SuddenlyLISTEN improvisational collective gets a little Wilde

The Picture of Dorian Gray: Revised

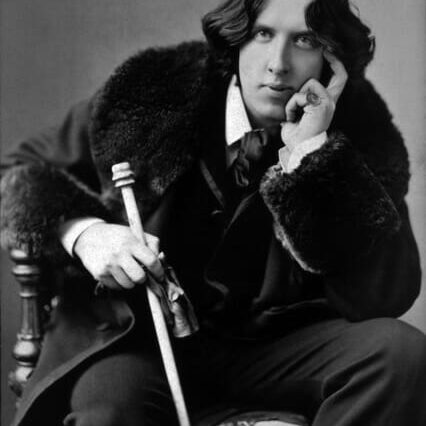

Dorian is an engaging, enigmatic combination of improvisational acting and music, and an avante-garde revision of Oscar Wilde’s classic The Picture of Dorian Gray, that sees improvisational musicians performing alongside improvisational actors.

Norman Adams, the creative force behind the SuddenlyLISTEN improvisational collective elaborates. “We don’t want the music just soundtracking the acting, but we also don’t want the music at the forefront. We’re trying for this perpetual ‘tug and pull’ narrative style, playing off the themes of the book, not just reading it on stage with music.”

Opening night was a glum, grey Tuesday, and yet the Bus Stop Theatre was washed in an electric haze of vibrant chatter, a slowly boiling mix of anxiety and excitement. Once the fibrous floods of onlookers had swarmed into the tiny theatre, cramming their waxing and waning frenetic pulses into the chairs, the room began seething in a frenzied dirge of dirty bass and backhanded cello. Staunch and dysphoric, a ravaging, relentless low end buzz clawed through the delicate, pixilated hush as Dorian began.

Tense initial words seemed to tug and shake the music, in turn flooding the actors’ intonations and annunciations with a drifting, melodic quiver. The creaking, haunting sobs of Gina Burgess’ violin sway aimlessly around David Christensen’s staccato stabbing flute, sliding ever slightly out of the grasp of Adams’ cello, and the massive rumbling void of Lukas Pearse’s thundering double bass.

Carreening around each other and into a ritualistic klesmer cling/clang of “take the lead,” actors Theo Pitsiavas and Sebastien Labelle swill white wine and mumble purposely inaudible conversation as they swirl around the audience, eventually settling into seats and sliding—slightly—through the fourth wall as they make crass comments and strike up conversation with the patrons.

Emphasizing the platonic love of the play, they slide across the studio and drawing room, drawing back the blinds, captivating the crowd as Gina Burgess appears as the horrifically immaculate portrait, serenading us with sweet, sweeping violin bows and sending shudders through the room.

As the musicians take to playing Victorian glassware, the actors tucked in shadows, the audience breaks out in a fit of ill-placed, oddly-timed laughter. As if taking it for a cue, the scene degrades into a swath of opium den debauchery, bubbling pipes and stoned laughter mirrored back at the baffled audience. Actor Karen Basset steps out of the dark and to the front of the stage, bends down and grabs a sealed envelope. As she tears it open, she smirks and nods to the musicians as they coalesce in a hybrid solliloquy of an Oscar Wilde quote, one of several throughout the performance.

“It is the spectator, not life, that art really mirrors” she says with a diabolical smirk to the tune of Adams’ schizophrenic cello screeches.

The portrait then returns, worn and wicked, crooning a different tune as Dorian recoils in a wash of bass driven horror, red lights trickling in razor sharp patterns on the stage. Gina Burgess is an effigy, reflecting the solipsistic, savage deterioration back at Dorian in a sick and deceptively beautiful melody, moonlighting as the antagonist.

The devilish portrait’s realization is spilling into a rabid swarm of vermillion bathed fear, as Lukas Pearse is now the thundering force behind the sheet of white, drudging on demonically with pulsing, grumbling bass tones. In a dreadfully self-reflective gloss of post-modern rhetoric and a implicit refrain of “The spectator, not life, is what art really mirrors,” Dorian runs screaming from his abomination; a modern mock-up, writhing agony of self-existence in vain, envious representation of your own appearance.