The possibility of a seven billionth person raises a red flag

On Oct. 31, the global population surpassed seven billion people (well, plus or minus 56 million people). The United Nations census estimates a one to two per cent margin of error in the calculation, which comes out to approximately 56 million people when you’re talking about a global population of seven billion. The margin of error is so large that the birth in question could have happened in August of this year, or the baby might not even have been conceived yet.

No one really knows when or where number seven billion will be—or was—born, but we do know the miscalculations come from many of the world’s poorer nations that have extremely inaccurate demographic birth and death records.

At a press conference on Oct. 31 at the UN headquarters in New York, Secretary General Ban Ki-moon stated, “Today, we welcome baby seven billion. In doing so we must recognize our moral and pragmatic obligation to do the right thing for him, or for her.” The secretary general stated that in 1998 the world’s population was at six billion, and that according to the UN, the global population is expected to grow to nine billion by 2050. That’s a huge number. How are we supposed to sustain a population of seven billion, let alone nine billion people in less than half a century?

What we do know is that since the 1960s—when the global population was three billion—the world population has expanded at an exponential rate,

By 2100 there will possibly be 50 per cent more people on earth than there were at the beginning of the century, all vying for the same resources.

In a finite world where population growth is exponential as opposed to logistic, the per capita share of the world’s goods must steadily increase in order to provide sufficient resources to all living species. Since our planet can only support a finite population, it is inevitable that at some point population growth will equal zero.

So how do we support a growing population from exhausting the world’s resources? Do we stop having babies or impose regulations similar to the Chinese one child limit in the 1990s?

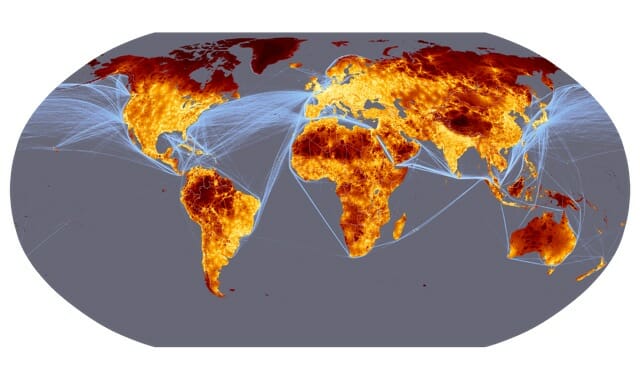

Educating women in underdeveloped countries has been a proposed solution by numerous scholars, becoming a widely accepted methodology in mitigating our current population crisis. The world’s population is distributed asymmetrically across the seven continents, with most of the population growth stemming from less developed countries. Asia, the most populated continent on Earth, is home to over four billion people and a whopping 60 per cent of the total global population. So what exactly does this mean for women?

In most developing (or third world) countries, access to any sort of contraception is extremely difficult. Not only do these women have a minimal amount of time between pregnancies due to lack of contraception, they are unable to deliver children into a safe and healthy environment. Focusing on education for women in many of the poorer nations is an essential piece to solving our global population problem. By spending more time in the classroom educating the global population, we’ll have a better chance of lessening the population crisis.

Even though there is no clear solution to our population growth problem, the long-term maintenance and management of the resources on our planet for future generations is a task of utmost importance for those of us alive today. Based on our current trends, it is almost naive not to acknowledge that the relationship with our planet between population growth and the production of finite resources must change. We have already “surpassed” the seven billion people marker, so if change is going to happen, it has to be soon.

It’s our obligation to the seven billionth person, wherever or whenever they may be born.