, is owned by advertising dollars. When we go online (assuming one is ever ‘offline’), the goal of every site turned up in a search engine is to attract and entertain. Journalism has been made to conform, and has suffered for it. The internet is simply not designed to provide accurate information. Its nature as an instantaneous medium can pressure journalists to publish unedited drafts for the public because exclusivity is extremely important in the industry. The editing process happens invisibly. Changes are not recorded, most of the traffic has long since moved on and there are few options for retraction once something is set loose online. Furthermore, the aura of the internet gives an impression of global reach, and the biases of culture and geography are distorted instead of noted.

The internet has no privilege; it is a new technology we are grappling with as a species, and we should be asking ourselves how much control we have as free agents if we depend too much on it. If we rely on typing, servers and electricity to relate, something as simple as power outages turn quickly from inconveniences to crises. It’s not certain—but the potential hangs above us like an anvil.